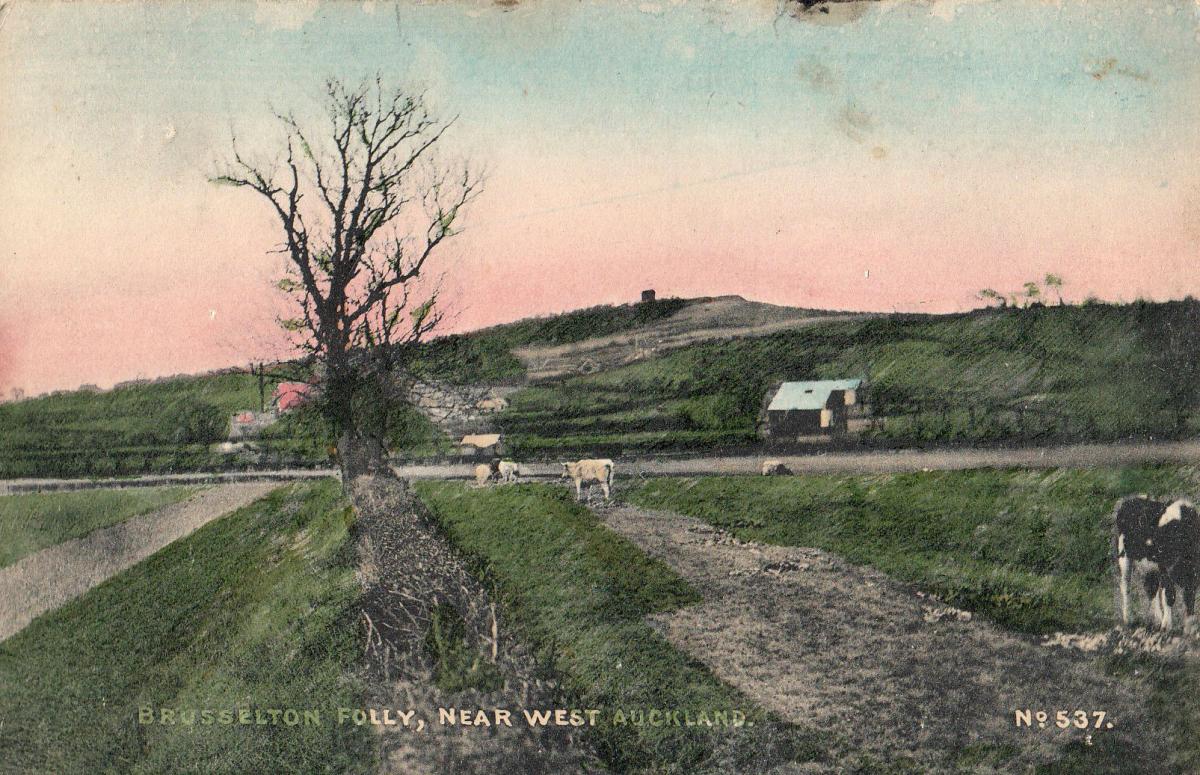

AT 250 metres above sea level – that’s more than 800ft – Brusselton is one of the highest peaks in south Durham. On a clear day, it is said that if you look to the east, you can see over Newton Aycliffe and over Middlesbrough to the cliffs at Saltburn more than 30 miles away.

And on the clearest of days, it is said that if you look to the west, you can see over Teesdale, over the Pennines, over Westmoreland, over the Lake District to the sea at Whitehaven more than 80 miles away.

You would need bionic eyes, or a truly terrific telescope, to be able to do that.

But it may be possible, on a clear day, to stand at the top of Brusselton and look north over Bishop Auckland, Durham and Chester-le-Street to see if any murderous Scots are rampaging in your general direction.

That may be why the Romans marched their principal street – Dere Street – from York, Catterick and Piercebridge over Brusselton before they walked along Bishop Auckland’s Newgate Street to camp at Binchester, their last rest before the frontiersland around Hadrian’s Wall at Corbridge.

And that may be why Cuthbert Carr built a tower on top of Brusselton in the mid 17th Century.

Cuthbert, who inherited St Helen’s Hall in the valley beneath Brusselton, had already had his fingers burned by some invading Scots.

Born in 1619, he came from a family of Newcastle merchant adventurers, members of which had occupied high office in the city for several generations. In 1643, Cuthbert himself was appointed Sheriff.

These were dangerous days. The Scots had allied themselves with Oliver Cromwell’s Puritan Parliamentarians who controlled London. But the North-East was resolutely Royalist…

A Scottish army approached Newcastle on February 3, 1644, and asked for its surrender. Sheriff Cuthbert, along with mayor Sir John Marley, was one of the city leaders who refused. In fact, it seems to have been Cuthbert who pulled down the homes of 100 or so poor people in the Sandgate area of the city to ensure the Scots couldn’t approach the walls unseen.

The Scots besieged Newcastle and rampaged as far south as York, taking control of the region –Wednesday’s paper told how Preston Park Museum in Stockton is to tell of the Battle of Yarm of February 1, 1843, a story told in Memories 341.

But Newcastle didn’t fall, so the Scots redoubled their efforts. On October 19, 1644, when the city leaders refused once to more to surrender, the Scots exploded three large mines beneath the city walls and then charged with battering rams. Cuthbert commanded the defence of the Newgate area, but he was quickly over-run and surrendered.

Although the Scots butchered many of the 1,500 Royalist troops they found in the city, they were remarkably kind to the leaders, and Cuthbert was allowed out with his life. He came south to St Helen Hall, at St Helen Auckland, which his family had built around 1620 – into living memory, outbuildings at the hall were known as “the barracks” which suggests he may have stationed some Royalist soldiers there.

One of the other great Royalist families of the district was the Byerleys of Middridge Grange – their men had fought so bravely for the king that they were known as “Byerley’s Bulldogs” – and soon after the siege, Cuthbert married Anne Byerley.

It is believed that to make sure the Scots never crept up on him again, Cuthbert built a look-out tower on the top of Brusselton. It is said that he connected it with his hall through a secret tunnel, and that a second tunnel went out from the tower to Middridge Grange two-and-a-half miles away. Thus the two great Royalist families always had a secret subterranean connection to their vantage point.

(Our area seems to be riddled with secret tunnels. It would have been an amazing engineering feat – and an amazingly expensive one – if Cuthbert had managed to tunnel underneath the River Gaunless and up the hill to Brusselton. However, in the 1930s a 200ft stretch of tunnel was discovered at Middridge Grange heading towards Brusselton so it must be true – or that could just be a drain.)

Cuthbert died at St Helen’s in 1697 and was buried in the churchyard. His descendants continued to enlarge the hall. In the early 17th Century, a Palladian wing was added, probably by William Carr, who was twice mayor of Newcastle and was the city’s MP from 1722 to 1734.

St Helen Hall is now a Grade I listed building, with its interior described as having “decoration of extraordinary richness includes enriched skirting board, dado and panel mouldings, pedimented supports with bolection frieze…”.

Which all sounds very grand.

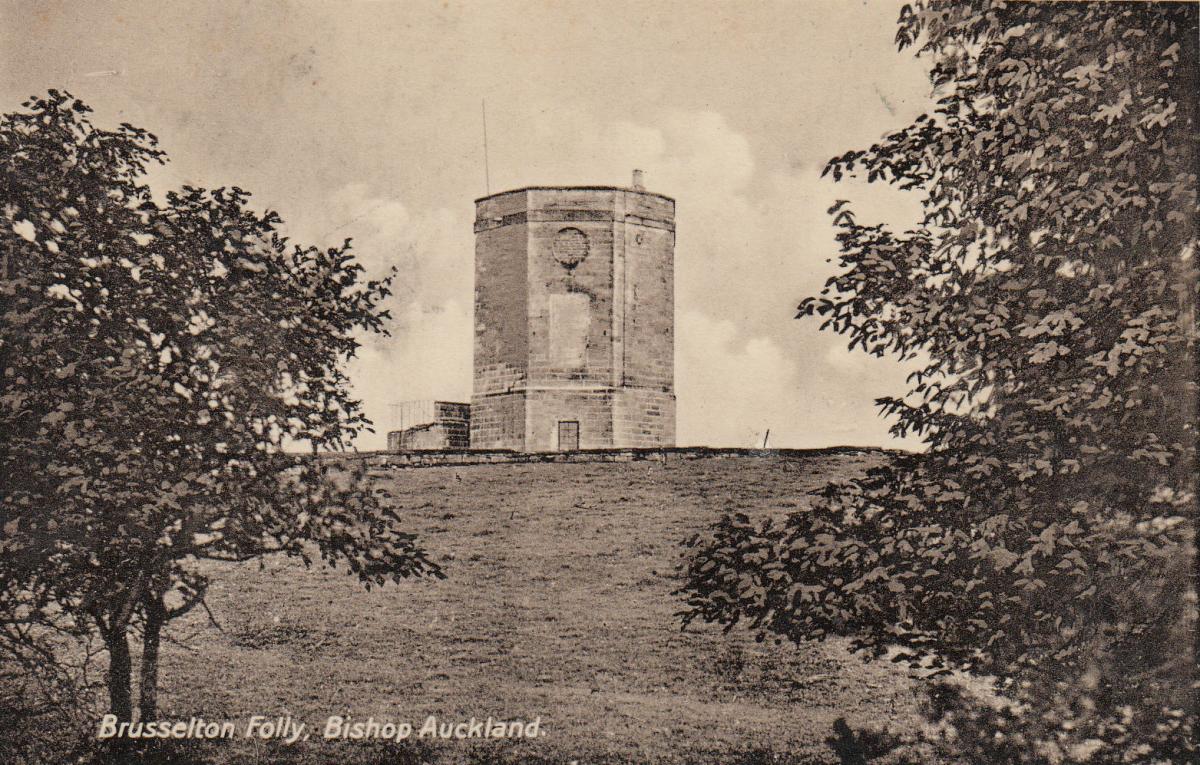

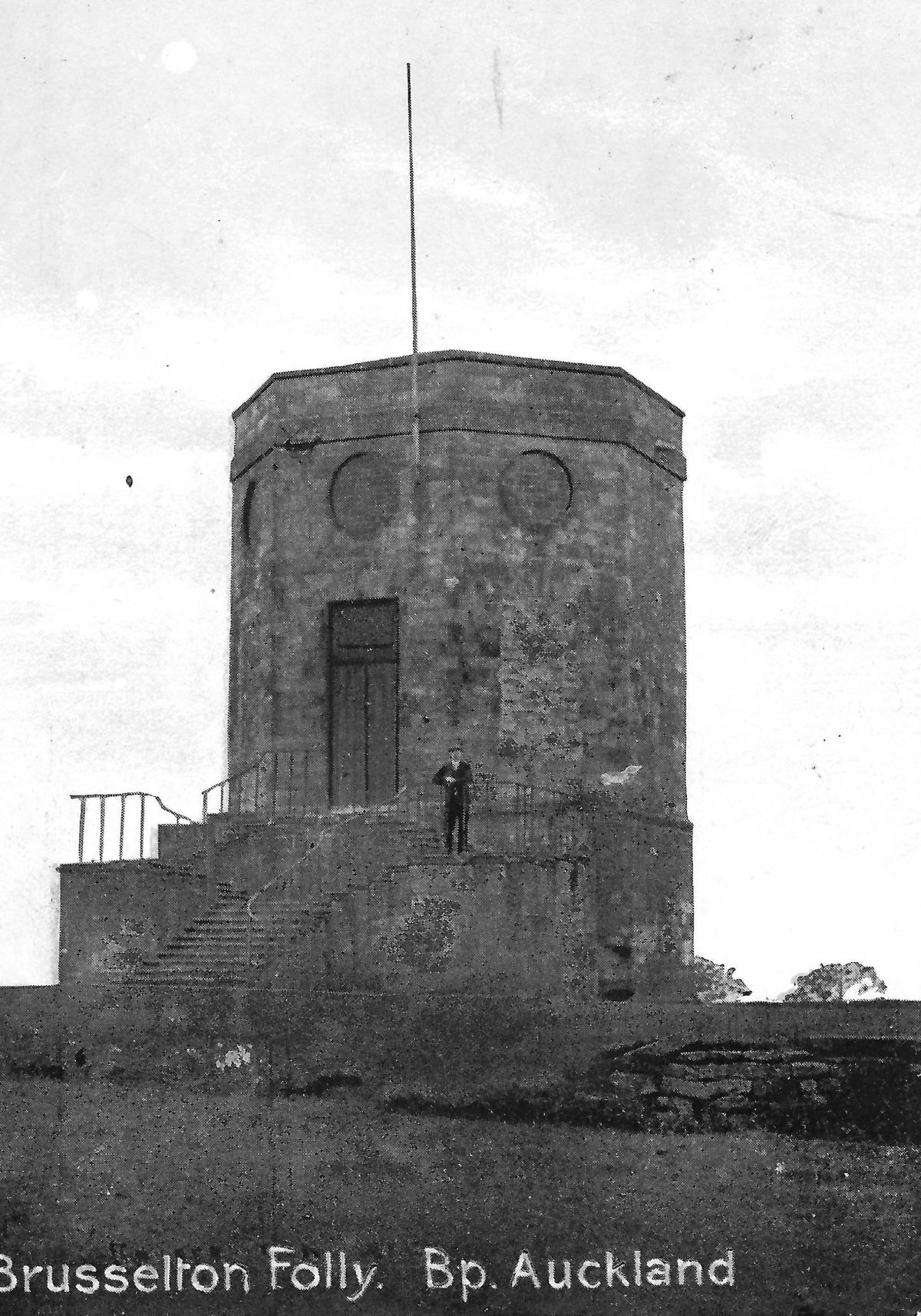

It seems likely that when William was enlarging his mansion, he was also turning the Brusselton viewing tower into a folly, or summerhouse. It was a perfect venue for a balmy evening’s picnic.

It was by now an octagonal tower, and the downstairs had a mosaic floor that was used for dances. Upstairs there was a sumptuous dining hall, its ceilings covered in ornate plasterwork and its views stretching from coast to coast (if you had a truly terrific telescope).

William loved to entertain here. A Victorian historian said: "He was a man of fine taste and unbounded hospitality, and who supported the character of a country gentleman with a splendour almost unparalleled."

Such was his extravagant splendour that by 1742 he was £8,364 18s 3 ½d in debt (about £1.7m in today’s values), and so when he died hall and folly had to be sold.

The new owners were the Musgrave family from Penrith, and in their time, the Stockton & Darlington Railway ran around the side of Brusselton hill – the brilliant work restoring the trackbed of the Brusselton Incline, beneath the tower, has been regularly featured in Memories in recent years.

The proximity of the railway inspired the search for coal, and the first pit was sunk in the shadow of the tower in 1834.

“There were 23 pits and borings on Brusselton hill at one time or another,” says Alan Ellwood, of the Shildon Recall Society, who got in touch, like many others, following a plea for information in Memories 348. “Opencasting over the last 60 years has erased most of the remains, although some of the airshafts are still to be found if you know where to look.”

The coming of industry probably reduced the lure of the folly for the picnickers from St Helen Hall, and over the course of the 19th Century the tower fell into disrepair.

During the First World War, it was used as a military observation post with “telephonic communication” to Shildon, Bishop Auckland and West Auckland.

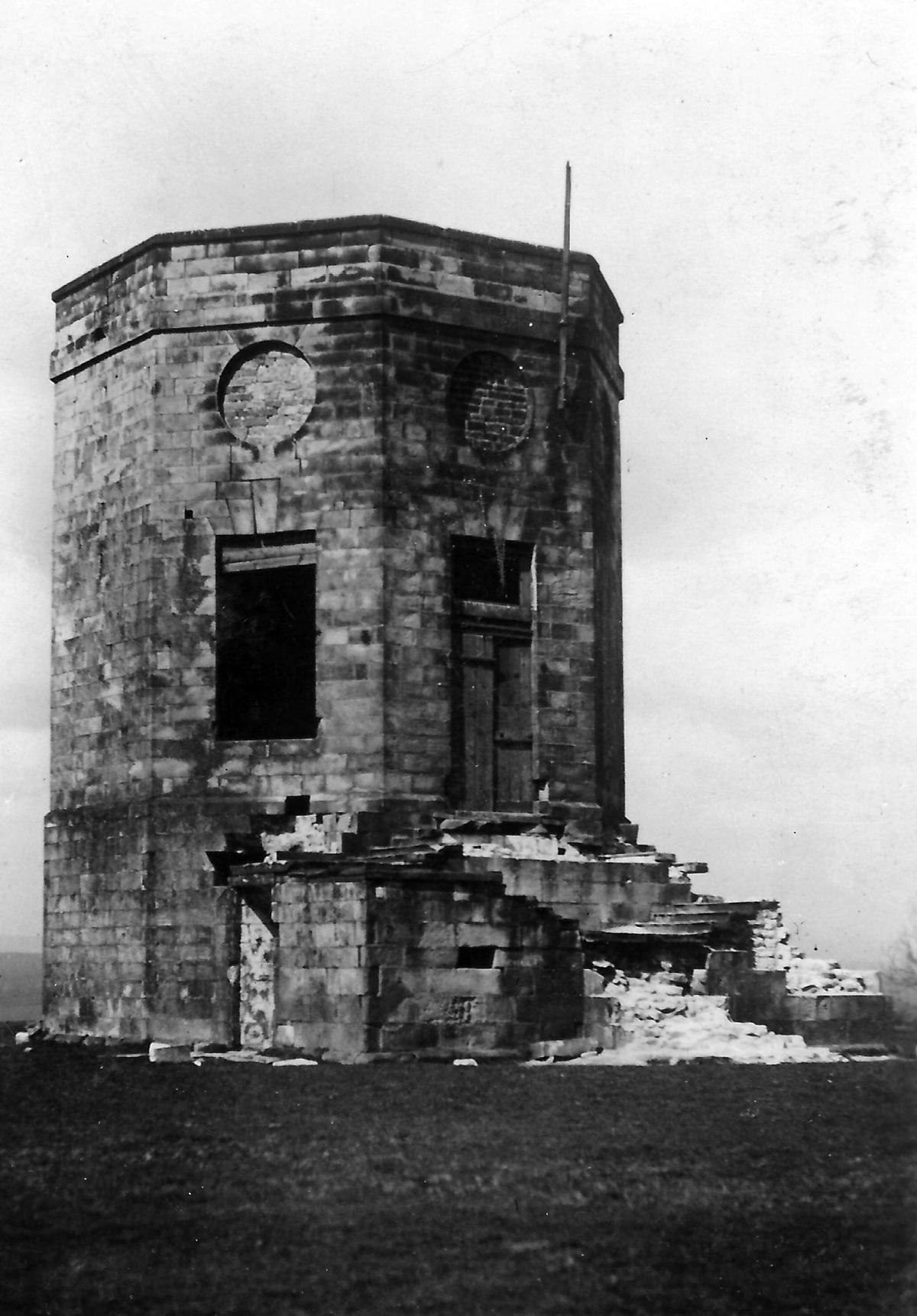

But its state continued to deteriorate. In 1930, concerned letters appeared in The Northern Echo and associated newspapers calling for it to be repaired. “The tower which has graced Brusselton for centuries is now a ruin and a reproach,” wrote JH Walker, of Coundon. “Children can no longer gather within its gaping walls. The circular room, with its leaded roof and beautiful ceiling, has now only the sky for a covering. The wind moans where laughter once rang and the raindrops dropping down its mutilated side seem like tears shed in loving memory.

“It can be repaired. But the stain of its mutilation can only be removed by a complete restoration. Will some of our local governing bodies move in the matter?”

The governing bodies remained stock still, but the folly was firmly established with nearby residents as a local landmark. It was a nice picnic destination for a stroll on a sunny day; it was a good hill for rolling hard-boiled Easter eggs down; it was a starting point for school nature and history trips, and it features as such in the 1945 public information film, Near Home.

It is said that during the Second World War, it interfered with RAF radar, but it survived into the 1960s.

“It was demolished around 1961 by the Parks family of builders – Syd and Maurice – on orders from the Ministry of Defence, which believed it was a strategic landmark that could have led to the targeting of the area during the Cold War,” says Alan.

In 1968, Brusselton Colliery, which employed more than 320 men, was closed and for more than a decade the derelict hilltop became a dumping ground. It was cleared up in the early 1980s, and although the post-industrial hard standing can still attract fly-tipping, Brusselton woods are a pleasant place for a stroll with good views and, on a clear day, you can still if the Scots are coming.

WE’VE agonised over our use of apostrophes and have concluded that the Carr family lived in St Helen Hall in St Helen Auckland.

So why isn’t it St Helen’s Auckland?

Our guess is that the name has nothing to do with St Helen, who was a 4th Century saint important to the church in Wales.

The ancient word “ellens” referred to a place with running water. Elin may even have been a pagan water god.

Darlington’s famous Skerne railway bridge was known when it was built in 1825 as Helen’s Bridge because it went over “the ellens”, or fields through which the river ran.

St Helen Auckland is low-lying beside the Gaunless – a perfect place to be called “ellens”.

Do you have any memories or information about Brusselton tower, or St Helen Auckland? Please email chris.lloyd@nne.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel