Chris Lloyd tells the story of the Battle of the Standard, which is being remembered over the next week in Northallerton

IT is 880 years since a quiet triangle of North Yorkshire countryside was a tumultuous battlefield, the air filled with arrows and screams, the ground covered with the dead and the dying.

Today, where cows graze, crops grow and buffalo roam, thousands of men were hacked, speared, pierced and butchered to death – so many of them that after the birds and the beasts had picked their carcases clean, they were buried in huge holes which give their name to an old track which runs across the centre of the battlefield.

Scot Pits Lane it is called.

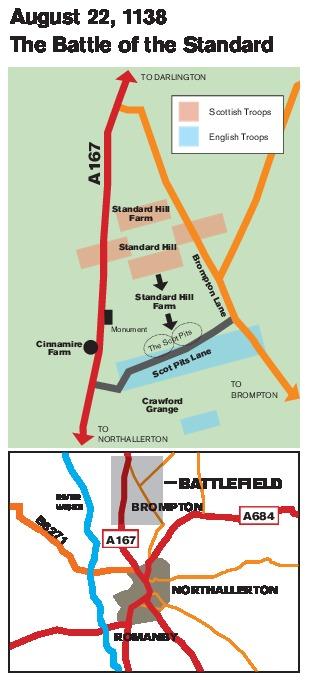

The quiet triangle of countryside is a couple of miles to the north of Northallerton. On its east side, it is bounded by the Great North Road – now the A167 – running up to Darlington, and on its west side by a back lane running out of the village of Brompton by the buffalo farm.

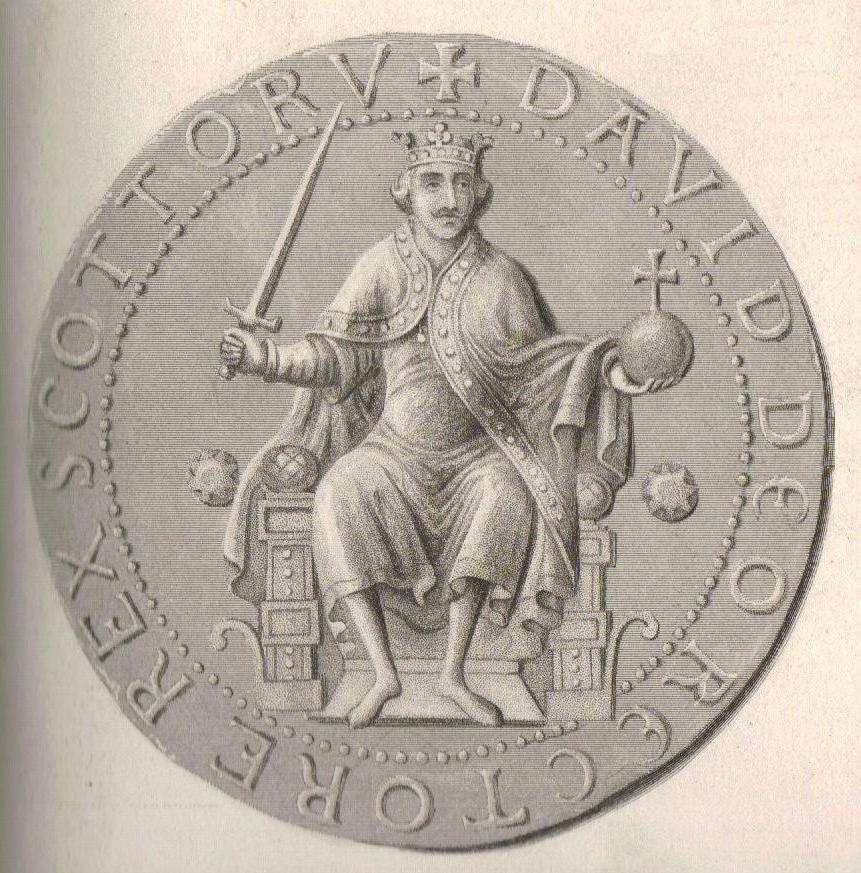

Here, on August 22, 1138, at the Battle of the Standard, an army of about 16,000 Scots, led by King David I, clashed bloodily with about 10,000 Englishmen, fighting on behalf of King Stephen. The Scots were slaughtered and driven back; English losses were light. But when the dust settled, the Scottish king could claim to have been victorious despite his defeat.

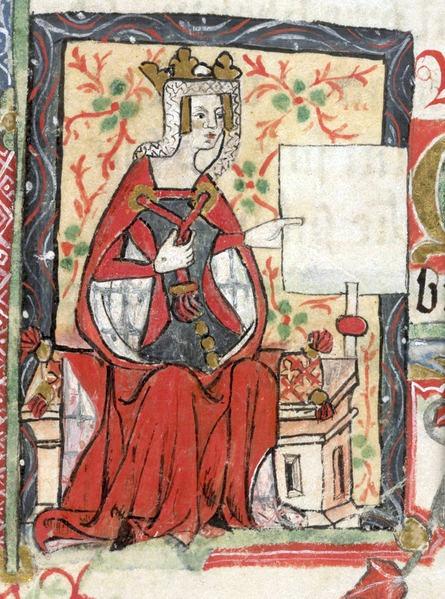

King David had been trying his luck since the English king, Henry I, had died in 1135 without an obvious successor. Stephen, who was the grandson of William the Conqueror, claimed the throne, as did Matilda, who was the Conqueror’s grand-daughter. Matilda was also the niece of David, so the Scottish king regularly raided into England in the hope of pressing her claim and gaining some territory for himself.

In 1138, he brought an army of 26,000 Scots over the border, quickly capturing Northumberland – only the strongholds of Bamburgh, Newcastle and Hexham Abbey held out against him.

Then he crossed the Tyne into Durham. The Scots were, according to one contemporary chronicler, "an execrable army, more atrocious than the pagans, neither fearing God nor regarding man, spread desolation over the whole province and slaughtered everywhere people of either sex, of every age and rank, destroying, pillaging and burning towns, churches and houses".

Useful Durham men and women were captured and sold into slavery; useless ones – pregnant or infirm, young or old – were killed.

Stephen, though, was occupied in southern England where there was rebellion among noblemen in support of Matilda.

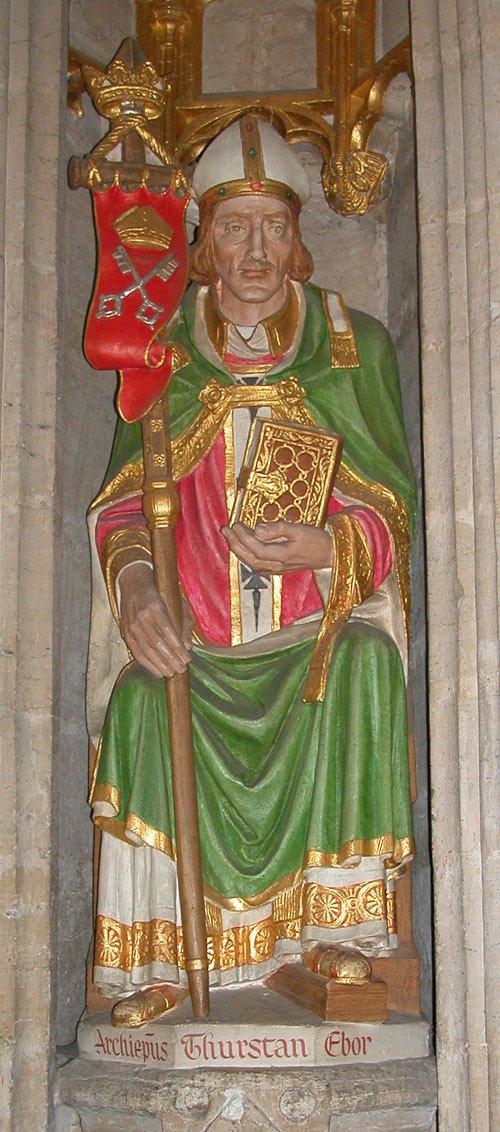

It fell, then, to Thurstan, the Archbishop of York, to raise an army to see off the Scottish invader. He marched his men to Thirsk from where he sent a message to David in Durham, offering to make him the Earl of Northumberland if he returned home peacefully.

David refused, and belligerently crossed the Tees – probably at Neasham – into Yorkshire. The residents of Northallerton fled, fearing that like their Durham neighbours, they would be enslaved – or worse…

Thurstan was nearly 70 and remained in Thirsk as his army marched north into battle, but he had convinced his men that it was a holy war, that they would be doing God’s work if they repelled the devilish Scots. He promised all who made the ultimate sacrifice would have their sins forgiven in the afterlife.

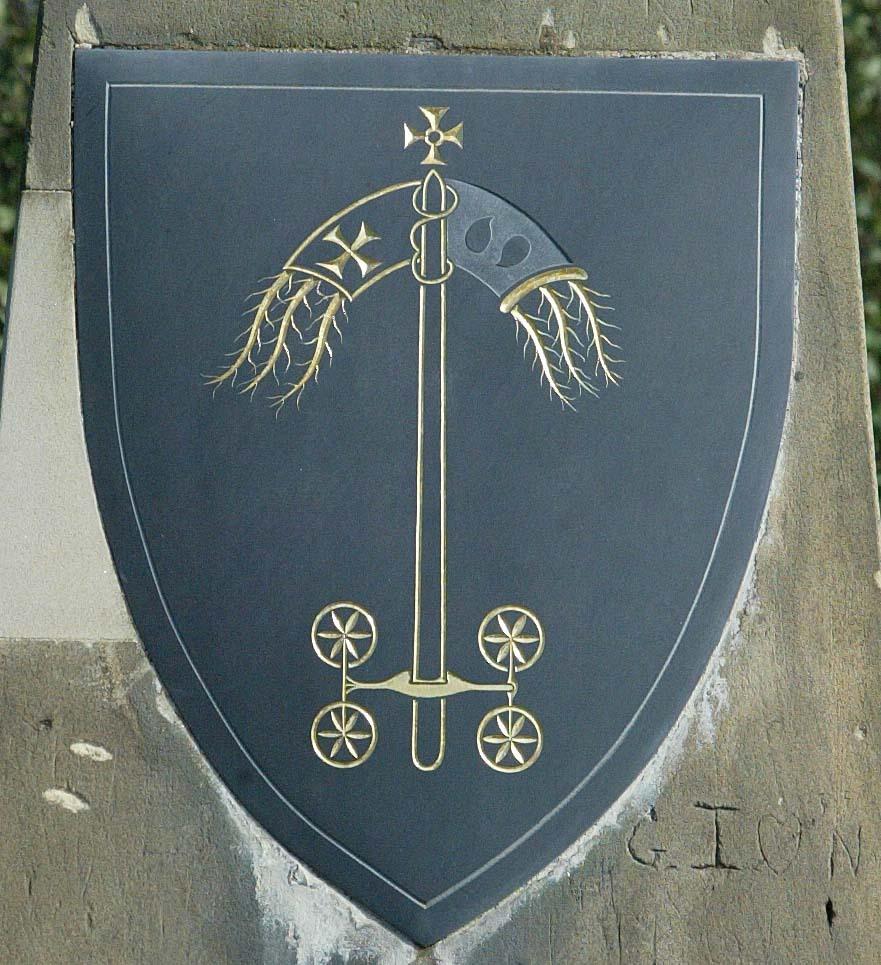

While on the Continent, Thurstan had noticed how armies rallied around flags, or standards, so he had a four-wheeled cart built with a 12 metre high mast on it, to which were attached the consecrated banners of St Peter of York, St John of Beverley and St Wilfrid of Ripon (there is debate about whether St Cuthbert of Durham was represented as Bishop Rufus of Durham had already surrendered to David and probably sat the battle out).

On the top of the mast was a silver pyx, or casket, containing consecrated communion wafers – the English soldiers believed they quite literally had God on their side.

It was the first time that such a device had featured in a conflict in Britain, hence the battle's name.

With their standards flying proudly, the English marched through Brompton and made their stand on a high finger of land, bounded by the two roads with bogs and marshes on either side which would prevent the Scots sneaking round the sides.

(Although the land here today looks dry, farm names suggest this once was a place of carrs and mires. On the east, there’s Leascar, Danger Carr and Fullicar, and on the west, beside the A167, there’s Cinnamire, which was so wet that the Bishop of Durham had a fishpond here until it was drained in the 1740s.)

The Scottish army was about 16,000-strong, as David had had to leave men guarding the places he had captured on his rampage through Durham. They arrived before dawn on the misty morning of August 22, and there was great debate about what David's tactics should be. He eventually allowed the 6,000 men from Galloway, in south-west Scotland, to lead the charge.

It was a costly decision. The Galwegians were as brave and ferocious as Scots can be. They attacked with a knife in one hand and a 12ft spear in the other, and they were described as being “bald and naked”.

The thought of an angry, shaven Scotsman who is not even wearing a kilt to hide his modesty coming at you is indeed frightening, but the description really means that they were naked of armour.

With their banner leading the way – it was a lance with some heather tied to it – they rushed at the English in the hope of getting close enough to use their hand-held weapons.

But just as the Scots’ scruffy banner was clearly inferior to the tall standards of the English, so was their weaponry. The English had longbows and picked off the charging Scotsmen at a distance. Some of the unarmoured Galwegians had so many arrows sticking out of them that they looked like hedgehogs.

“You would see a Galwegian bristling all round with arrows, and nonetheless brandishing his sword, and in blind madness rushing forward now to smite a foe, now to lash the air with useless strokes,” wrote a chronicler.

If a Galloway man survived the arrows, he was slashed to pieces when he reached the firm-standing English line.

Such was the carnage that the Scots were defeated before most of them had even began. Rumour shot round that David himself had been killed, and the Scots began to slope away.

David’s son, Prince Henry, gallantly led a cavalry charge that burst through the English lines on the Brompton side, but there were not enough Scots left to support him, so he, too, had to retreat, leading to a full scale scarper. They “scattered like sheep without a shepherd”, and some of them drowned in the River Tees in their desperation to escape.

The battle lasted less than three hours, and was over by 9am. It is guestimated that 10,000 Scots soldiers and several hundred knights died. About 50 Scottish knights were captured and held for ransom. In comparison, the English lost just one knight, Gilbert de Lacy.

Historians now wonder why the English didn’t press home their advantage and chase after the Scots – perhaps, without Thurstan, they didn’t have the dynamic leadership; perhaps they feared ambush.

So King David, Prince Henry and 19 surviving knights were able to regroup in Carlisle. Despite their defeat, they were never ejected from the country they had invaded.

Despite his victory, King Stephen remained deeply troubled and weak, and when Matilda invaded in the south, he asked the Scots for peace in the north. On April 9, 1139, the Treaty of Durham was signed in which Prince Henry became Earl of Northumberland. Northumberland in those days included the old wapentake of Sadberge, which stretched from Teesdale to Hartlepool (but didn’t include Stockton), and so the Tees effectively became the border between England and Scotland.

Although Bamburgh and Newcastle remained English, and although Prince Henry had to promise to behave himself, David had achieved what he had set out to do on the morning of August 11, 1138. He had successfully extended his territory southwards.

Despite being defeated at the Battle of the Standard, the Scots had won – although the thousands who still lie in the mass graves on the quiet, overgrown country track of Scot Pits Lane may not have thought it so worthwhile.

WITH the help of various local councils, the Northallerton 880 Group is holding a series of events to celebrate the anniversary of the battle:

This weekend: A re-enactment of life in Northallerton in medieval times is held on the site of the former Allertonshire school. This free family event, which runs from 10am to 5pm on Saturday and 10am to 5pm on Sunday, aims to show people what life was like in the town at the time of the battle.

Wednesday, August 22: A three-course medieval banquet is held in All Saints Church – the nave of the church is the only building surviving from the time of the battle, and it was probably used as a hospital to treat injured English soldiers. Tickets are £30, tom include a commemorative pottery beaker, and are available from the eventbrite.co.uk website or by calling

Friday, August 24: Matthew Strickland, professor of medieval history at Glasgow university will give a talk about the battle at 7.30pm in the Forum, Northallerton. Tickets are £5. Book on the Forum website or by calling 01609-776230.

Sunday, August 26: At 3pm outside St Thomas’ Church, Brompton, the Bishop of Whitby will lead in open air, multi-faith remembrance of the battle. The Darlington Salvation Army Band will play, and there will be refreshments afterwards in the Methodist chapel.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here