Chris Lloyd went to Barnard Castle in search of fire plates and stumbled across a blue plaque that flew him to the moon.

ON the moon is a crater called Murchison. In New Zealand is a town called Murchison, as there is in Australia. In Antarctica, there is a Mount Murchison, as there is in British Columbia, Canada, where there is also a Murchison Island. In Uganda, on the River Nile, there are the Murchison Falls and, in Western Australia, there is the Murchison River which has two tributaries: the Roderick River and the Impey River. And in Barnard Castle, there is a grand house with a blue plaque which says that Sir Roderick Impey Murchison lived here.

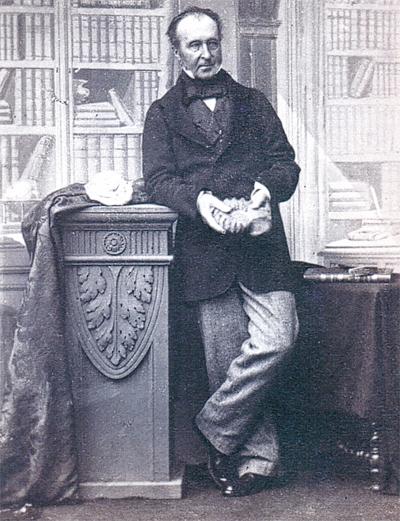

SIR Roderick was the Professor Brian Cox of his day: the most famous scientist in the country.

He started out in life as a wealthy Scottish soldier, who was on the cusp of dissipating his life away, when he fell in love with a girl with Barnard Castle connections who introduced him to the joys of science.

With the ears of monarchs, tsars and prime ministers, he toured the world, studying rocks, pushing back the frontiers of knowledge and proving that the British Empire could be a force for progress.

“Sir Roderick was as faithful a servant of his scientific mistress as he had been of his king,” said The Northern Echo after his death in October 1871.

“The same valour which had borne him across the blood-dyed battlefields of Spain, the same heroic courage which nerved his arm as he bore the standard and charged at the head of his troops in Corunna actuated him in his geological researches.

“He travelled all over Europe in search of information.

Wherever there was a mountain, there, drawn by a powerful attraction, was Sir Roderick.

“Untiring in energy, undaunted in perseverance, he allowed no difficulty to impede, nor danger to warn, him from the path he had determined to pursue.

“Careful in calculations, cautious in his deductions, comprehensive in his survey, he was an honour to the science which he illustrated, and the country which gave him birth.”

That country was Scotland although, aged seven in 1799, he was sent from Ross-shire to grammar school in Durham City.

Threatening to tumble off the rails, he was forwarded to military college at Great Marlow, in Buckinghamshire, aged 15, and he was fighting in Spain two years later.

His military career was not as glorious as the Echo’s obituary suggested – Corunna was a disastrous retreat – and he retired from the Army in 1815 having just married Charlotte, the daughter of General Francis Hugonin of Kent. Still only 23, Murchison was spending wildly beyond his means and thought of no more than the next fox hunt.

Luckily, Charlotte had just inherited her grandfather’s house in Galgate, Barnard Castle, and the newlyweds moved in.

Charlotte – a sensible, educated girl with her own scientific bent – was as wily as any fox. She took Murchison on a grand tour of Europe’s galleries and museums, and she introduced him to the gentry of Teesdale.

He became close friends with Harry Witham, of Lartington Hall – in whose memory the Witham Hall was built – and JBS Morritt, of Rokeby Park. Morritt was an amateur scientist who took him on field trips up the dale and, in 1823 at Rokeby, introduced him to Sir Humphrey Davy, the famous chemist who invented the miners’ Davy lamp.

This was the clincher. Encouraged by Sir Humphrey, Murchison decided to pursue science instead of the fox and, inspired by the rocky nature of Teesdale, threw himself into the new science of geology.

Usually accompanied by Charlotte, he toured Britain, and then crossed the Alps to study Russian rocks. In 1839, he published his greatest work, the Silurian system, which for the first time classified the strata of rocks.

That same year, Charlotte inherited an even grander mansion in Belgrave Square, London, and their connection with Barnard Castle – certainly as residents – seems to have come to an end.

MURCHISON rose. In 1843, he became president of the Royal Geographical Society and, in 1846, he was knighted by Sir Robert Peel.

For 20 years, he directed British scientific expeditions around the growing Empire, preaching about the intellectual importance of imperialism and even urging ministers to seize various countries so he could send a mission out to investigate their rocks.

Without him, Victorian knowledge would have been much poorer and, such was his pre-eminence, if there had been a television programme explaining the creation of the planet, he would have hosted it.

Instead, he had to content himself with the media of his day – speeches and books and newspapers – in which he made much of his geological prediction in 1844 that gold would be found in Australia.

In 1851 when it was, he basked in the glory, forgetting to mention that he was right for the wrong reasons.

No scientist of his day – not even his close friend, the explorer David Livingstone – received more honours from more countries than Murchison, and his entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography concludes: “The earth sciences in Britain have never had a more dedicated and effective promoter.”

And this man, who has more than 20 features across the universe named after him, began his rocky climb to the top in Barnard Castle.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here