HULL is the UK’s City of Culture, and it welcomed in 2017 with the largest New Year firework display in the country, watched by 25,000 people, and an art installation entitled “We Are Hull” projected onto its best known buildings.

One of those buildings was the Ferens Art Gallery, which is central to Hull’s year in the cultural spotlight.

The Ferens will reopen next Friday after a £5.1m refit, when its new acquisitions will go on show for the first time, including a rare Italian masterpiece by Valerio Castello which has been bought with the help of £350,000 from the Ferens Endowment Fund.

The word “Ferens” is clearly very important in Hull – as well as the gallery and the fund, Ferensway is the widest of five streets that include it in their name; there is a residential home, a park and a boating lake named Ferens, and even the university’s Latin motto – “lampada ferens” – maintains the theme.

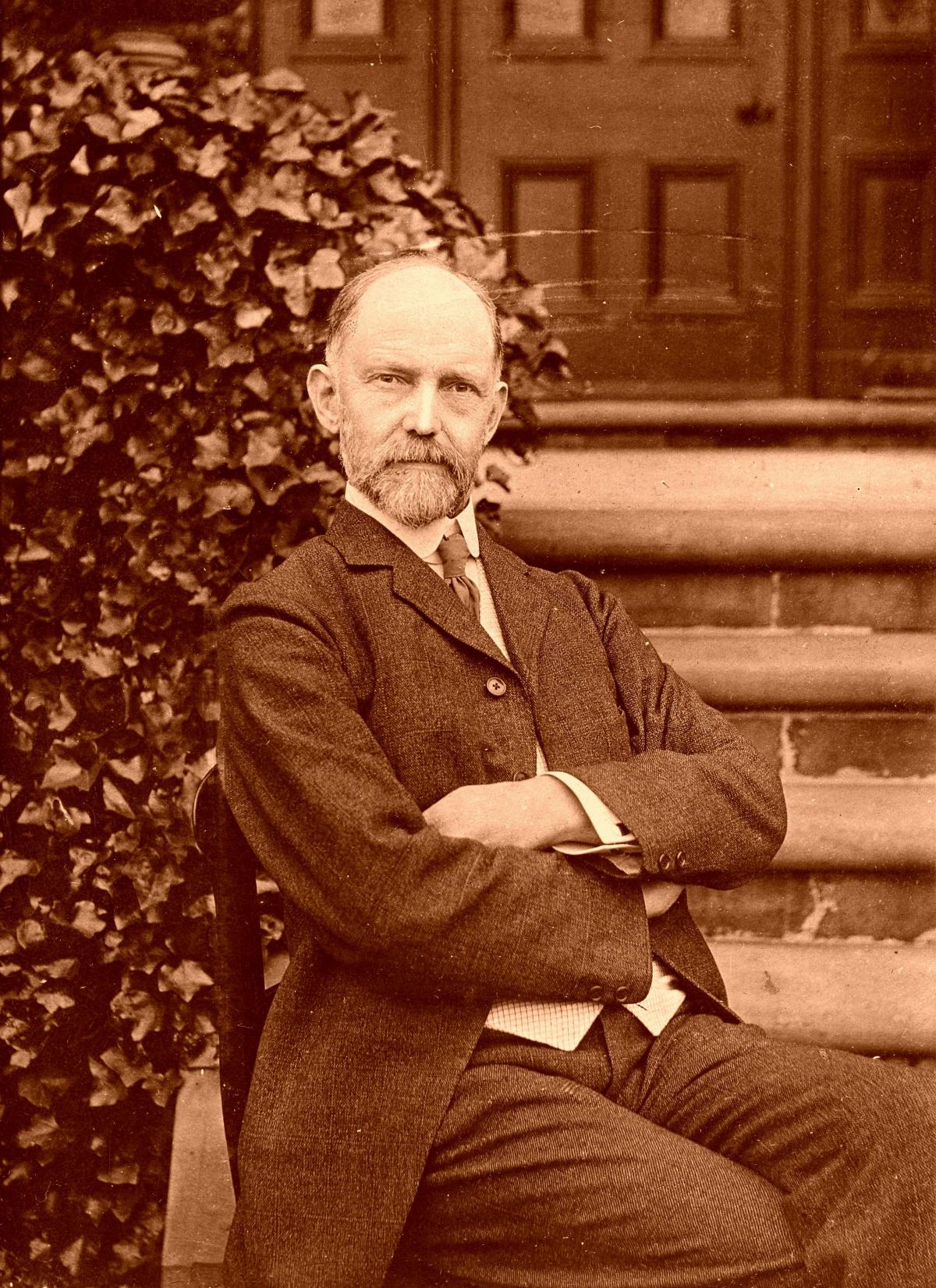

All are rooted from Hull’s self-made millionaire MP Thomas Robinson Ferens, whom the Hull Civic Society proclaims as “the most outstanding example of the public-spirited self-made man in Hull’s history”.

But Hull’s Ferens is a really a Durham lad. He hailed from Shildon but at the age of 16 went to Hull and never looked back.

Ferens was born on May 4, 1847, at East Thickley, which today overlooks the Locomotion museum at Shildon. He was the third of seven children of a miller, and was educated firstly in Shildon and then at the Belvedere Academy in Bishop Auckland. Aged 13, he got his first job, as a clerk in the Stockton & Darlington Railway’s mineral department in Shildon.

He stayed for six years until moving on to become a clerk at the engineering firm of Head, Wrightson in Stockton. He played cricket, but he studied hard by himself at night, and he taught at a Wesleyan Sunday school.

One of the skills he taught himself was shorthand – he practised by taking down the Sunday sermon – and in April 1868, he successfully applied to become the shorthand and confidential clerk to James Reckitt in Hull. Reckitt was one of three Quaker brothers who ran their father’s growing household firm, producing things like soluble starch, washing blue and black lead.

The shorthand clerk earned £70-a-year (but pledged to himself to give ten per cent away to charity) and arrived days before his 21st birthday at Hull station with only half-a-crown, which had been given to him by his mother, in his pocket.

But he immediately hit it off with his new boss, who was 14 years his senior. They shared a strict nonconformist world view – no alcohol but plenty of moral welfare and self education – and a love of County Durham: Reckitt’s wife of three years was Kathleen Saunders who came from Darlington, no doubt of good Quaker stock.

Ferens thrived. Within six years, he was promoted to works manager; within 12, he was general manager, within 20, he was managing director. With the Reckitt brothers, he transformed the company so that by 1914, it had merged with its principal competitor, J and J Colman of Norwich, and had become a multinational, its brands recognised around the world, employing more than 5,000 people. It is even bigger now: in 2006, Reckitt Benckiser bought Boots for £1.9bn and it includes brands such as Clear

Ferens was now pursuing his political ambitions. He became Liberal MP for East Hull in 1906, and held his seat until an acrimonious defeat in 1918.

Back in Hull, he concentrated on good works. He built the Reckitt model garden village with 600 semi-detached homes for the company’s workers. He donated £35,000 to start the art gallery; he gave £250,000 and 60 acres to found the university (its motto, “lampada ferens” means “carrying the lamp of learning”).

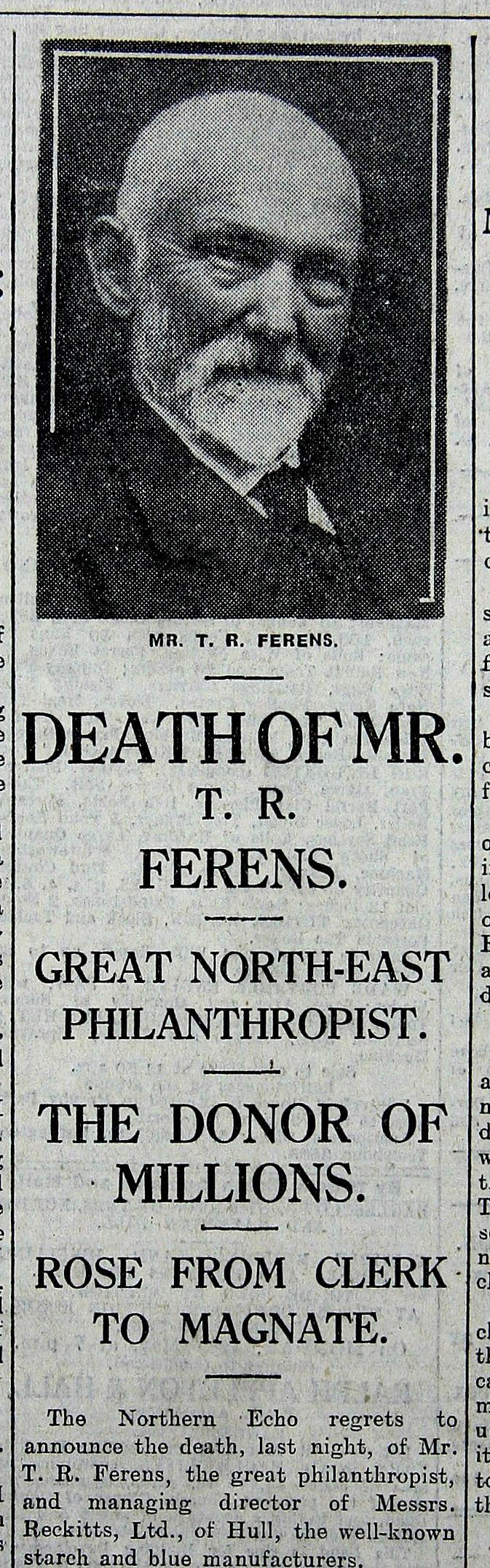

When he died in 1930, the Shildon lad who had arrived with a borrowed half-a-crown in his pocket had given away more than a million pounds and he left an estate worth nearly £300,000 (more than £17m in today’s values).

He had married, to Ettie, but had never had any children. Consequently, his estate went largely to charity. His home, Holderness House, became a rest home for poor gentlewoman – a function it still fulfils – and his gardens became a public park, with boating lake.

In its front page obituary, The Northern Echo said: “His life story is that of one who as a young man was possessed of few worldly prospects or advantages, but who, with the aid of that commonsense and grit so often associated with the industrial and social life of the Northcountryman, became one of the leading commercial magnates of the country, and one of the most princely philanthropists of his time.”

And the art gallery that bears his name is now featuring as one of the central attractions in the UK’s 2017 City of Culture.

THERE must be loads of local Ferens links. For a start, Thomas Robinson Ferens’ elder brother, Michael, followed their father’s footsteps and became a flour miller. In the 1870s, he took over the established mill at the bottom of Durham Chare in Bishop Auckland. Ferens’ Mill was large white local landmark until it was destroyed by fire in 1970.

On the left is Ferens' Mill in Bishop Auckland which was run by Michael Ferens. Picture: Tom Hutchinson

While we’re in Bishop Auckland, TR Ferens was educated at Belvedere Academy – that doesn’t have anything to do with the Belvedere Social Club in Kingsway, does it?

Then we are fishing for a link to the Ferens family of Durham City, the best known of which was Cecil Ferens, a solicitor who captained Durham County Cricket Club in 1929-31 and was mayor of the city in 1947-49. He gave £500 to buy an orchard in the Sands area by the Wear which became Ferens Park, the home of Durham City FC until 1994 – they’ve played at New Ferens Park until recently.

Cecil Ferens, who died in 1975, was a director of Ferens and Love, a mining company which owned Cornsay Colliery. One of the founders of Ferens and Love was Robinson Ferens, born 1819. And what was the middle name of Hull’s benefactor, TR Ferens – yes, it was Robinson. So there must be a link – who can help us?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here