A hundred years after Smith’s Dock was built, the search is on for the men and women who made the proud ships that sailed down the River Tees.

ONE hundred years ago The Northern Echo was in full flow, words of history gushing from the pen of its reporter as if they were wavelets on the top of the Tees as it lapped its way towards the seven seas.

“Few towns in England can rival Middlesbrough in the rapidity of its growth,”

began the Echo’s report of October 23, 1907, headlined New Tees Dock.

“Fifty years ago, it could only boast a population of about 15,000 but it was beginning to take its place among the thriving industrial centres of North- East England. Now the flames from its myriad furnaces cast a ruddy glow over a town of 100,000 inhabitants, while clustered close around it, although outside its borders, are other busy industrial communities.”

It seems rude to interrupt the unnamed writer, so we’ll go with the flow of his colourful meanderings.

“In this wonderful development the river Tees has shared and played a foremost part. Thanks to the fostering care and lavish expenditure of the Tees Conservancy Commissioners, it has been transformed from a narrow, tortuous stream into a broad and majestic river, bearing on its bosom noble ships which carry to all parts of the world the metallic products of the busy workers on its banks.”

Are you enjoying the ride on a tide of words? We’ve nearly reached the point: “Yesterday saw the opening of a new chapter in the history of the Tees when the first coping stone was laid by Sir Hugh Bell of the new graving docks and shipyard that are being constructed for Messrs Smith’s Dock Co Ltd at an estimated cost of £250,000.”

Now some sharp bullet points.

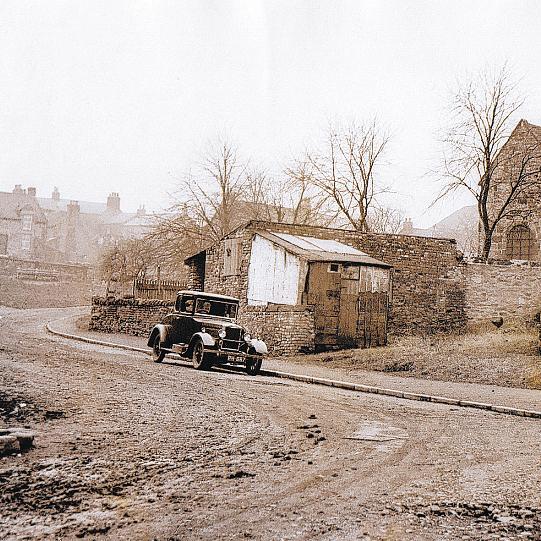

● Smith’s Dock began in 1810 when Thomas Smith bought a shipyard at St Peter’s, Newcastle.

● In 1851, on Tyneside, it opened a dock in North Shields.

● In 1854, on Teesside, Bernhard Samuelson, a Liverpool industrialist, opened the first iron blast furnace at South Bank. A community grew around it.

● In 1904, Smith’s found its trawler order book overflowing following its takeover of a couple of other Tyne yards. The Tees Conservancy Commissioners (TCC) were offering cheap mudflats on the Tees.

● In 1905, Smith’s Dock director James Edwards took 16 acres of mudflats at South Bank, enough for a shipyard and two dry docks.

● Excavations began in April 1907. All the earth dug out, plus 160,000 cubic feet of slag from nearby blast furnaces, was used to build up the mudflats.

● On October 22, 1907, the coping stone on the first dock was ceremonially laid by Sir Hugh Bell, and the Echo went into full flow...

“The vessels in the Middlesbrough Dock were decked with bunting for it was a gay scene as promptly at two o’clock, three vessels belonging to the TCC – the Sir Joseph Pease, William Fallows and Isaac Wilson – which had been lying in the dock cut, slipped their moorings, and, with bands playing and flags flying, steamed out into the river bearing the invited guests.

“The afternoon was delightfully fine and the sail down the river was thoroughly enjoyed by all on board. A little above the Fifth Buoy Light, the vessels turned and made for the landing at the dry dock. Here a platform had been erected, and upon this Sir Hugh Bell, supported by a distinguished company, took his place, while a large crowd gathered in front.”

The stone was “a huge block of granite” brought from the quarry in Egypt which was building the Assouan Dam.

Handing a trowel to Sir Hugh – an ironmaster who was mayor of Middlesbrough in 1874 and 1911 – James Edwards said: “I ask you to lay this stone firm and true, and I trust it may be a lasting memento.”

Appropriate, really, as the Teesside Industrial Memories Project (Timp) is collecting the memories of people who worked at Smith’s Dock.

“Sir Hugh, having spread the mortar and tapped the block of granite with a mallet, declared the stone to have been ‘well and truly laid’,” said the Echo, and 400 dignitaries repaired to Middlesbrough Town Hall for a splendid banquet.

In 1910, Smith’s Dock went into production. Of the 33 ships built that year, the first was a dredger named Priestman and another was a whalecatcher.

Whalecatchers would become surprisingly important to Smith’s.

In 1913, it expanded into two more dry docks and built three minesweepers for the Imperial Russian Navy, and in 1914, when war broke out, all of its part-built trawlers were requisitioned by the Royal Navy.

In 1915, to counter the new German U-boat threat, it built 15 submarine-chasers based on the whalecatcher design, and in 1916 the first women were drafted in to help build more minesweepers and patrol boats.

When peace arrived, the shipbuilding industry enjoyed waves of prosperity followed by long, quiet spells. In 1920, there were seven shipyards on the Tees.

By 1927, there were only three. Smith’s survived by converting merchant ships into whaling factories and, in 1925, building Lochside II which ferried beer casks between Montrose and Newcastle.

There was a boom at the end of the Twenties, with Smith’s launching a record 49 ships and employing 4,000 men at South Bank. But the early Thirties, depression was exacerbated for Smith’s by whaling restrictions, so in 1932 it launched only one ship – a French motor trawler called Fismes.

War, though, was good for business, and in 1940 Smith’s launched Gladiolus, the first of its famed Flower class of frigates, which kept it busy throughout the conflict.

On June 22, 1944, La Bastiaise, a French frigate, struck a mine off Hartlepool when undergoing sea trials.

It sank, taking several Smith’s employees to the bottom.

Pots-war, Smith’s built whalecatchers and cargo ships, coastal vessels for Scandinavia, tankers for Holland and colliers for France. Its last steamship was the Tynemouth, launched in 1955, and in the Sixties it supplemented its orders for bulk carriers with work on oil rigs.

Times, though, were tight.

In 1966, it was taken over by Swan Hunter and in 1977 the whole shipbuilding industry was nationalised. In the Eighties, Smith’s concentrated on large banana boats that plied their trade from the West Indies to London, and it built rollon/ roll-off ferries for Hong Kong, Brazil and Cuba. But when North Islands headed down the slipway on October 15, 1986, bound for Cuba, there was no more work.

“When Smith’s Dock closed on February 28, 1987, 1,348 people lost their jobs,”

says Julian Phillips, chairman of Timp.

“Half of them lived in South Bank, and it had a dramatic, devastating and lasting effect there.”

The memories project is particularly keen to speak to women who did industrial jobs at the yard, such as drivers who took sheets of steel from the stores to the slipways, and rivet-catchers.

“We also want to talk to young people, those who were in their 20s at the time of closure, to find out what happened to them afterwards,” says Mr Phillips, whose group is following up its successful book of oral history called Life at the ICI with this work on Smith’s Dock. Anyone interested in contributing should email timp@uncommercial.co.uk or call 01751-431547.

BACK to batteries. You will remember that we have distinctive raised plots of land near railway lines called Batteryside or Battery Top or The Battery in Durham City, Tudhoe, Latherbrush Bridge, near Bishop Auckland, and Escomb. Our best guess was that they got their name because they looked like the earthen gun emplacements – batteries – that British armies had been heaping up for centuries to better batter their enemies.

But Gill Wootten and Ron Lewis, both in Darlington, urge us to look more closely in our dictionary.

There we find “batter”, which is a technical term for slopes that “recede from the ground upwards”.

“In my engineering days, the slopes on motorway cuttings were all called ‘batters’,” says Ron.

“I remember as a child asking my father why the retaining walls of the Parkgate approach to Bank Top station were so curiously curved from base to top and being told it was a technique known as “battering” which increased their strength,” says Gill.

Which is why we have so many battery-related names on the edge of battered railway embankments.

STILL with the dictionary, a couple of weeks ago we were struggling with Thomas Metcalfe’s 1828 riddle. One line had us perplexed: “A word Roger uses at Plough to his Cattle”. The answer to the riddle was Nottingham, and so this line must be “g”, as in “gee-up”.

To us careless folks today, cattle are purely cows in a field, but Alan Wilkinson in Barnard Castle points out that in olden times almost any domesticated animal, including horses, fitted the term “cattle”.

Indeed, says Mr Wilkinson, any barely domesticated creature could come under cattle.

For example, this is a line from novelist Samuel Lover’s 1845 tale of Irish life titled Handy Andy: “Women are mostly troublesome cattle to deal with.”

MENTION of Escomb prompts an email from Tom Robson, who spent “the first 40 of my 85 years” in the village near Bishop Auckland.

He says a searchlight unit, not an anti-aircraft gun, was posted on the raised ground near the railway line. The stiles on the footpaths around were guarded by sentries.

“As a schoolboy, I had to leave home at 5.30am to walk to Bishop Auckland to catch the early morning train to Barnard Castle. On summer mornings I walked unchallenged through the fields many times past the sentry, who was fast asleep on his feet, leaning back against his truck,” he says.

MR ROBSON’S letter is in full on the Echo Memories blog, on the Echo website, as is the correspondence on Tudhoe and Molly Dolly which we can’t squeeze in today.

There’s just room to return to last week’s North Durham MP, coal-owner and cablelayer Sir George Elliot. His great-nephew, Norman Elliot Robson, lives in Darlington with his wife, Joyce, where they know snippets of the family story.

One snippet concerned 1874, when George received his knighthood. He was so pleased, the story goes, that he kissed Queen Victoria’s hand.

You will remember the furore in 2000 when the Australian premier dared to put his hand gently on the Queen’s back, so can you imagine the furore 136 years ago when this rough- Durham-pitman-made-good smacked his kisser onto a regal finger.

SIR George was able to make good because of his education. He started down Penshaw pit when he was nine but spent a quarter of his wages on George Watson’s mathematical nightclasses in Chester-le-Street.

Dorothy Hall, chairwoman of Chester-le-Street Heritage Group, says: “As a retired teacher, I have always treasured Sir George’s quote about George Watson: ‘He enabled me to hitch my wagon to the stars.’ “An aim for all teachers!”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here