A “hippodromos” in Greece was a venue where equestrian games were played, and “hippodromes” were briefly fashionable in the Edwardian era as a kind of theatre specialising in animal-based entertainment, like a circus. There was usually a water element to it, which is why Darlington’s hippodrome has the distinctive, 64ft tall tower above its main door.

The terrace of houses on the theatre’s site were cleared to enable Parkgate and the new Stonebridge, of 1895, to become a main gateway to Bank Top Station. If you believe in ghosts, the theatre is one of the most haunted buildings in the region. When mediums performed an automatic writing experiment on the stage, the planchette revealed the name “JW Atkinson” – a study of the 1881 census revealed that a John William Atkinson lived in one of the properties cleared for the theatre development.

The first designs for the theatre – initially called the Opera House and Empire – were produced in 1905 by Darlington’s most eminent architect, GG Hoskins. He designed it for a corner plot so he could get lots of firedoors in it, and it was next to the new fire station – theatres had a worrying propensity for burning down.

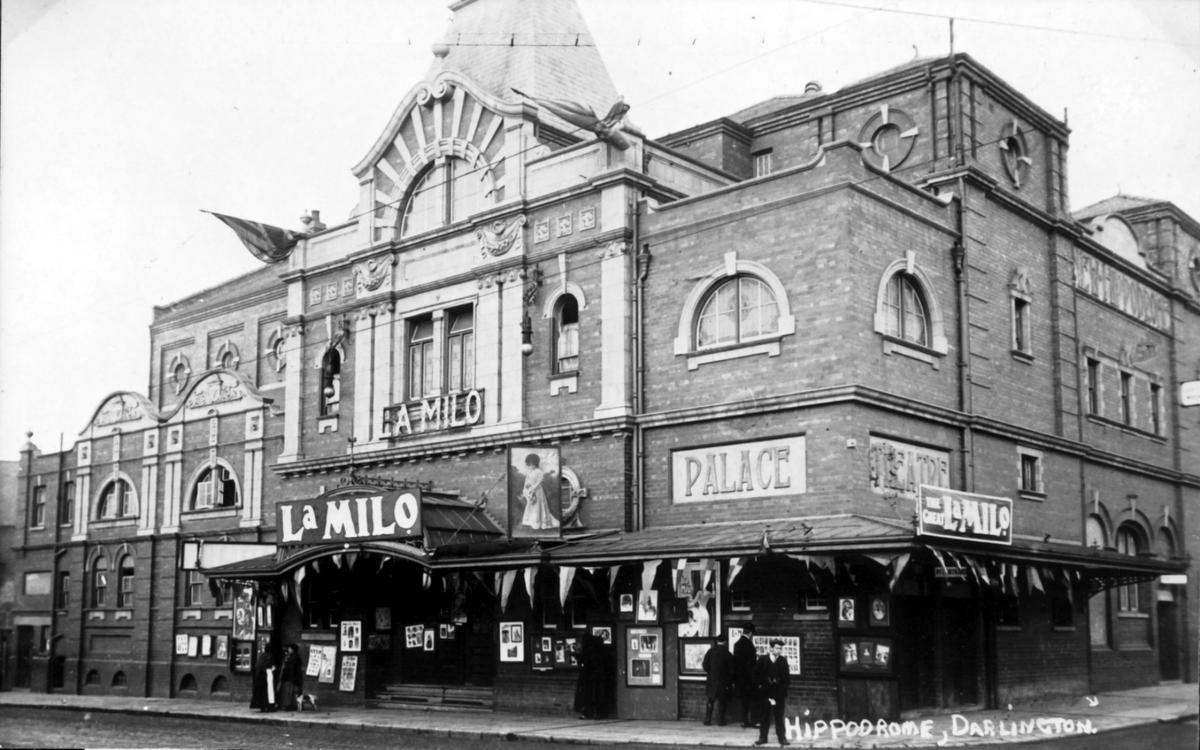

When Hoskins became ill, the project was taken on by George F Ward, a prolific theatre architect based in Birmingham. It is Mr Ward’s glamorous façade that we see today.

It was probably through Mr Ward that Italian impresario Signor Rino Pepi became involved in the project. Pepi, from Florence, had been one of Europe’s greatest quick change artists until he had gone into theatre management. Starting in Barrow, he built up a chain of seven theatres, including ones in Middlesbrough, Bishop Auckland and Shildon. Often accompanied by his wife, Mary, Countess de Rossetti, and her little dog, the diminutive Pepi was a huge character and the lifeforce of the theatre until his death.

Under the grand name of the New Hippodrome and Palace Theatre of Varieties, Pepi’s Darlington theatre opened on Monday, September 2, 1907. Top of the bill was Miss Marie Loftus, “the greatest of all London comediennes”, and more than 4,000 people crammed in to two sittings to see her that night. See how The Northern Echo described the theatre when it had its first look round a couple of days before opening on today’s Page in History.

The acts would travel around the country by train, arriving on a Sunday evening to start their week-long run on Monday. The train that brought them into Darlington also carried the week’s supply of fish from Grimsby for the town’s fish and chip shops. It was known as “the fish and actors special”.

Pepi wasn’t a good businessman – he may have owned a couple of unsuccessful racehorses – and he regularly flirted with bankruptcy. He didn’t mind enticing audiences with a little spice – La Milo was a naked impersonator of statues, and when the scandalously explicit dancer Maud Allan appeared at the Hippodrome in 1918, she was embroiled in the notorious “cult of the clitoris” libel case.

The highlight of the Pepi era was a “flying matinee” by Anna Pavlova, the greatest ballerina of all time. She performed to a starstruck full house on November 17, 1927, finishing with her trademark dying swan. Sadly, Pepi missed the show and died later that evening in his home in Tower Road of cancer of the left lung. He was 55.

Pepi was buried with the countess in Barrow, although the hearse carrying his body over the A66 was delayed by freezing fog which is apparently symbolic of his reluctance to leave Darlington. His ghost was regularly spotted in dressing room number five, which had been his one-bedroom apartment. The current redevelopment has obliterated the dressing room, so Pepi will have to concentrate on his other haunt: the royal box stage right, just a few seconds before curtain up.

A pesky ghost in the theatre is said to be that of Maud Darling, a Darlington-born Edwardian actress (her real name was Olive Watson) who had a connection with Pepi. There’s also a ghost of a Scotsman called Jimmy, a cigar-smoking doorman and a lovelorn girl who jumps from the balcony. During the redevelopment, all manner of new ghosts revealed themselves, perhaps due to the technical difficulties of taking photographs on cameraphones in a building full of shadows.

The second impresario was William McIntyre, a civil engineer recruited from the ranks of the Darlington Operatic Society. But times were changing: films were far more fashionable than live theatre, and McIntyre was forced out in 1932.

Middlesbrough cinema proprietor Julius Reubens took over, and installed a projection box that can still be seen above the words “New Hippodrome” on the Borough Road elevation. It mixed films with live shows.

In 1936, Tyneside impresario Edward J Hinge took over. He claimed to have a knighthood – “Sir Hinge” – and turned the heating on full just before the interval to sell more ice creams. He put on an extraordinary range of shows, from Sadlers Wells Theatre Ballet to Hughie Green, Bobby Thompson and Frankie Vaughan, to Peg Leg Bates who was billed as “the Monoped Dancer” to Paul Raymond’s Soho Review and ecdysiast Phyllis Dixey. If you don't know what an ecdysiast is, she was also billed as “the Queen of the Strippers”.

Teddy Hinge’s era ended in 1957 when he was fined for not paying the theatre employees’ National Insurance contributions. The bankrupt Hippodrome was boarded up and derelict.

Darlington Operatic Society, formed in 1912, was without a venue. Led by Cllr Fred Thompson, it shooed out the pigeons and, with, a small council grant, reopened the theatre on February 26, 1958, on a temporary basis with a new name: the Civic Theatre.

The owners of the building wanted to sell for £8,000 – if not they’d bulldoze the loss-making venue. The council valued the semi-derelict hulk at just £5,500. With the parties £2,500 apart, on November 4, 1961, the Operatic Society bought it for £8,000 and sold it to the council for £5,500, making a massive loss on the deal but saving the theatre.

But the council had plans for redesigning the town centre which didn’t include Parkgate, so it didn’t immediately invest in the theatre. By 1970, its capacity was reduced from 1,121 to a more heatable 601, and when an oil tanker destroyed the elegant Edwardian canopy, it was replaced by an ugly 1960s overhang which was as unsightly as a moustache on the upper lip of an attractive leading lady.

In 1971, the remains of Pepi’s pug dog were found wrapped in a blanket inside a wall – there had been regular reports of children being attacked by a ghostly dog in the nearby stairwell. The remains were sealed under tarmac out the back, and the ghostly dog has never been seen again.

In 1972, council priorities changed, and it appointed 24-year-old Peter Tod as the youngest theatre director in the country. By immersing the theatre in the community, and by basing panto around Christopher Biggins, the star of Porridge, seat occupancy rate at the theatre rose from 20 per cent to 83 per cent in seven years.

On January 30, 1976, ballerina Dame Margot Fonteyn appeared at gala performance.

In 1982, to celebrate the theatre's 75th anniversary, it was suggested for the first time that it should revert to its original name of the "Hippodrome".

In January 1985, Showaddywaddy pulled out of a gig with less than 24 hours notice as lead singer Dave Bartram had been hospitalised when his “eyes were badly injured by an explosion in a garden fire”.

The theatre appears in Channel 4’s most watched programme ever, A Woman of Substance, screened in January 1985 (the recent Great British Bake-Off final is the channel’s second-most watched programme). The theatre appears as a cinema.

By 1989, 98 per cent of seats at the Civic were sold making in the most successful provincial theatre in the country. A £1.5m extension into Borough Road was opened on November 30, 1990, with Dame Vera Lynn performing before 900 paying punters.

Supported by the council’s annual £800,000 arts budget, in the 1990s, the newly enlarged Civic could attract everything from the Royal Shakespeare Company to the Puppetry of the Penis. Big names and big musicals were big attractions, as were panto stars like the Krankies, Linda Lusardi and, of course, from 1998, the Chuckle Brothers.

On October 30, 2010, Darlington council announced that to save £22m from its annual budget, a package of wholesale cuts included selling the theatre or closing it by the following summer.

Whereas the Arts Centre fell victim to the cuts, a £12m plan backed by the Heritage Lottery Fund was put together to enlarge and restore the theatre, and create a children’s theatre in the adjoining old fire station. The Civic shut on May 30, 2016, and yesterday was reborn as the Darlington Hippodrome.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here