Last week we told how exactly 150 years ago, Henry King Spark – “The Donald of Darlo” – tried to drain the town of the pernicious influence of the Peases through the creation of the town’s first democratic council. But the Peases regrouped and thwarted his bid to become Darlington’s first mayor, so he immediately launched a different bid to satisfy his lust for power – to become the town’s first MP

“WHAT faith can Darlington have in rulers like these?” wailed the Darlington & Stockton Times of December 14, 1867, after its proprietor, Henry King Spark, had been thwarted by the “Pease Party” in his ambitions to become the town’s first mayor.

“How can it trust its interest in the hands of men who have betrayed them? We believe that Darlington will answer these questions, sooner or later, in a tone that shall resound through the chamber of the town council.”

It sounds as though even in his moment of defeat, Mr Spark was already planning his next assault on the town’s Quaker ruling elite – the “Pease Party”. He had already successfully campaigned for the creation of the town’s first democratic council, which he hoped would water down the Pease Party’s power. With the formation of the borough, came the opportunity for Darlington to break from the Parliamentary constituency of South Durham and elect its own MP.

But by 74 votes to nil with one abstention, the local Liberal party chose Edmund Backhouse, head banker and key ally of the Pease family, to be its candidate in the 1868 General Election.

Infuriated once more by the Peases’ power-grab, Mr Spark decided to stand as an Independent Liberal, appealing direct to the working man as, Trumplike, he promised to take down the ruling elite.

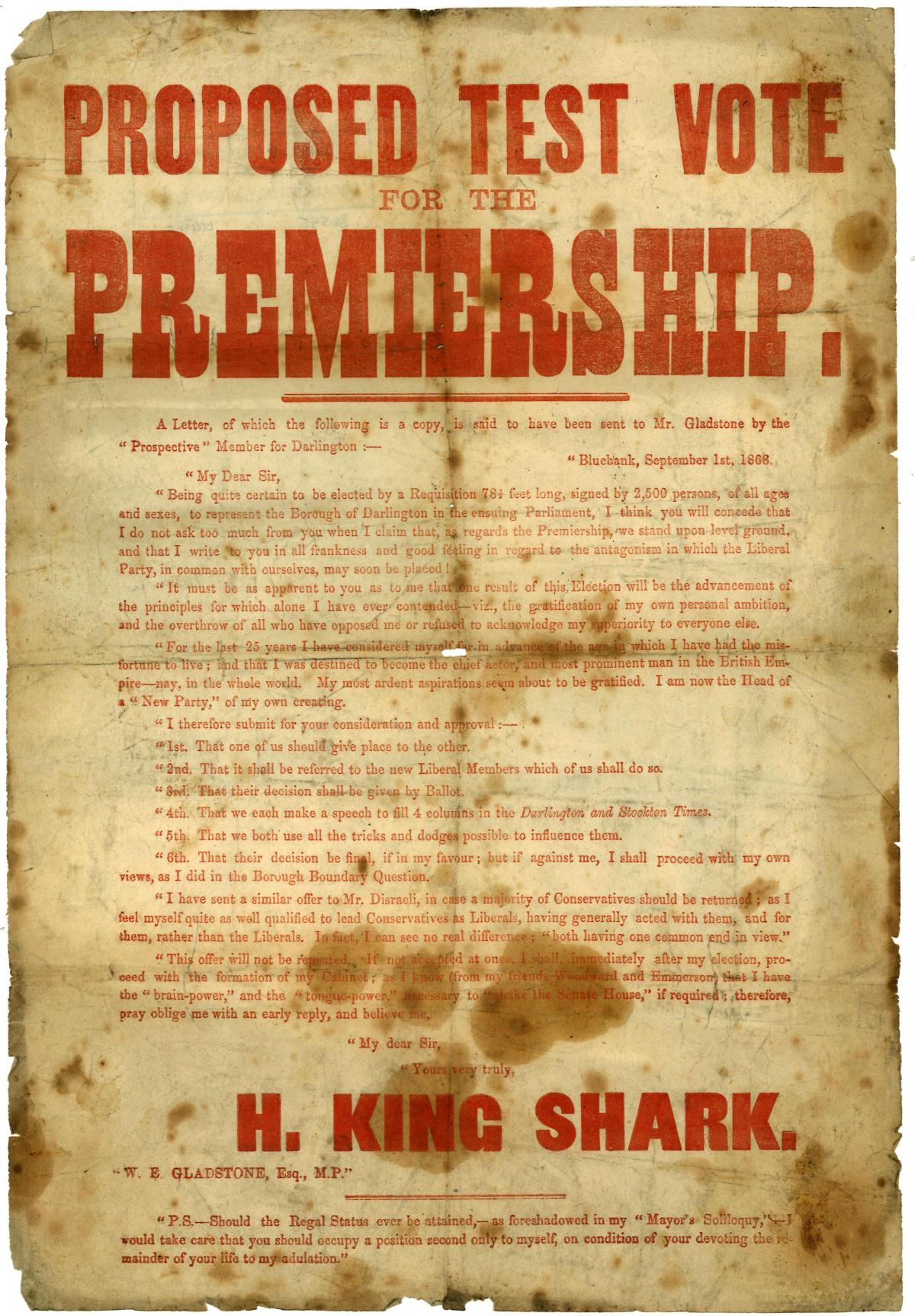

But such was his megalomania, his opponents printed posters which mockingly claimed he had told the Liberal Party leader, WE Gladstone, to stand aside and let him become Prime Minister and world leader.

Polling day was Monday, November 16, 1868, when up to 10,000 people (like Mr Trump’s exaggerated claims for the attendance at his rallies, it is difficult to believe Mr Spark’s counting of heads) gathered in the Market Place to hear the candidates speak from the old Town Hall balcony.

Then came the show of hands. According to Mr Spark’s D&S, it was three-to-one in Mr Spark’s favour, but Henry Pease – the town’s first mayor and returning officer – called it “indecisive” and so proceeded to a written poll, which was held the following Friday.

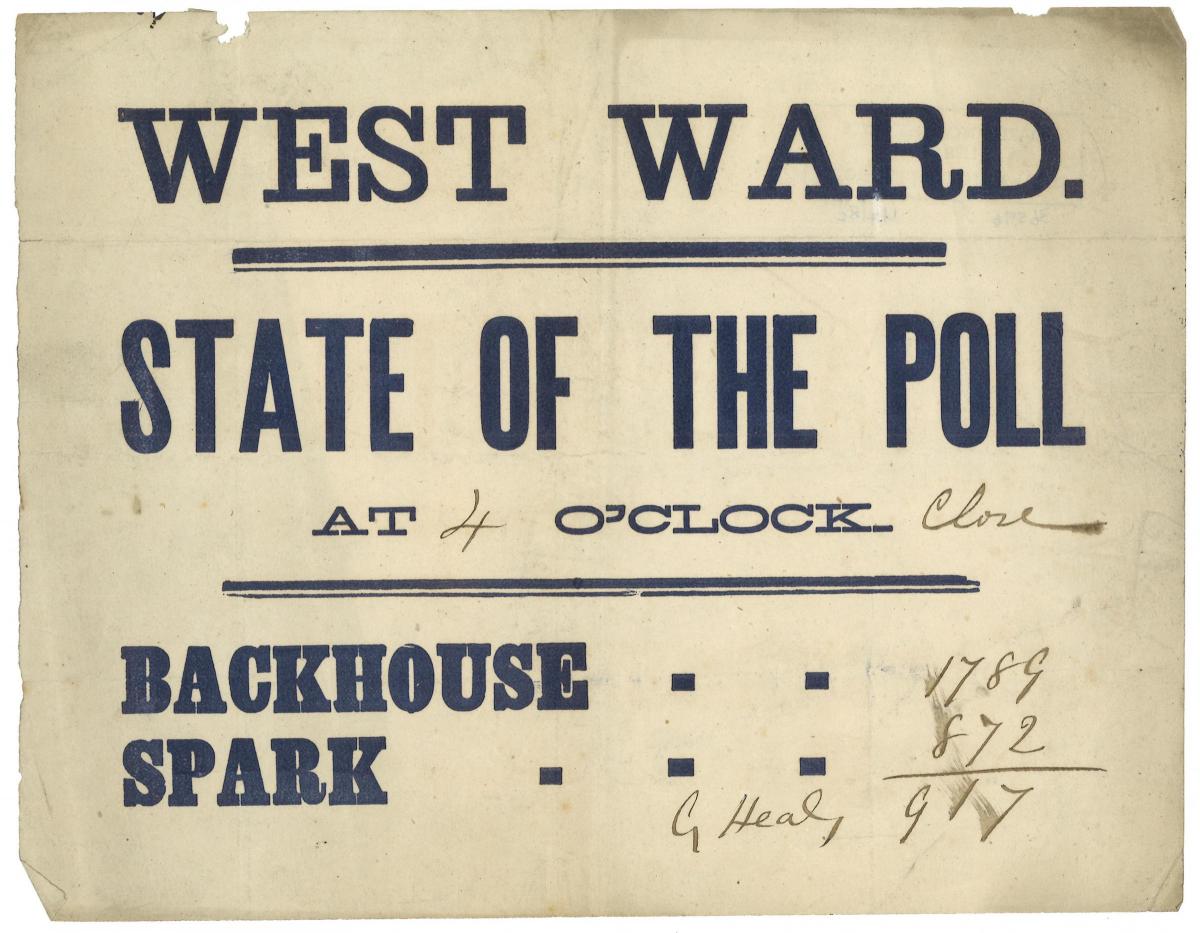

The result appears very decisive:

- Edmund Backhouse (Lib): 1,789

- Henry King Spark (Ind Lib): 872

But the next day’s D&S burst into outraged flames. It scorched: “On Monday morning, a show of hands more magnificent as regards numbers than any show of hands that has yet been displayed in Darlington was held up in favour of Mr Spark. Mr Spark represented freedom. Mr Spark represented independence. Unfortunately freedom and independence were a dead letter in Darlington yesterday. From street to street, from ward to ward, the screw was imposed in the most unblushing audacity. Early in the morning, ward after ward was visited, and in ward after ward, the screw was unmistakably present.”

Mr Spark’s accusation is that the Peases and their supporters used “every kind of corruption, intimidation and undue influence” to get the right result, and there are reports of members of the Pease family accompanying their railway employees into the polling booth and refusing to leave, even when asked, until the vote was cast for the right man.

Of course, we only have Mr Spark’s accounts in the D&S and its sister, the Darlington Mercury, to go on – but it seems no coincidence that just a few months later, the Pease Party had engaged one of the region’s leading newspapermen to start up a regional daily newspaper, to be called The Northern Echo, to blow Mr Spark’s local weeklies out of the water.

But Mr Spark did engage Mr Backhouse in Parliamentary battle for a second time, in 1874.

In the intervening six years, his spark had dimmed. His Merrybent Railway, which he drove to quarries near Scotch Corner, had gone bust (now the A1(M) follows its course) and he was on the verge of bankruptcy. He was embroiled in a nasty court case with his former partner Joseph Love – they had owned collieries together near Durham City – and he was accused of driving Mr Love to an early grave and then haranguing his widow.

Plus, a Conservative entered the fray: Thomas Gibson Bowles, the founder of Vanity Fayre magazine.

Having lost by 917 votes in 1868 and having seen his business reputation fade, and facing extra opposition, Mr Spark, as he addressed electors from a balcony above his campaign headquarters in a chemist’s shop in Tubwell Row, cannot have reasonably been confident.

But, in 1872 the Government had introduced the secret ballot. No longer could Peases hover over their employees in the booth, and so the result in 1876 was close:

- Thomas Gibson Bowles (Con) 302

- Henry King Spark (Ind Lib) 1,607

- Edmund Backhouse (Lib) 1,625

Once more the D&S burst into flames of indignation. On behalf of its owner, it railed: “Here was a great party with all the power that wealth, influence and position could give them. They had all the appliances known to electioneering craft… they bought up all the lawyers they could get hold of… they had gangs of canvassers scouring every street and alley in the borough… yet with all these means and appliances on one side, and the absence of them on the other, the nominee of the great Quaker party was only fluked in at the last moment by a majority of 18 votes.”

It is hard not to conclude that if the secret ballot had existed in 1868 when Mr Spark had been at the height of his popularity, he would have been elected as Darlington’s first MP.

The Echo rejoiced at his downfall in 1874. “It is a matter for public congratulation that the political career of Mr Spark has been so abruptly terminated,” said its editor, WT Stead. “He has done nothing for the town… he has consistently vilified its elected Member; he has misrepresented and abused its leading citizens.”

In 1876, he was declared bankrupt, driven from the town council, forced to sell the D&S and with his mansion – Greenbank (after which Greenbank Road is named). He ended up living near Penrith.

But his political career was not quite terminated because he stood for a third time, in 1880, against the Pease Party’s new candidate, Theodore Fry. This time, all the town’s newspapers trained their fire upon him – they called him an “undischarged debtor and vainglorious braggart” – and he was humiliated,

The result was a heavy defeat, by 2772 votes to 1,331: a crushing majority of 1,441. Immediately afterwards, the vanquished hero, the deflated Donald of Darlo, addressed his dwindling band of followers from the Bull’s Head in the Market Place and said: “Now, gentlemen, I have done. I leave you as you wish to be left.”

He was never again seen in Darlington. He moved to Startforth, Barnard Castle, and rehabilitated himself enough to be entrusted to read lessons in the church and to be elected to the Teesdale Board of Guardians.

He died in 1899 at his home, The Mount, near the Bowes Museum, and the only wreath at his sparsely-attended funeral at Startforth church was sent by a Wesleyan minister from Merseyside, who had started out as a penniless Durham pitlad. Mr Spark – who never married – had quietly taken pity on the lad’s widowed mother. He’d supported her while paying for the boy’s education.

So in death, a caring side to this curious character is revealed, but his last two mentions in the Teesdale Mercury are probably more revealing. In the days after his death, an advert was placed calling on all his creditors to come forward for a joint bid to extract their dues from his estate, and a couple of months after his death, it was announced that the lifesize portrait that he had presented to the town’s Mechanics Institute had now been hung in its building.

In 1869, a lifesize portrait of Mr Spark had been presented Darlington council. It was said that 3,000 of his supporters had contributed towards its cost to commemorate his glorious, pivotal role in the creation of the council.

Only years later, the secretary of the committee set up to collect the donations revealed that Mr Spark had secretly paid almost entirely for the painting of himself – it was just another part of his enormous, Trumpesque ego-trip which created Darlington Borough Council but led to his personal downfall.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel