THE return of Rocket to Newcastle for the first time in 156 years is seen as one of the highlights in the Great Exhibition of the North, which begins this weekend, but the real star of the show must be Killingworth Billy, whose place in history has suddenly been re-written.

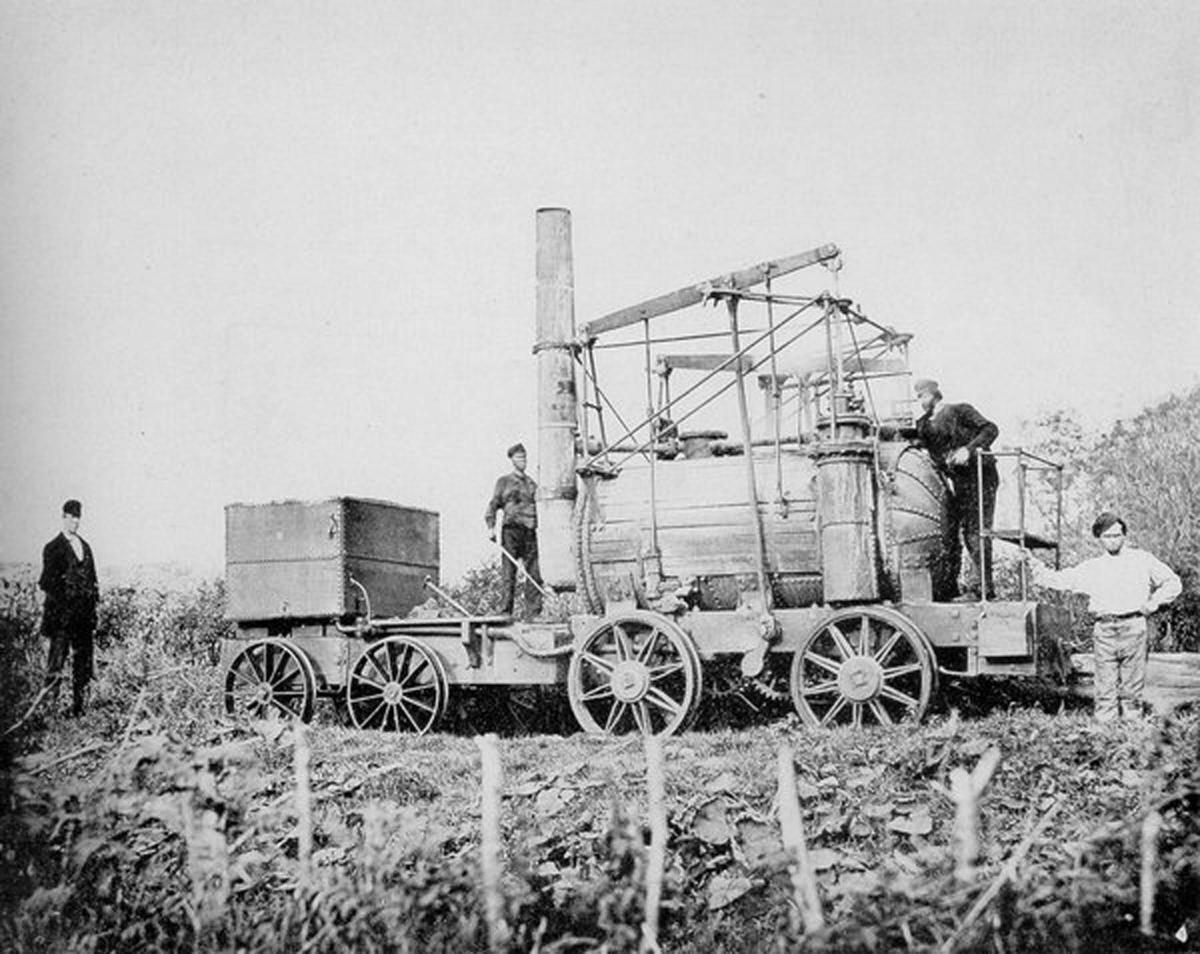

Killingworth Billy, which now lives in the Stephenson Railway Museum in North Shields, was previously believed to date from 1826, therefore making it an interesting relic from the earliest days of steam but not an important pioneering survivor – Darlington’s Locomotion No 1 of 1825, for instance, was ahead of it in the old engine stakes.

But new research suggests that Billy was built in 1816 and so is the third oldest surviving steam engine in the world, and the oldest standard gauge engine anywhere.

Billy is clearly extremely important.

The world’s oldest surviving steam loco is Puffing Billy, which is in the Science Museum in London. This Billy was built in 1813 by William Hedley with Timothy Hackworth doing the blacksmith work at Wylam, on the north bank of the Tyne.

Puffing Billy rushed along at a top speed of 5mph moving coal and wagons about a mile down to the Lemington staithes from where the keelmen rowed the coal in their keel boats out to the waiting collier ships which sailed it down to London.

Billy’s name probably came about because he was puffing like billy-o along the line.

Billy was enough of a success for Hedley to build the world’s second oldest surviving steam engine, Wylam Dilly, a few months later. A ‘dilly’ was a north North-East word for a ‘wagon’.

Billy and Dilly operated on a 5ft gauge – the distance between the wheels.

Not that Dilly, which is now in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, was always on land. In 1822, the keelmen went on strike, causing the coal to back-up at the Staithes, so Hedley attached paddles to Dilly’s wheels, sat it on a barge with its wheels dangling into the Tyne and set it going. Off it paddled to the colliers, hauling the keels.

George Stephenson was born in Wylam in 1781 and joined his father in the local colliery, taking a keen interest in the technological advances of the day. In 1812, he was appointed enginewright at nearby Killingworth Colliery, which gave him the opportunity to build his own engines.

His first was in 1814 and called Blucher, after the Prussian General Leberecht von Blucher, who was instrumental in the defeat of Napoleon in 1815. Blucher could haul eight wagons laden with 30 tons of coal at 4mph (that’s the engine, not the general) on rails 4ft 8ins (1,422mm) apart. This, with half-an-inch added to help with cornering, became “standard gauge”.

Stephenson updated his ideas in his subsequent engines until in 1821 joining forces with Edward Pease to create the Stockton & Darlington Railway and Locomotion No 1 in 1825. After that, it was believed that Killingworth Billy was one of several late 1820s engines that were built by Stephenson’s works.

But leading early railway expert Dr Michael Bailey has examined this Billy and has now concluded that the arrangement of its components such as cylinders, valves and wheel axles, plus its gauge, uniquely identified it as being built in 1816.

Geoff Woodward, a museum manager with Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums which looks after the Stephenson museum in North Shields, said: “Billy’s value in historical terms has been increased, not just because it’s the world’s third oldest, but because it feels like we have George Stephenson’s signature on it. Everyone has heard of Rocket – now everyone is going to hear about Billy too.”

So Billy has rocketed up the league of important old engines. The museum is to be re-engineered to give it greater prominence, and it features in the History of the North in 100 Objects, which is part of the Great Exhibition. Inspired by the exhibition, Dr Bailey will give a talk about his findings on July 21 at 11.30am (£6.50 for tickets) at the museum.

Billy rather puts Rocket in the shade, even though Rocket is the star of the Great Exhibition and it has returned home for the first time in 156 years.

Rocket was designed, like Locomotion No 1, by George Stephenson and built by Robert Stephenson & Co in Forth Street, Newcastle (Robert was George’s son). Rocket was complete in time for the Rainhill Trials of October 1829. Five locomotives competed for a £500 first prize and the honour of working on the Liverpool & Manchester Railway when it opened the following year.

Rocket used all the successful elements from Stephenson’s previous engines, and had a multi-tubular boiler which gave it the steampower to enable it to average 13mph over the 70 mile course. It even managed a top speed of 30mph.

Rocket won the trials ahead of Timothy Hackworth’s entry Sans Pareil, which can be seen in the Locomotion museum in Shildon, which is Hackworth’s adopted home town.

Of course, how much of these early engines really is early is debatable. No components exist on Killingworth Billy from 1816 even though that is when the engine was built. Parts wore out and were replaced and technological advances meant that some old bits were jettisoned in favour of new improvements.

Plus there were explosions.

For instance, Locomotion No 1 blew up in July 1828 at Heighington station, killing its driver and blasting bits into the neighbouring fields. It was rebuilt, and now has pride of place in Darlington’s Head of Steam museum, where it is billed as being the engine which opened the S&DR in 1825.

It is like having your grandfather’s axe in the shed – it is the axe your grandfather used, although it has had two new shafts and one new head since the days when he slammed it into a tree root.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here