You brave lads of Weardale, I pray lend an ear

The account of a battle you quickly shall here,

That was fought by the miners, so well you may ken

By claiming a right to the bonny moor hen.

ON December 7, 1818, there was a bloody uprising by the leadminers of Weardale against the all-powerful Bishop of Durham, and an old flintlock rifle which featured in last week’s Memories is believed to have been involved in the carnage at the Battle of Stanhope.

It occurred as economic depression stalked the land in the years immediately after Britain’s victory over Napoleon in 1815. His defeat at Waterloo brought to an end the 15-year-long Napoleonic Wars, but no military action meant no demand for lead musket balls which meant no work for the leadminers of upper Weardale which meant no food for their families.

So, as their forefathers had done for generations before them, they turned to poaching.

For centuries, Stanhope Park had been stocked with deer, boar and wolves as it was the private hunting ground of the Prince Bishops of Durham – its entrances are recalled in the names of the villages of Westgate and Eastgate. Every autumn the bishops stayed for several weeks to hunt with hawk and hound.

To protect the bishop’s deer, all local dogs had to have three claws removed from their front right foot – this was called “lawing”, which is presumably short for “declawing”.

As well as the animals, there was the birdlife, particularly the “bonny moor hen” – the famous red grouse – of the damp peatlands.

Oh this bonny moor hen, as it plainly appears,

She belonged to their fathers some hundreds of years;

But the miners of Weardale are all valiant men,

They will fight till they die for their bonny moor hen.

Now, the times being hard and provisions being dear,

The miners were starving almost we do hear;

They had nought to depend on, so well you may ken,

But to make what they could of their bonny moor hen.

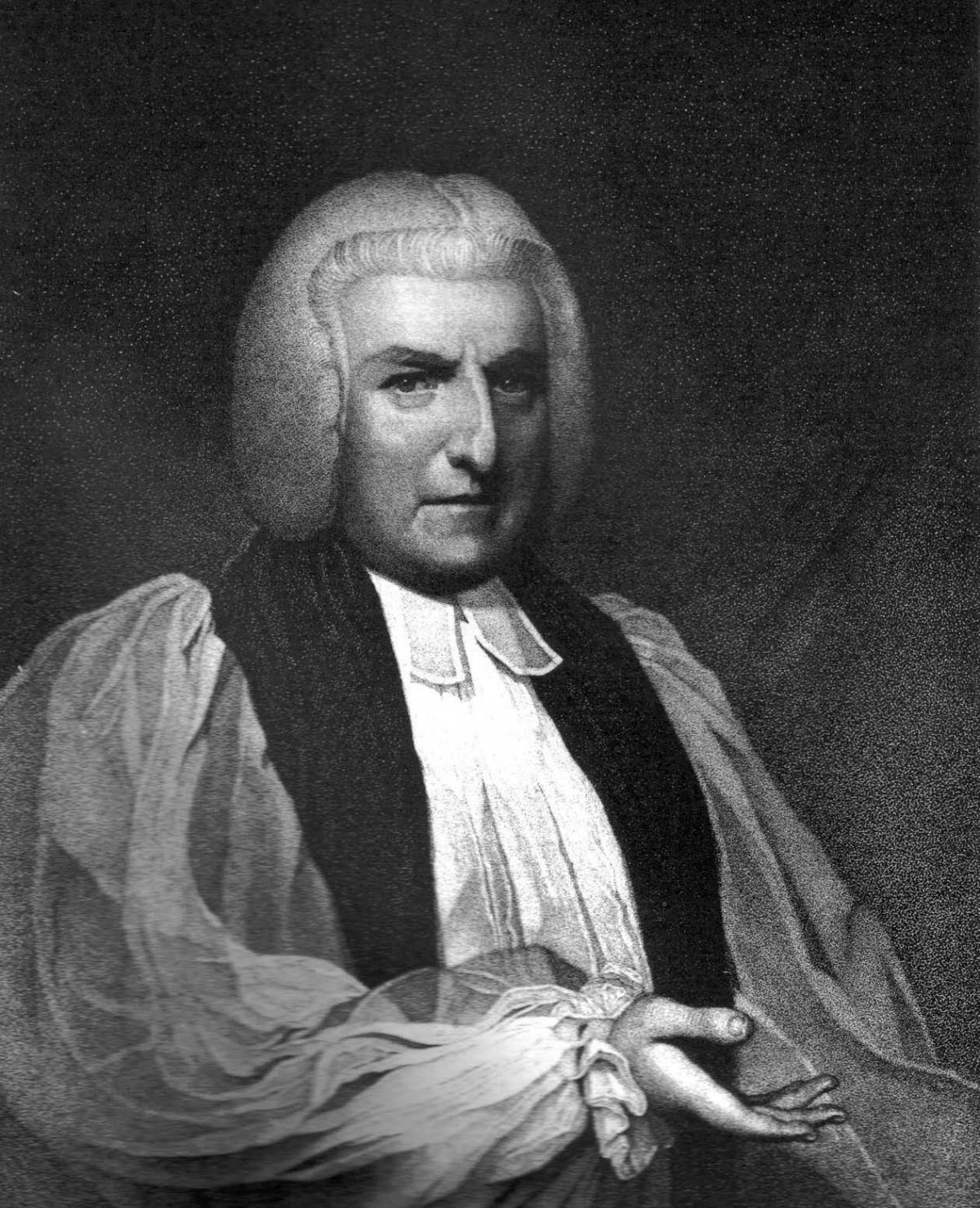

The villain of the piece was Bishop Shute Barrington – “the fat man of Auckland”, according to the poet Thomas Coulson, who was a schoolmaster at Eastgate. He sent his private army up the dale to stop the leadminers poaching his moor hen.

Now, the fat man was an old Etonian. He was the brother of the Secretary of State for War. On New Year’s Day 1812, he had used his army, stationed in Durham Castle, to break up a coalminers’ strike in one of his mines at Chester-le-Street.

However, Barrington was also a philanthropic bishop. At a time when many of the ruling classes believed education of the masses had provoked the French Revolution, he used funding from the sale of his mineral rights to build schools in the upper dale. In Bishop Auckland, in 1810, he founded the Barrington School, which had such a pioneering reputation that it trained teachers to spread its methods into other schools.

Barrington gave land to French Catholic refugees – not his natural bedfellows – who were fleeing their homeland in 1808 to form Ushaw College, and his wife, Jane, once presented every household in a Durham village with a hive of bees.

In fact, Barrington had such a common touch that he is regarded as the first bishop to stop wearing a wig, and it may even be that he turned a blind eye to a few poverty-stricken leadminers poaching a couple of grouse to save their children from starvation.

But with no legitimate income, the miners then understandably took to selling the birds. For the bishop – the fat man – this was going too far, and he ordered that the profitable pilfering should stop.

There's the fat man of Auckland and Durham the same

Lay claim to the moors and likewise the game

They send word to the miners they would have them to ken

They would stop them from shooting the bonny moor hen.

Of these words they were carried to Weardale with speed

Which made the poor miners hang down their heeds

But then sent an answer they would have them to ken

They would fight till they died for their bonny moor hen.

When this answer it came to the gentlemen's ears,

An army was risen, it quickly appears;

Land stewards, bum bailiffs, and game-keepers too,

Were all ordered to Weardale to fight their way through.

The poet says the bishop’s men were led by H Wye of “great Oakland”, who was short and thick-headed, but possessed an “attack dog” which pulled the legs off its enemies. This rag-tag army swept up the dale. They arrested the ringleaders, Charles and Anthony Siddle, of St John’s Chapel, and carried them shackled back towards Durham for trial.

The leadminers armed themselves with pitchfolks and fowling pieces – duck hunting guns – and found a towering leader who was at least six feet tall. They pursued the bishop’s men down the dale, and found them holed up, with their two prisoners, in the Black Bull at Stanhope (now called the Bonny Moor Hen). There all hell was let loose…

Now this battle was fought, fought in Stanhope town,

Where the chimneys did reek and the soot it fell down

Such a battle was never fought in Stanhope before

And I hope such a battle will never be fought more.

For they unhorsed the riders straightway on the plain,

H. Wye and his attack dog in the battle was slain.

Them that ran fastest got pushed out of town

And away they went home with their tails hanging down.

No one was actually killed in the Battle of Stanhope, but one of the bishop’s men lost an eye, and the floor of Black Bull was so flooded with blood that one of the leadminers told the landlady to mix it with meal to make a tasty black pudding.

As the bishop’s men retreated, the Siddle brothers were rescued. Still in their handcuffs, they were taken into Stanhope Market Place where a tinker cut them free, doubtless to noisy rejoicing which would have been followed by boundless consumption of ale.

The partial poet concluded:

Now the bonny moorhen, she's got feathers anew,

Many fine colours, and none of them blue.

The miners of Weardale, they're all gallant men,

They'll fight till they die for their bonny moorhen.

LAST week, our Weardale archive included a 1970 picture from The Northern Echo archives showing two men from the Weardale Association for the Prosecution of Felons. One man is brandishing a rifle; the other is holding some handcuffs.

The Association was formed in 1820, in the days when a victim of crime had to pay to prosecute the felon who had offended against him. The Association allowed all the dalespeople to club together and provide a pool of money to prosecute any felon who needed to be shown the error of his ways.

“It is a great photo of Bill Coulthard and Ken Snaith as it looks as if they have a miscreant in their sights,” writes Simon Edwards of Rookhope. “Bill was a Justice of the Peace and president of the Association from 1968 to 1974, and Ken, who has the handcuffs, was treasurer from 1963 to 1984.”

Mr Snaith died in 1997 although his widow, Mary, still lives in St John’s Chapel where she recently celebrated her 95th birthday, and Mr Coulthard died in 1973, and his daughter, Anne, still lives in Westgate.

Ken Heatherington, of Weardale, said that the picture was taken in the front garden of Mr Coulthard’s home, Daisy Villa in Westgate, with another house, The Elms, in the background. The Elms still stands on the A689 which runs along the dale.

Ken, who is chairman of the Weardale Museum in Ireshopeburn, went on: “The firearm has an interesting history – it is a flintlock “fowling piece” which, according to local tradition, featured in the Battle of Stanhope.”

The gun is still in the dale and it features in the North Pennines Virtual Museum. This is a museum on a website, crammed with fascinating items and stories, and put together by the Weardale Museum in association with the North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Partnership and the Heritage Lottery Fund. You can find it at npvm.org.uk and it is well worth a visit.

IN the archive article, we were a little muddled in St John’s Chapel, and Weardale Councillor John Shuttleworth sent us a photograph to ease our confusion. As a village, St John’s grew up around the medieval chapel, dedicated to St John the Baptist, that served the bishop when he was out hunting. In 1752, the church we see today was built on the site of the chapel, and yet somehow we confused it with the town hall, which was built as recently as 1865.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel