THERE was widespread sorrow in the dales when George Stout died aged 31 on Christmas Day in 1918, just over two years after having his left arm blown off during the First World War.

His death was a devastating blow for his wife and three young children, and it led to one of the most unusual tributes paid to any war casualty – a football match played in his honour.

The aim was to raise money for his family. George – known to everyone by the nickname "Pompy" – was a hard-working miner and skilful footballer before the conflict.

He was only 5ft 3in tall, but was one of the stars of the Barnard Castle team. His short stature was no drawback in the Army either, as he was soon promoted to corporal in the Durham Light Infantry.

After losing his arm and suffering other wounds he received extensive hospital treatment before being invalided out in November 1916.

His discharge papers described him as a steady and temperate NCO.

Once back at his family home in part of the Blue Bell Inn in Thorngate, Barnard Castle (where Thomas Dobson was landlord) he got a job as a postman on a fairly arduous round in Langleydale.

He gained admiration as he walked briskly between the farms and houses every day with a smile and cheery word for everyone.

His death cast a gloom over the festive season and there was a big attendance for his funeral at Startforth Parish Church, where four soldiers acted as bearers.

Local footballers worked with impressive speed to organise a match for New Year's Day, a week after his death.

They had to get permission from the Durham FA and then find an opposing team to play a Dale 11.

The Army obliged by sending the York and Lancaster Regiment's side of fit and strong men.

The local line-up included several of Pompy's former team mates who hadn't played for a few years, so it was hardly surprising that the military squad won 4-0.

Despite the short notice and chilly weather, a sizeable crowd turned up, and a collection raised £15, which was given to Mrs Stout along with some further donations.

George's unusual nickname is thought to have come from a connection he had with Portsmouth, which is often referred to as Pompey. David Charlesworth, the dale's postal historian, uncovered details of the special match and is adding them to the mail history website. George is named on Barnard Castle's war memorial in the grounds of the Bowes Museum.

MANY boarding schools were run badly and with appalling cruelty in the past, as Charles Dickens found out when he came north to inquire about them in 1838. He showed his feelings about them in his novel Nicholas Nickleby.

But Gainford Academy was at the opposite end of the range, with first-class teaching and splendid facilities for sports and pastimes.

It was set up in 1818 by the Reverend William Bowman, a Congregational minister, and soon earned a reputation all over the region for its extremely high standards.

There were 80 boy boarders in the 1860s. Most were sent by well-off parents who wanted them to be properly educated. This was in contrast to other rich parents, who packed lads off to boarding schools just to get rid of them and had no interest in how they were treated.

Unlike many poor schools, which had no trained teachers, this one employed masters qualified in biblical knowledge, maths, English, music, drawing, shorthand writing, classics and drill.

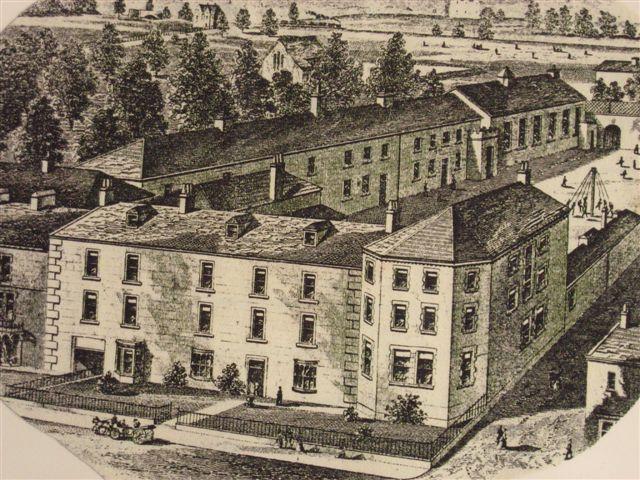

Its fees were 30 guineas a year for boys under ten and more for older pupils. Its buildings, as depicted in the illustration here, were top quality, and at the back there was plenty of room for games.

It had a well maintained cricket field on which the Eden Crest houses now stand, and tennis courts at Stoney Flatts.

There are now bungalows on the tennis land at Orchard Court.

"There was even a Turkish bath for the pupils and this was certainly one of the very best schools," says historian Mike Stow, who loaned the picture from his collection.

A lot has been written about Stanley Laurel, who was a pupil for a short time before finding fame in films with his partner Oliver Hardy. The academy had an annual bazaar over the Whit weekend. It was so famous that special trains were run to bring in visitors from Tyneside, Wearside and other places.

The picture is by George Tennick, an art master at the academy, who became well known for his portrayals of local scenes.

Sadly the academy started going into decline when the much larger Barnard Castle School opened in 1883.

In 1899 it was moved from the large premises into two houses in North Terrace by Bowman's son Frederick. It ran there on a reduced scale until it closed in 1914.

MEMORIES here about Wee Georgie Wood prompted Peter Jefferies of Durham to send in a reminder that the little star of stage and films was a close friend of another famous entertainer, Stan Laurel. They knew each other from their early days.

When Georgie was aged 12 he topped the bill in a pantomime, Sleeping Beauty, while Stan, who was four years older than him, had a minor role in it.

They lived not far from each other on Tyneside at one time, Georgie at Jarrow and Stan at North Shields. The pair regularly sent letters to each other throughout their long careers.

It is curious that both were in Teesdale for fairly brief spells in their younger days. Laurel was a pupil at Gainford Academy and Wood appeared in concerts in the stronghold ruins at Barnard Castle.

There is no doubt that in America, Stan told his film partner Oliver Hardy all about his diminutive pal's music hall triumphs back in Britain.

Peter Jefferies pointed out that both were featured by the Beatles. One track of their album Let It Be Me has a mention of Wee Georgie Wood, and the cover of their Sergeant Pepper album includes a picture of Stan Laurel.

AT this time of chilly weather, it is intriguing to recall that a man once died from sunstroke in the dales.

The temperature in Barnard Castle had soared to a remarkable 114 degrees on a June day in 1866 when 53-year-old John Morris collapsed in his garden.

The sergeant major in the 1st Durham Militia left a wife, Harriet, and eight children. Doctors put his death down to sunstroke, the first time this had happened in the area. There was a cold start to the year but a heatwave came in June.

Morris had seen a lot of action in the regular Army all over the world before joining the militia.

He started in the 60th Rifles, then served in the 31st Regiment. It was ironic that after facing danger so often he lost his life in his own garden due to sunshine.

He had been an important figure in the militia. He was buried with full military honours in Barnard Castle cemetery. Many soldiers attended to pay respects.

There was music from two Army bands, and three volleys were fired over his grave.

The Duke of Cleveland allowed his widow and children to live in a house backing onto the castle. Mrs Morris lived for another 28 years before passing away in 1894 at the age of 69. Thanks go to Susan Gardiner, of Startforth, for this information.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here