THE locomotive on last week’s front page was not all that it seemed.

It was known as the “Hetton” locomotive, and as our picture showed, it was given pride of place as the oldest engine on parade in the 1925 railway cavalcade.

The cavalcade celebrated the 100th anniversary of the opening of the Stockton & Darlington Railway, and the Hetton was allowed to serenely steam at the front of parade at six miles-an-hour because, according to the cavalcade programme, it was built in 1822 – a remarkable piece of surviving vintage machinery. But…

Landowner Robert Lyon first tried to find coal at Hetton in 1810, but was bankrupted by the venture.

Arthur Mowbray took up the scheme in 1819 and he confounded conventional wisdom by penetrating through the layer of magnesian limestone rock and finding coal beneath – geologists of the day said that it was impossible, but Mowbray’s discovery launched the east Durham coalfield which provided thousands of men with employment for the next 150 years.

The new colliery was known as Hetton Lyon, as a nod to the man who had lost his fortune trying to start it.

But for Mowbray to make money, he needed to get his new-found coal seven-and-three-quarter miles to a wharf at Sunderland from where he could sail it to London for sale.

So he called in George Stephenson. Stephenson was well known for his locomotive experiments on the colliery lines on Tyneside, and for Hetton he came up with the first railway in the world designed to be operated by steam locomotives.

There were, though, two large hills on the route, and the coal wagons were pulled up them by stationary engines fixed on the summits.

The line at Hetton opened in 1822, operated by four or five locomotives that Stephenson had probably built himself, possibly with the assistance of his friend, Nicholas Wood. They were rudimentary engines, and they were quickly overtaken by improving technology or they fell to pieces or they blew up.

In the 1840s, the colliery was taken over by Nicholas Wood who brought his son, Lindsay, on board. In 1852, Lindsay asked for a replica of the earliest locos to be made for sentimental reasons. It seems he wanted to prove that the engines that his dad and Stephenson had made were not museum-pieces.

However, although the exterior of the replica is said to have looked like an 1822 engine, internally it was fitted out with 1852 technology. This enabled the lookalike, named Lyon, to be put to work in the colliery, where people conveniently forgot that it was not the real thing.

Lyon retired from proper work in 1912 after a 66-year career. Due to its reputation as the oldest working steam locomotive in the world, it became something of a celebrity – which is why in 1925, it was placed at the head of the parade between Stockton and Darlington as a centenary of railways was celebrated.

But now, belatedly, we’ve rumbled it. Thanks to Ken Ottey of Easington Lane for pointing this out.

Yet it does have a claim to fame. It is the world’s oldest replica steam engine – perhaps one day, someone might even make a replica of it.

Now the Hetton Lyon is in Beamish Museum.

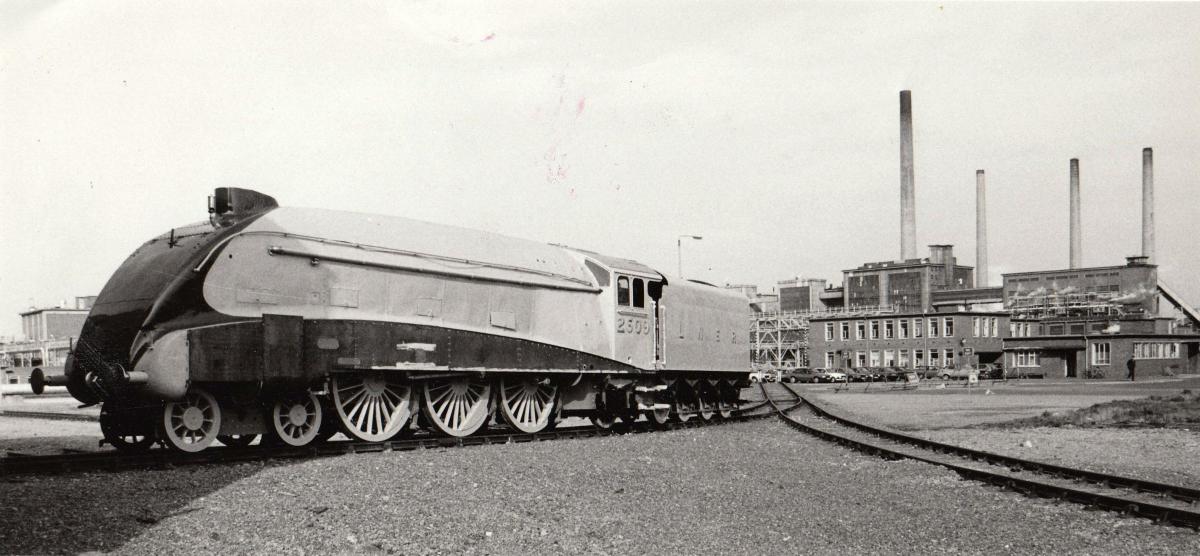

ONCE bittern twice shy, because one of the locomotives inside last week’s Memories was also not what it seemed.

We showed Bittern, an A4 Class locomotive built in Doncaster in 1937, dressed up to look its more famous sister engine, Silver Link, which broke the speed record in 1935. The engines was standing outside a power station, which we presumed to be Darlington’s as we were lead to believe it was part of the 1975 cavalcade.

How wrong we were.

“Bittern was indeed repainted as Silver Link but this was done in 1987-1988 in readiness for the celebration of the 50th anniversary of Mallard’s world steam speed record, of 126 mph, which was set in July 1938,” said Rodger Darbyshire of Darlington.

Peter Tarn, of Forcett, said: “As well as a full re-paint, Bittern’s transformation into Silver Link involved some engineering work to replace the side valences (removed during the Second World War to improve access for maintenance), and to replace the double chimney (fitted by British Rail in 1957) with a single chimney, as per the original construction. Your photograph shows the work on the valences at an incomplete stage, with some trimming and painting awaiting completion.”

Everyone agreed that this work was done at ICI Wilton, where there was an extremely large power station – “if Darlo had a power station that size you would be able to run the National Grid off it, which, of course, is just what ICI did”, said David Thompson.

But Bittern was not the only engine restored at Wilton by the North Eastern Locomotive Preservation Group (NELPG) in the 1980s.

Colin Hurworth said: “Bittern, together with Blue Peter, arrived on the Wilton site in 1986 for restoration, in No 5 Depot.

“Bittern was only cosmetically restored, renamed the Silver Link, and handed over to the National Railway Museum in York.

“Blue Peter was fully restored, and the process was often featured on the children’s Blue Peter TV programme, with Mark Curry and Diane Louise Jordan both visiting the site.”

Blue Peter – an A2 Class engine built at Doncaster in 1948 – has other connections to our area. For example, on March 1, 1994, when in Durham station, its boiler was overfilled causing an explosion, which left 300 passengers stranded and the driver injured. The engine was taken to Thornaby for more repairs.

Then, in April 2003, Blue Peter – billed as one of the most famous steam locomotives in the country – arrived at Darlington’s railway museum where it stayed until May 2007 when the museum’s upgrade necessitated its removal.

Blue Peter, which still occasionally appears on the TV programme, is now in Crewe being restored.

Bittern is currently awaiting restoration, although in 2013, pulling the Tyne Tees Streak, it reached 93mph, which was a record for a preserved steam locomotive, and in 2014 it was one of six A4s which featured at the Locomotion museum in Shildon in the “Great Goodbye”, which attracted more than 100,000 visitors.

THERE were several raised eyebrows about last week’s identification of engine designer Nigel Gresley as being the man photographed with the Duchess of York at the 1925 exhibition at Faverdale, in Darlington.

The Duke and Duchess of York – later King George VI and Queen Elizabeth – were the guests of honour at the 1925 centenary celebrations of the S&DR.

Richard Barber stepped in to clear up the confusion. “The gentleman with the future Queen is in fact Mr Smeddle, who was the manager of North Road works,” he said. “Mr Gresley was in fact standing to the right, with the Duke of York showing him a new Q6 loco fresh out of Darlington Works.”

Richard is giving a talk on the 1925 railway celebrations to the Stephenson Locomotive Society at the Newport Settlement Centre in Middlesbrough at 7.30pm on December 1.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here