Redcar is to lose its biggest employer and one of the largest manufacturing plants left in Britain. Echo Memories steels itself for what the future holds

"THE iron of Eston has diffused itself all over the world.

It furnishes the railways of the world; it runs by Neapolitan and Papal dungeons; it startles the bandit in his haunt in Cicilia; it crosses over the plains of Africa; it stretches over the plains of India. It has crept out of the Cleveland Hills where it has slept since Roman days, and now like a strong and invincible serpent, it coils itself around the world.”

For 160 years, steel from the Tees has wound its way around the globe, building bridges, railways and the foundations of empire.

But next month, with the “mothballing” of the Corus plant near Redcar, the industry which once employed 33,000 will be down to its last handful of hundred, and the Steel River will be reduced to a puddle.

Man had known that there was ironstone in the Cleveland Hills since the 12th Century.

Dotted across the Yorkshire Moors is evidence of early bloomeries – the primitive furnaces used for melting the iron out of the stone.

But the landowners of Cleveland – “the land of cliffs”

– believed that their ironstone was too poor quality and too remote to be useful on an industrial scale.

And so the large, flat saltplains at the foot of the cliffs were left to farmers, disturbed only by pilgrims who stopped on their journey between the two great Christian centres of Whitby and Durham. In fact, the pilgrims may have had an overnight cell at the midpoint and so they would say they had stopped at “Mydilsburgh”.

All this tranquillity disappeared on August 18, 1828, when Joseph Pease, of Darlington, sailed into the mouth of the River Tees and imagined a bustling seaport before him on the saltplains. He bought 520 acres, hung the world’s first railway suspension bridge over the river and drove his Stockton and Darlington Railway (S&DR) into Middlesbrough.

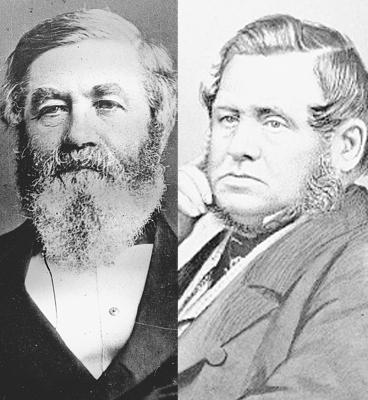

Joseph needed other industrialists to help him make his acres profitable, and in 1840 he offered some cheap riverside land, “a dreary waste of mud on which sailors had discharged their ballast”, to Henry Bolckow and John Vaughan.

BOLCKOW hailed from northern Germany, but had been dealing in grain on Newcastle’s Quayside for more than a decade, amassing a £50,000 fortune (£3.8m in today’s prices).

Vaughan, a Welshman, had been in iron all his life, and was working in the trade on Newcastle Quayside. He had the brains; Bolckow had the money. They married sisters, and moved to Middlesbrough.

Seeing that railways were the future, they opened a foundry on their dreary bit of mud.

But they had their logistics all wrong. They shipped ironstone from Grosmont, near Whitby, to Middlesbrough where they loaded it into empty coal wagons and sent it along the S&DR to Witton Park, near Bishop Auckland.

In Witton Park, they had blast furnaces, fired by local coal, which created pig-iron. They loaded the iron back onto the railway and returned it to Middlesbrough to be rolled into bars in the foundry.

Too much to-ing and fro-ing to make sound financial sense.

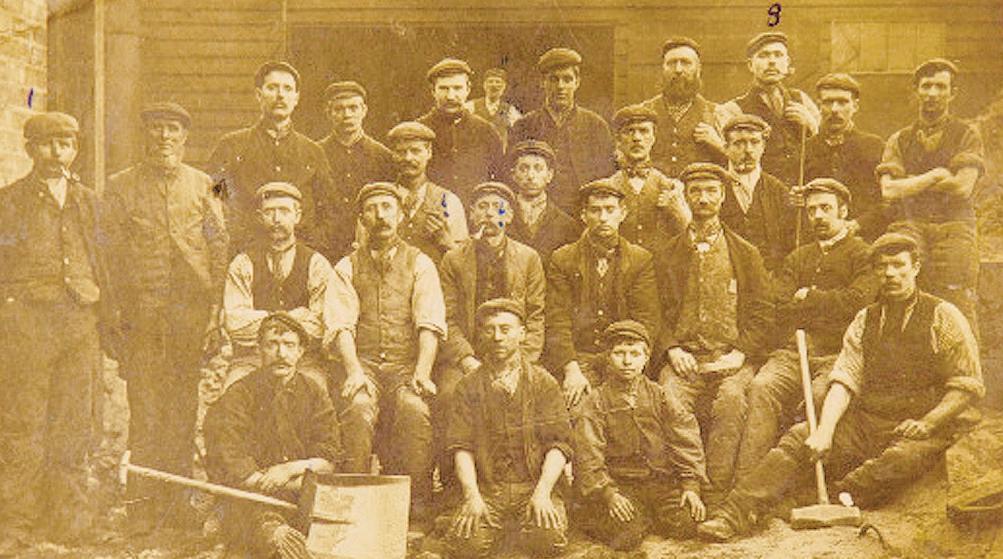

One of the collieries that Bolckow and Vaughan opened in 1846 to feed the Witton Park furnaces was Woodifield, near Crook. The engineer was John Marley, who came from Middridge Grange near Shildon.

He became friendly with John Vaughan.

Legend has it that on June 8, 1850, the two men were out shooting rabbits in the Cleveland Hills. Marley tripped over a burrow. As he sprawled down the hole, his hand landed on the purest ironstone he had ever seen. “Eureka!” he shouted.

This does the men a disservice.

At Vaughan’s instigation, Marley had studied Cleveland’s geology in the search for the Holy Grail of a seam of rich ironstone. Having developed a theory on paper, they walked into the hills that day and were immediately proved right: a 16ft thick layer.

“Having found this bed, we had no difficulty in following the outcrop west without any boring, as rabbit and foxholes were plentiful,” wrote Marley, setting off the rabbit legend.

Still, it was a eureka moment.

They had found it.

On August 13, they started mining at “Bold Venture”. On August 17, they started laying a tramway to the mouth of the mine.

On September 2, the first seven tons of limestone came out of the mine, down the tramway, onto the railway and up to the Witton Park furnace.

There it was pronounced good.

The ironrush began. Men dashed to Middlesbrough dreaming of making a fortune.

There was iron in them thar Cleveland Hills. It must have felt exactly like the gold rushes of California (1849) and Victoria, Australia (1851).

Bolckow and Vaughan were first off the mark. They opened their Eston ironworks in 1852.

JOSEPH PEASE wasn’t far behind. He was greatly assisted by owning a railway. The other railway board members dismissed his plans to build a line from Middlesbrough to Guisborough, going past his new ironstone mine in Hutton Lowcross, as “chimerical”; Joseph and his son, Joseph Whitwell Pease, drove it through and it opened on November 11, 1853. By 1856, it took 217,253 tons of ironstone out of the Peases’ mine; by 1865 Pease Jr was employing Alfred Waterhouse to build the fantastic Hutton Hall nearby at a cost of £88,000 (£8.3m today).

Other pioneers included Edgar Gilkes, an engineer on the S&DR, who joined forces with CA Leatham – Pease’s son-in-law – to form Tees Furnaces.

Two more S&DR men, William Hopkins and Thomas Snowden, formed Teesside Ironworks in the same year, and Isaac Lowthian Bell, the son of a Newcastle ironman, started mines near Normanby and built blast furnaces at Port Clarence.

In 1854, the Cochrane family of Staffordshire built the first furnace in Ormesby just as Bernhard Samuelson, from Liverpool, built the first furnace at South Bank.

Collectively, these men were the ironmasters, and their names still ring out on Teesside.

By 1860, they had more than 40 blast furnaces producing half-a-million tons of pig-iron a year. Middlesbrough’s population exploded from 154 in 1831 to 19,000 in 1861, and there was great pride in this being such a cauldron of activity, such a hive of industry, that the smoke from the furnaces blotted out the sun.

In October 1862, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, WE Gladstone, visited “Ironopolis”.

Even today, you can sense his amazement at what he saw.

With those ironmasters gathered before him at Middlesbrough Town Hall, he said: “This remarkable place, the youngest child of England’s enterprise, is an infant, gentlemen, but it is an infant Hercules.”

Hercules in classical mythology was noted for his superhuman labours, his extraordinary strength and his voracious appetite.

The infant grew rapidly.

The Peases extended their railway along the coast – Marske and Saltburn (1861), Skinningrove (1865), Loftus (1867) – and opened new mines to feed the voracious appetite.

To devour the ironstone, the blast furnaces grew in number – there were 90 of them by 1870 – and in size. Bolckow and Vaughan’s first furnaces were a mere 40ft high and 15ft in diameter. The new giants were the biggest in the country, 90ft high and 30ft in diameter.

BETWEEN them, they produced two million tons of iron a year – a third of the British output. In the hills, the mines were so widespread and interconnecting that during the harsh winter of 1870, food was taken in at Eston, walked through the empty seams and lifted up the shaft in Upsall to the surfacedwellers who were cut off by snow.

But the infant Middlesbrough suffered terrible growing pains. Iron was all boom and bust: boom in time of war, bust in the regular recessions.

The big bust came in 1874 after the Franco-Prussian War boom. Prices dropped ten per cent a month. Wages went likewise. Strikes broke out.

It coincided with stronger steel replacing brittle iron. A huge cloud hung over Cleveland as the local ironstone was thought to be too full of impurities to make the transition into steel.

But the new methods of the early 1880s fired another boom on Teesside. In 1883, new-look open hearth furnaces produced more than 300,000 tons of steel and consumed 6.75 million tons of rock dug out of the hills by 10,000 miners.

A new name emerged.

Arthur Dorman and Albert de Lande Long took over the defunct West Marsh Ironworks in 1875, rapidly applied the new technology and gobbled up many of the old ironmasters to create Dorman Long.

The adolescent Hercules was also consuming itself. By the early 1890s, the smaller mines were worked out and two million tons of iron ore was being imported a year from Spain to keep the furnaces fed.

The First World War created another boom. Dorman Long specialised in steel shell casings and invested £4.5m in a new plant in Redcar.

But then came another bust in peacetime as demand dropped and the mines were exhausted. To try to make financial sense of it all, in 1929 Dorman Long took over Bolckow and Vaughan to make one super-company, the biggest iron and steel manufacturer in Britain employing 33,000 men.

And probably the proudest.

The name “Dorman Long” is pressed into bridges around the world – Thailand, Egypt, Sudan, Denmark – and most famously, in 1932, into the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Even the Tyne Bridge, that Geordie icon, was made on Teesside.

Increasingly, the furnaces came to rely on foreign ore.

Eston mine closed in 1949 after 99 years during which 63 million tons of ironstone had been removed and 375 miners killed. The Great Cleveland Orefield finally finished on January 17, 1964, with the closure of North Skelton Pit.

But Dorman Long was still booming. In 1967, it became part of the British Steel Corporation as Harold Wilson’s government nationalised the nation’s 14 steel producers.

Teesside survived the rationalisation of the early Seventies when the 14 became five, and in 1979 the largest blast furnace in Europe was built at Redcar.

Margaret Thatcher privatised British Steel in 1988, which in 1999 merged with a Dutch company to form Corus. In 2006, Tata of India took over, and in 2010… We can but wait with anxious hearts as to how the next chapter unfolds.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here