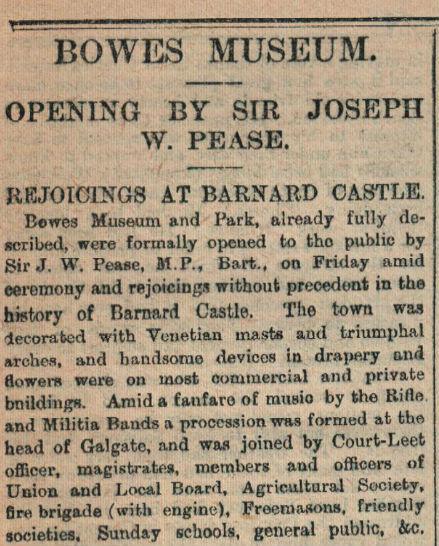

SIR Joseph Whitwell Pease stood in front of the massive, closed doors of what The Northern Echo called, without a hint of exaggeration, “one of the grandest buildings in the world” exactly 125 years ago today.

The time was midday. The sky was leaden. The air was chill.

But a crowd of many hundreds was laid out before him on the terrace of the Bowes Museum, and thousands more were spilling down the sweeping driveways to where the parterre – the symmetrical gardens – would be laid out with the south side of the dale as a backdrop.

"Ever since it became known that the magnificent building was at last to be thrown open, the townspeople have been looking forward to the day when the great doors would swing back, admitting the public to inspect the treasures of art contained within," said the Darlington & Stockton Times.

The museum doors were 17ft tall, weighed eight tons and were typical of the “glories of this supreme temple of wealth and art”: they had been made in Paris by Messieurs Bardin et Fils for about 15,000 francs (about £600) and transported over to be affixed to the French chateau which had been implausibly built in the heart of Teesdale.

And their opening marked the final chapter in the love story of Josephine and John Bowes – who shared a love for each other but also a burning passion for art.

John Bowes was the illegitimate son, and heir, of the 10th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne, of Gibside in north Durham. John served 15 years from 1832 as the Liberal MP for Barnard Castle, his fortune swelling when his horse, Cotherstone, trained at his Streatlam stud near Barnard Castle, won the 1843 Derby with his £21,000 bet riding on it. His winnings, equivalent to £2m today, enabled him to exploit the coal deposits beneath Gibside which, in turn, allowed him to indulge his artistic passions.

He went to Paris, bought a theatre, bought a chateau on the Seine, and, aged 35, fell in love with an actress, Josephine Benoite Coffin-Chevalier, 22, the daughter of a humble clockmaker.

They married in 1852 and began amassing a collection of art, initially to go in their chateau. But in 1860, they sold up and returned to Streatlam Castle with an orangery – yes, literally an orangery, as they transported a number of orange trees in specially-built packing cases by barge to Middlesbrough and then by road to Streatlam, cutting off the branches of trees overhanging what is now the A67 as they went.

They regularly returned to Paris to amass more material – the cross-Channel journeys must have been difficult for Josephine who was petrified of water – which they kept in storage, planning a museum in the French capital.

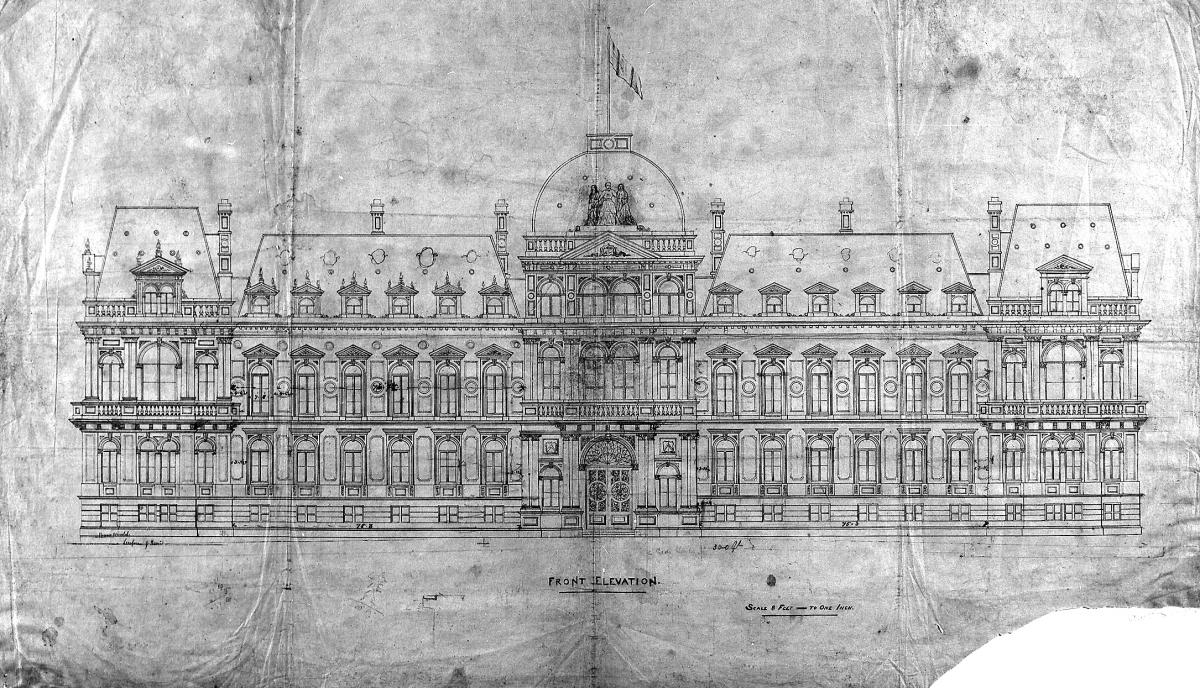

But the late 1860s were tumultuous times in Paris, with the Prussian army surrounding the city – one Prussian shell exploded within 50 yards of their art store. They decided that their collection would be safer in Teesdale, and engaged a Parisian architect, Jules Pellechet, to design a suitably French home for it.

They laid the foundation stone on November 27, 1869. Josephine had badly sprained her foot and rather than lustily plonk the stone in place, she dabbed at it with a silver trowel, saying: “I lay the bottom stone, and you, Mr Bowes, will lay the top stone.”

He is said to have replied: “We’ve seen the first stone laid: God knows who will see the last one.”

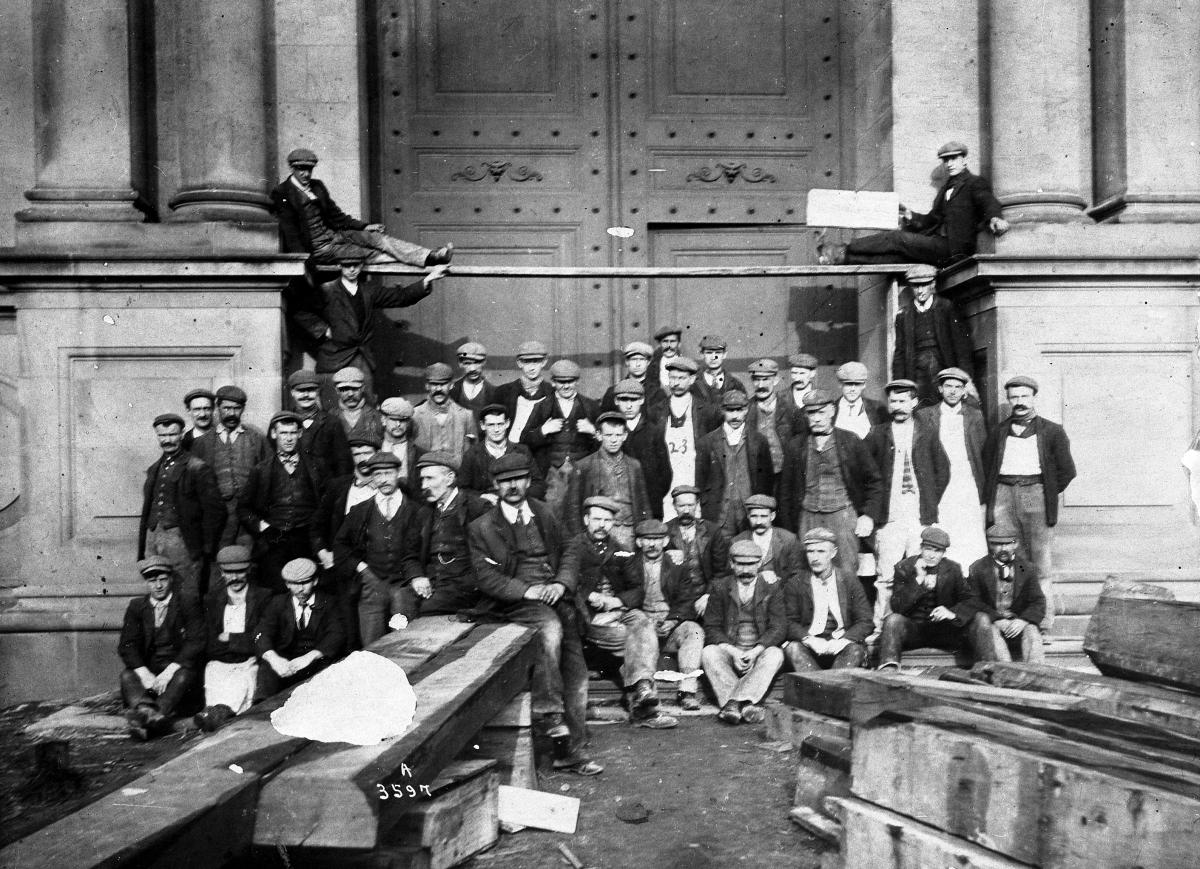

The stone for the exterior came from Dunhouse Quarry near Staindrop; that for the interior came from Stainton Quarry – both on the Bowes estate. With 70 masons going at it hammer and chisels, under the eye of local builder Joseph Kyle, the roof was raised on January 23, 1874, with French and British flags flying above the timberwork.

But on February 9, in Paris, Josephine died of lung problems aged 48 – even in her last days, she had been packaging up treasures to be sent to Teesdale. In her last eight years, she and John had purchased 15,000 items including, for £200, the clockwork silver swan which is their most charming possession.

The work on the museum continued unabated with up to 300 men working on site. It was nearly complete in 1878, but extravagant John began running into money, and woman, problems. He divorced his second wife, Alphonsine, who had been unhelpful to the museum project, after seven years of marriage, and then died, aged 74, on October 9, 1885.

Having spent £165,000 on the construction of the museum (that’s more than £19m in today’s values), he’d left a further £135,000 in a trust to complete the job. But his affairs were “in a state of considerable complication and embarrassment”, which took the trustees years to sort out.

But, 125 years ago today, everything was ready for opening. The D&S reporter arrived on the crowded 10.35am train from Darlington and watched as the large procession formed up in festooned Galgate, and marched off for the museum at 11.30am under the leaden skies.

“There was, however, one consolation: rain did not fall until about 3pm to mar the proceedings,” said the D&S Times.

The Northern Echo said: “The town was decorated with Venetian masts and triumphal arches, and handsome devices in drapery and flowers were on most commercial and private buildings.”

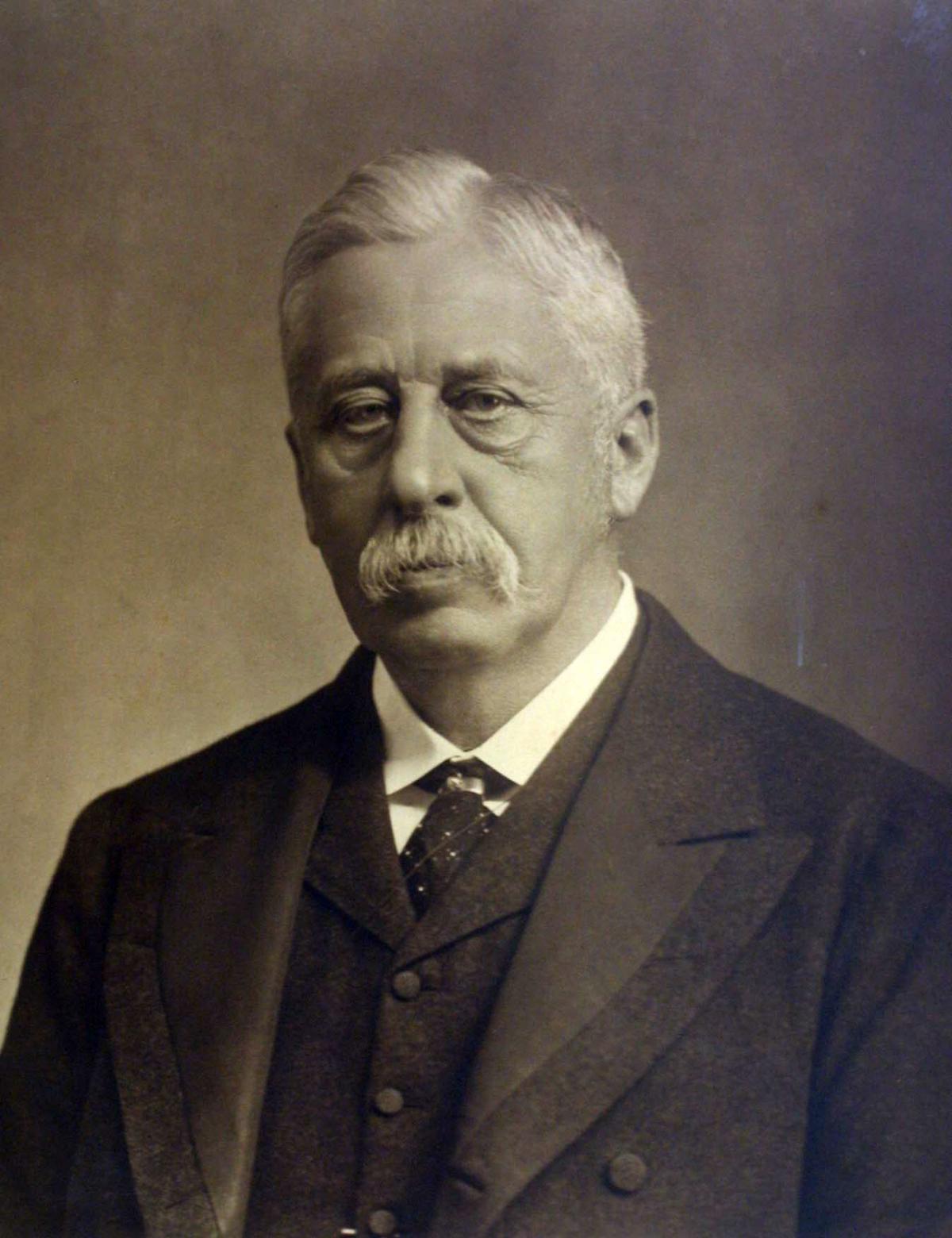

By midday, everyone had reached the museum terrace and Sir Joseph, the Liberal MP for South Durham, began his peroration, which the Echo reported in full.

“My Lord , ladies and gentlemen, I consider that today we have here opened to the public a priceless boon—(hear, hear)—because it is not only the museum that we open, but it ought to be a great centre of education for this district, a centre always and constantly improving in its character and tone, adding another step to those many steps which this country has lately taken in the cause of higher and popular education, leading people's minds from those things that are gross and grovelling and dying to those things which are high in art, which raise up the human mind , which give it employment days when other employment ceases, and when there is much more of that leisure which the working classes are so constantly and so vigorously claiming for themselves (Hear, hear).”

Finally, said the Echo, amid great cheering, “the spectators then flocked into the museum doors, and soon were mounting the grand staircases and gazing with undisguised admiration at the beautiful sights which greeted the eye on every side.”

The principle guests didn’t have long to admire the three storeys of treasures because at 2pm they sat down for lunch at the King’s Head Hotel. In the chair was the 13th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne, but Sir Joseph made another speech in calling for the memory of John and Josephine “to be honoured in solemn silence”.

He said that their memory would live within the museum and that their project “affords an example that if great things are to be done, they require long, constant and persevering labour”. Plus a shed load of money.

And he said: “Their work that day contemplates not only the people of the district but the thousands who might visit the town (cheers).”

He was right – in the first year alone, nearly 63,000 visitors passed through the museum’s grand, Parisian double doors.

SIR JOSEPH WHITWELL PEASE was the son of Joseph Pease whose statue stands on Darlington’s High Row. Sir Joseph, who lived at the opulent Hutton Hall, near Guisborough, headed the family’s coal and ironstone mining operations until his bankruptcy in 1902. He was MP for South Durham from 1865 until the boundaries were redrawn in 1885 when he became MP for Barnard Castle, seeing off the Conservative candidate who was the younger brother of the 14th Earl of Strathmore and a Wimbledon doubles tennis champion. Sir Joseph remained Barney’s MP until his death, in 1903, which was brought on by the collapse of the family business.

JOHN BOWES was born in 1811. His father was the 10th Earl of Strathmore and Kinghorne and his mother was Mary Milner, a beautiful but humble gardener’s daughter from Stainton, near Streatlam. Just 16 hours before the 10th Earl died, he married Mary in an attempt to legitimise his son’s inheritance.

Years of legal wrangling ensued. The outcome was that John could inherit the estates and the fortune, but not the title.

So the 11th Earl was the 10th Earl’s younger brother. The 12th Earl was the 11th Earl’s grandson, and the 13th Earl was the 12th Earl’s younger brother.

The 13th Earl was Claude Bowes-Lyon, and it was he who was guest of honour at the opening of the Bowes Museum in 1892. His son, also Claude, became the 14th Earl in 1904. Young Claude’s ninth child was Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, born in 1900, who would in 1923 marry Prince Albert, the Duke of York who would later be King George VI, and her daughter would become Queen Elizabeth II.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel