A WRITER in 1826 gloried in the gory details of the brutal death of Joe the Quilter which shocked the nation.

“They found the body of the murdered man, his grey hairs clotted with blood, his skull discoloured with bruises, his face covered with gashes and, horrible to relate, his throat cut from ear to ear, evidently with a blunt instrument, all gashed and torn, the windpipe severed, the head hanging from the body!” wrote the anonymous scribe of the booklet which told the terrible tale. “Dreadful scene.”

This week, the remote cottage that was the scene of the slaying has been rebuilt at Beamish Museum. It is alongside the replica 1825 railway which transports visitors back to the earliest days of the Stockton & Darlington Railway – and to the moment when Joe the Quilter was murdered on January 3, 1826.

Joe was a good-hearted and elderly artisan, and his story was so awful that numerous penny dreadful authors cashed in on it by producing their own heart-wrenching and punctuation-destroying versions.

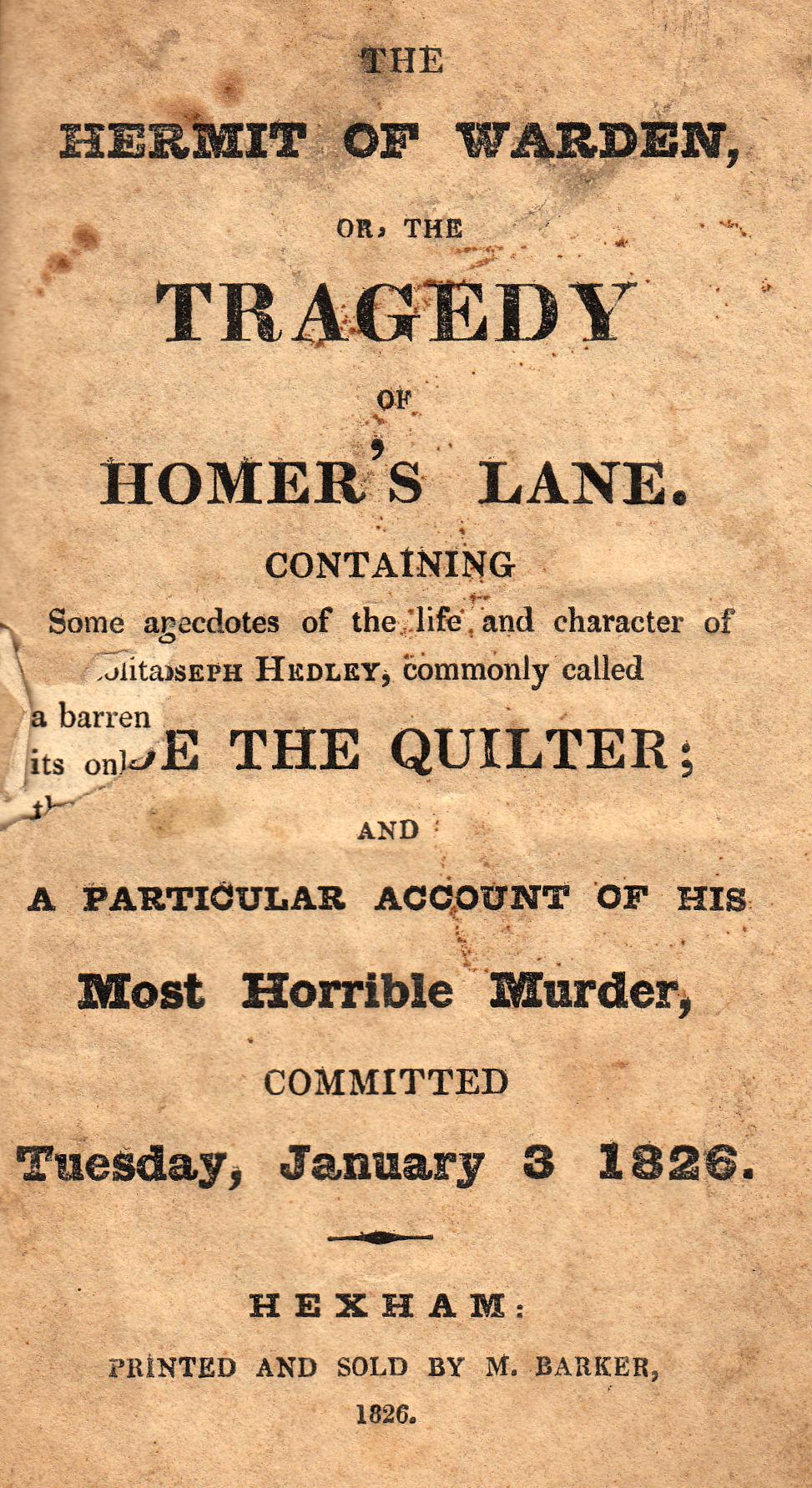

Joan Young, of Darlington, has a battered copy of “a particular account of his most horrible murder” that was published in Hexham practically before poor Joe was laid to rest.

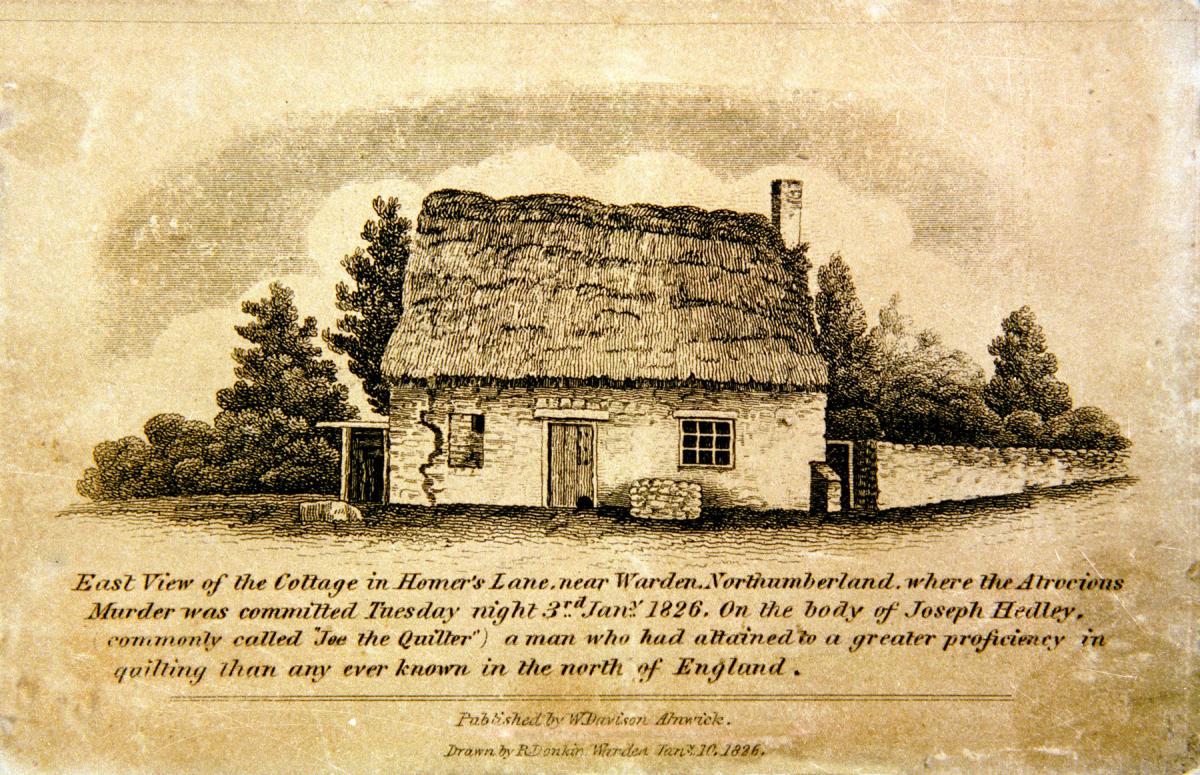

It tells how Joseph Hedley lived in an isolated thatched cottage near Warden which is a hamlet on the north bank of the Tyne close to Hexham, which is on the south bank.

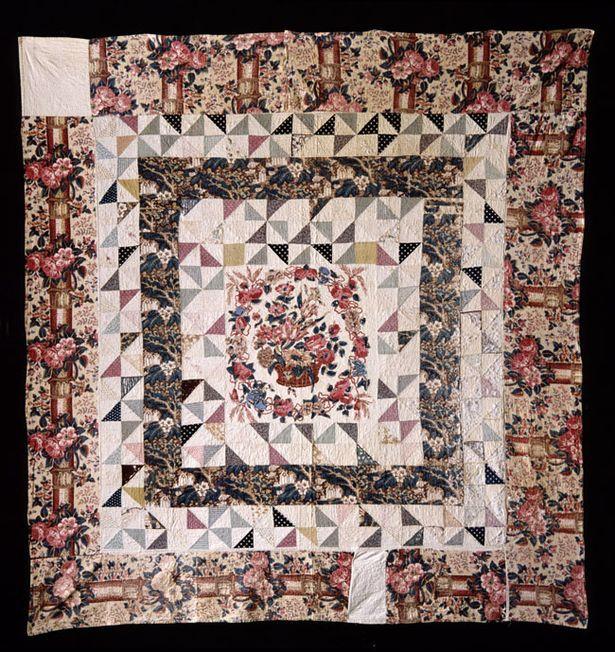

He started out as a tailor, but was so bad that he switched and became renowned as a quilt-maker.

“Hedley the tailor was considered a mere bungler in a common art; Joe the Quilter was admired as most skilful in a profession of extreme difficulty, and of very unfrequent practice,” wrote the balladeer. “He who could neither shape a coat nor sew a seam became distinguished for taste and fancy in the delineation of fruits, flowers and figures.”

His clever quilts were sought after by wealthy customers as far afield as Wales, Ireland and America, although honest Joe had no wish to grow rich by over-charging.

He was dedicated to his wife, who was much older than he, and for eight years he gave up his trade so that he could concentrate on easing her dying days.

“All the duties of the housewife, all the domestic drudgery fell upon poor Joe, and to this continual trial of affection and duty he sacrificed his time – his trade – and the savings of his youth,” said the Hexham writer.

Another poet told of his commitment to his unnamed wife:

He was her housewife, doctor, nurse

But still the poor old soul grew worse

And she was lifted to her hearse

By weeping Joe the Quilter.

By now, Joe was almost destitute – although there were always rumours that this quilter of international renown must surely have a fortune stashed away somewhere in his cottage. His eyes were failing so his quilting days were over, but cheerfully in the growing gloom, he tended his garden, looked after his animals and welcomed the few travellers who passed his cottage door – despite being “extremely feeble and very poor” himself, Joe took in anyone who needed shelter.

(It is said that Joe harboured smugglers at his lonely hut, but our writer doesn’t regard that as a black stain on his principled character.)

On Sunday, January 1, 1826, a traveller spotted Joe at his window reading his bible. On Tuesday, he ventured out to his nearest neighbour, a mile or so away at Warwick Grange, to get some milk for his tea. On Wednesday, a passer-by thought it strange that his clogs were lying outside the door and there was no smoke coming from his chimney. On Friday, a small boy told his elders he’d seen blood smeared on Joe’s front door and, as he hadn’t been seen for four days, a party was sent to the cottage on Saturday.

Our writer gives an impression of the investigation: “The clogs lay still…the house was silent…the door was fast…they knocked…no answer…Joe must be asleep…they pushed it open…all was dark and quiet…Joe must be out…they advance, drawers were open, locks forced…Joe must have been robbed…blood marked the floor and stained the furniture, the curtains were spotted…old Joe must have been murdered!”

And murdered most horribly, his throat bludgeoned with a blunt instrument, his neck all but severed.

“No words could express their feelings: the solitary spot, the ruined cottage, the dark chamber, the butchered man, a spectacle more horrible can hardly be conceived,” wrote the Hexham pamphleteer.

“The hands of the deceased were deeply gashed in attempting to force the knife from his destroyer. Weak as the old man was, he had struggled desperately for life, and monster as the murderer must have been, he had found his bloody task no easy one.”

The investigators secured the property and returned the following day with a constable.

“On Sunday morning, the hens were let out, and measures taken to prevent the cat from preying on the body,” said the writer, rather unnecessarily.

Surgeons counted 40 wounds on the body, any one of which would have killed poor Joe, but still his assailant – “a barbarous fiend” – had inflicted more.

The gory writer said: “The whole country was convulsed with horror at the perpetration of a crime so bloody, of such aggravation and atrocious cruelty, and happily for the country so rare and unexampled. 100 guineas reward was immediately offered for the apprehension of the murder.”

Joe was laid to rest in Warden churchyard on January 10, 1826, and Home Secretary Robert Peel offered a full pardon in the name of the king to any accomplice who might identify the culprit.

Arrests were made, but no murderer was found. Searches were made, but no murder weapon was ever identified, and the silver salt sellers that a wealthy American was rumoured to have given Joe when he would accept no more money for a quilt were never discovered.

The verdict was “Wilful Murder by some person or persons unknown”, and the writer of our penny dreadful concludes his sorry tale by saying: “The jury sat again on Friday the 13th January but nothing more was made out.”

But it is not quite the end of the story. Because of the widespread revulsion and horrified interest, much detail survives of Joe’s demise. Floorplans were made of the cottage showing the location of the body in relation to the fallen clogs, and when the contents of the humble home were auctioned on March 29, 1826, every lot of Joe’s possessions was noted.

His cottage was demolished in 1872, but a couple of years ago archaeologists from Beamish found its foundations. They provided the basis upon which the cottage has been built, and now visitors to the museum are being invited to see if they, after nearly 200 years, can solve the riddle of who was responsible for the most horrible murder of Joe the Quilter.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here