Germans arrive in Darlington to break a tailors’ strike and trouble ensues, as Echo Memories reports.

THE year of 1866 was strewn with strikes and industrial strife.

Anyone who was anyone was out: puddlers, moulders, ironworkers, joiners, ship-joiners, masons, bricklayers, brickmakers, shoemakers, tailors… The American Civil War, which started in 1864, had created an economic boom in Britain, particularly in the iron industry, which had worked overtime to supply the war needs.

Peace reduced demand.

Ironworkers’ wages dropped.

They went out on strike, backed by the first unions.

Across the Tees Valley, 2,700 blast furnacemen and 12,000 ancillary ironworkers were idle.

In May 1866, the London Quaker bank of Overend, Gurney and Company collapsed – the first “Black Friday” and the last run on a bank until Northern Rock two years ago. It had very close connections with the Quakers who ran south Durham and its demise caused further industrial shutdowns.

The economic turmoil stoked fears within the working-class; fears of cheap foreign labour coming in and stealing their jobs; fears of new-fangled steam machines coming in and stealing their jobs.

The fears spilled over into strikes, one of the most bitter – and most surprising – was among the tailors of Darlington.

The journeymen tailors went out on strike in June 1866 “on account of the majority of the masters having refused to pay them for sewing coat edges”, explained the Darlington and Stockton Times.

The local dispute coincided with a sevenmonth national tailors strike. In Manchester in August, 700 tailors were locked out by their bosses and foreign workers were brought in to replace them.

In London, Karl Marx’s International Workingmen’s Association intervened for the first time in a strike. It placed adverts in newspapers in France, Belgium and Switzerland urging their tailors not to come to London to steal the strikers’ jobs. Instead, in a gesture of solidarity, the foreign tailors sent money to the strikers.

Darlington’s tailors united with fellow strikers from Bishop Auckland, Hartlepool and Manchester (Durham’s tailors were also out and may well have been involved), but this only drove the Master Tailors – their bosses – to Edinburgh, where 100 German tailors had been imported to break the Scottish strike. George Stephenson, the leader of the Darlington Master Tailors, recruited 15 German tailors and returned with them to Bank Top on the 6.43pm train.

He placed them in a lodging house – run by Mrs Nelson – which, the moment his back was turned, was stormed by angry strikers.

They drove the Germans across town until Mr Stephenson found them sanctuary in the Station Hotel, in Hopetown.

“A large crowd collected in front of the house, amongst whom were 20 or 30 tailors using threatening and obscene language,” said the D&S Times.

At least one of them, Edward Cawfield, burst into the pub and accosted Mr Stephenson as he tried to protect the Germans.

Mr Cawfield “seized Mr Stephenson by the beard and a struggle ensued, in the course of which the hat of complainant (Stephenson) was crushed, his coat torn and his head bruised”.

The stand-off continued late into the night. A couple of days later, Mr Cawfield appeared before magistrates and was fined ten shillings for assaulting Mr Stephenson.

The tailors held a meeting the following week at the Crown Inn, in Skinnergate, and sent a conciliatory letter to Joseph Webster, secretary of the Darlington Master Tailors’ Association, asking for arbitration.

Mr Webster sent a stunningly inflammatory reply, rejecting the offer. He concluded: “Not only have the masters succeeded in getting other workpeople, but they have got better workmen – such as know how to treat an employer with civility.”

Even angrier tailors wrote to the papers saying that the Germans had been poached from Edinburgh because the Scots had seen how poor they were.

“The workmanship of the German tailors will not stand the wear and tear of the English tailors,” said John Harrison, of Hurworth Lane, a tailor of 30 years’ standing, “and they will not stay their work the same as the English do, and this thing alone renders their work good for nothing.”

Despite all this fury, the Darlington tailors’ strike seems to have fizzled out. It was not mentioned again by the D&S Times in the last quarter of 1866. The dawn of 1867 saw the economy improve and the wave of strikes abated. Even, as Echo Memories told a fortnight ago, Darlington’s Covered Market and Backhouses Bank – the two big construction projects of the time, which were held up for months by the strikes – were completed.

And so we are unable to satisfactorily answer the query of Colin Bainbridge.

Deep in his family tree is Dietrich Nottger, a German tailor, who married at St Cuthbert’s Church on July 18, 1865 – the summer before the dispute. Was he somehow connected with the striking shenanigans?

Herr Nottger must have been a cut above the “good for nothing” German tailors.

Family legend has it that he made the gowns for the mayors of Darlington.

THE 1866 strikes created heroes, none more so than John Kane, who became the champion of the Tees Valley ironworkers. Echo Memories told his story in 2002 – it will be posted this morning on the Memories blog on The Northern Echo’s website.

Then there was James Hodgson, president of the Bishop Auckland branch of the Amalgamated Cordwainers’ Association.

The strike by the Bishop cordwainers – or shoemakers – was every bit as bitter as that of the Darlington tailors. The master shoemaker was a Mr Longstaff, who had workshops in Bishop, Crook and Spennymoor. When his men struck, he locked them out.

Non-union members were pressurised to join the strike; unemployed shoemakers from Tyneside who came south looking for work were shown the error of their ways and forcibly escorted to the station and into the railway carriage that took them home.

Mr Hodgson was found guilty of intimidation and sentenced to three months’ hard labour in the Durham House of Correction.

However, on appeal to the Queen’s Bench, in London, his conviction was overturned and his release was ordered.

His colleagues walked triumphantly to the jail “and after procuring Hodgson his freedom, a message was despatched to Auckland that they might be expected by the 6.20 train”, reported the D&S Times.

Accordingly, a very large number of working men of all trades, as well as the men out on strike and the Auckland Brass Band, assembled at the station for the purpose of giving him a hearty reception, which they did. The party on alighting formed into procession, and proceeded into the town headed by the band.

“When the procession reached Mr Longstaff’s shop – the source of the strike – the shouts and cheers were deafening.

“The procession then proceeded along Bondgate, and to Hodgson’s home, where, after giving him several hearty cheers, he was left.”

Riseburn remembered . . . but not by the registrar

RISEBURN is a lost industrial settlement of County Durham.

It was within hailing distance of Eden Pit, which has also withered away.

Both communities, near Middridge, were mentioned here several weeks ago under the headline “Come friendly bombs and fall on…Eden”.

They weren’t the most salubrious of the places.

Nevertheless, Eva Stainsby kindly emailed from Ferryhill: “Oh how you made my day with your mention of Riseburn. My late husband, Ean Munro Stainsby, always maintained he was born at “Riceburn”

in January 1932. His father died in 1934, so Ean knew very little and his mother did not talk about him, so we could never back up his claim. When he died, the registrar could not raise Riceburn on her computer, so for his birthplace she just used Brandon, where his birth was registered. But he always said “Riceburn” was near Middridge.”

In south Durham dialect, “rice” were the scrubby plants that grew in boggy places. True Darlingtonians, for example, pronounce the district to the north end of their town as “Rice Carr”. It is only the mapmakers and the signpainters who stuck an s in the middle.

Riseburn – it must have been a little stream in which scrub grew – consisted of 41 houses in three terraces set in a U-shape, with a Methodist chapel in the middle.

Among the Stainsby family’s possessions is an undertaker’s receipt dated 1920 – it is for a coffin for a stillborn child who would have been Ean’s oldest brother.

Ean’s non-Durham name reinforces the impression that Riseburn was a place where people arrived looking for work and a foothold in the Durham coalfield.

Don Ferguson has also been in touch. Deep in his family tree is George William Metcalfe, who was born in Arkengarthdale in 1868. He married Selina Downes, daughter of the publican in Middridge in 1890, and the 1891 census found them living in Riseburn.

“When we were looking for information about the place in 1996, I had not yet retired and one of my then customers lived and ran a business practically next door to where the village stood; literally, just over the hill. He’d lived there all his life, yet he was totally unaware of its existence,”

says Don.

Reinforcing Riseburn’s reputation as a place for transitory people, Mr Metcalfe, from Arkengarthdale, moved from there to New Zealand.

Riseburn’s terraces and chapel were probably demolished before the Second World War.

One house was spared, though, to accommodate a farmworker.

The last resident of Riseburn then was Kenneth Kilburn, now of Eldon Lane.

He remembers the Urban District Council of Shildon’s decision to demolish in 1963.

“There was just a well for water and oil lamps,” he says.

“It was an end house of one of the rows.

“We had part of it converted into a byre and piggery, but it was condemned as ‘unfit for human habitation’.”

He finishes with a little nugget about Riseburn’s terrible twin.

“My uncle was one of the last people out of Eden Pit,”

he says. “He was the caretaker of the community centre which had been the village bath where you paid 1d.

“Everybody had tin baths so you went to the village hall.”

Book of postcards plots town’s history

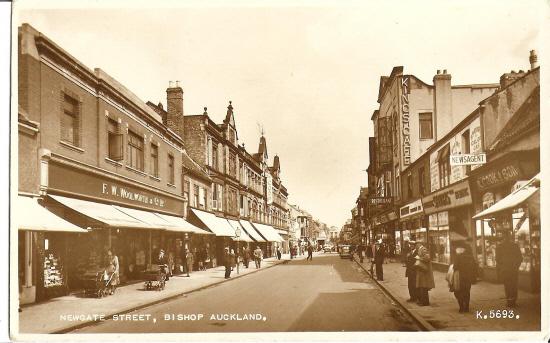

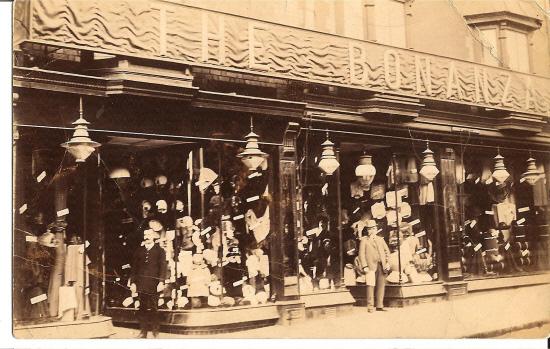

BISHOP Auckland historian Tom Hutchinson launches his latest book tomorrow, from 10am until noon, with a signing session at his exhibition in Bishop Auckland Town Hall. The book, which costs £5, is called Bishop Auckland: A Century of Postcards. It contains more than 100 postcards from Tom’s collection, most of them from the golden age of postcards – 1902 to 1914. The exhibition of enlarged postcards runs for three weeks. Tom will also be signing books at the Locomotion railway museum, at Shildon, during its history fair on Saturday, from 10am until 1pm.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here