THERE seems to be no word in the English language to describe Kenny Bowen. Everyone knows about philatelists and numismatists, and in Memories we regularly indulge in deltiology – the study and collection of old postcards.

We once got a long-running series out of velologists – people who collect car tax discs – and we are sure John Walker of Stockton, inventor of the friction match, was the first phillumenist – a person who collects matchbooks. We have some sympathy with tegestologists, who collect beermats, although we’d need a big sweetener to be interested in sucrology – the collection of sugar packets from restaurants.

But no one has yet coined a word for Kenny Bowen. Kenny collects bricks. He's a brickologist.

Built into the his walls around his home in Low Etherley, near Bishop Auckland, are hundreds of bricks which tell the story of the Durham coalfield.

For Kenny, building the walls has been something of a brickman's holiday – he has been a bricklayer for 45 years, and got the idea of building his history walls when he was working at Beamish Museum nearly 20 years ago and was asked to build a tramstop out of reclaimed colliery bricks.

The story of the bricks themselves goes back much further to 500 million years ago when the North-East was beneath the shallow Zechstein Sea, bathing in the run-off from the Scottish Highlands. As mud and minerals were washed down the mountains, the sea became a bog with a forest growing out of its rich, wet soil.

Then 280m years ago, the climate changed. The sea dried and the forest died. The trees fell to the floor and formed coal, and the layers of mud and sediment around them turned to different types of rock.

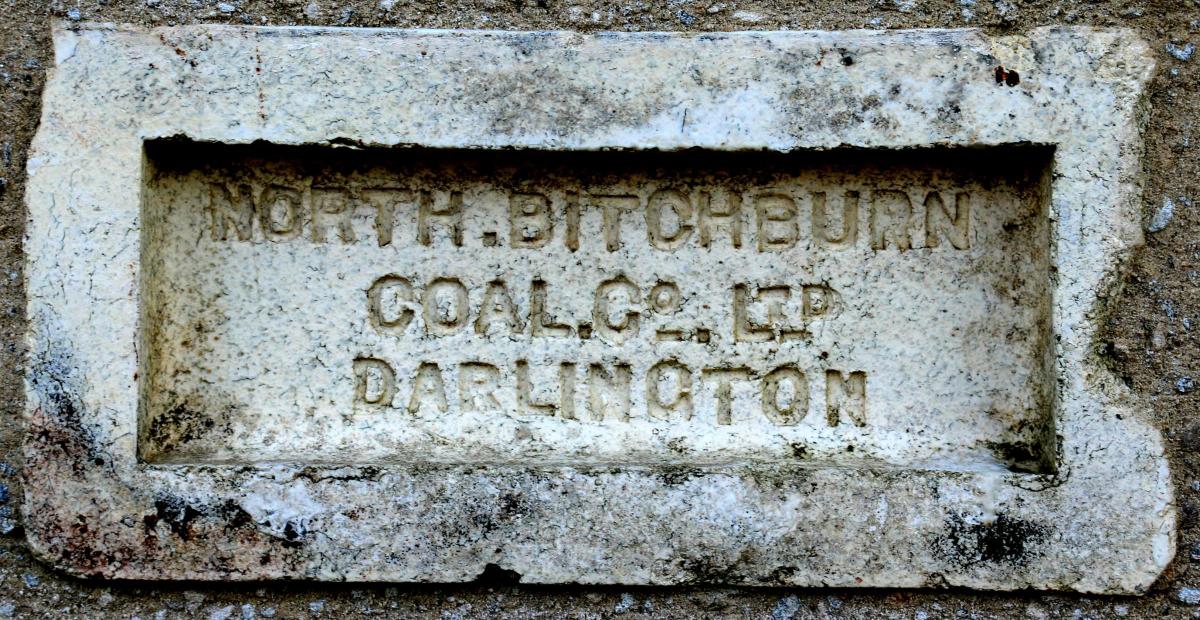

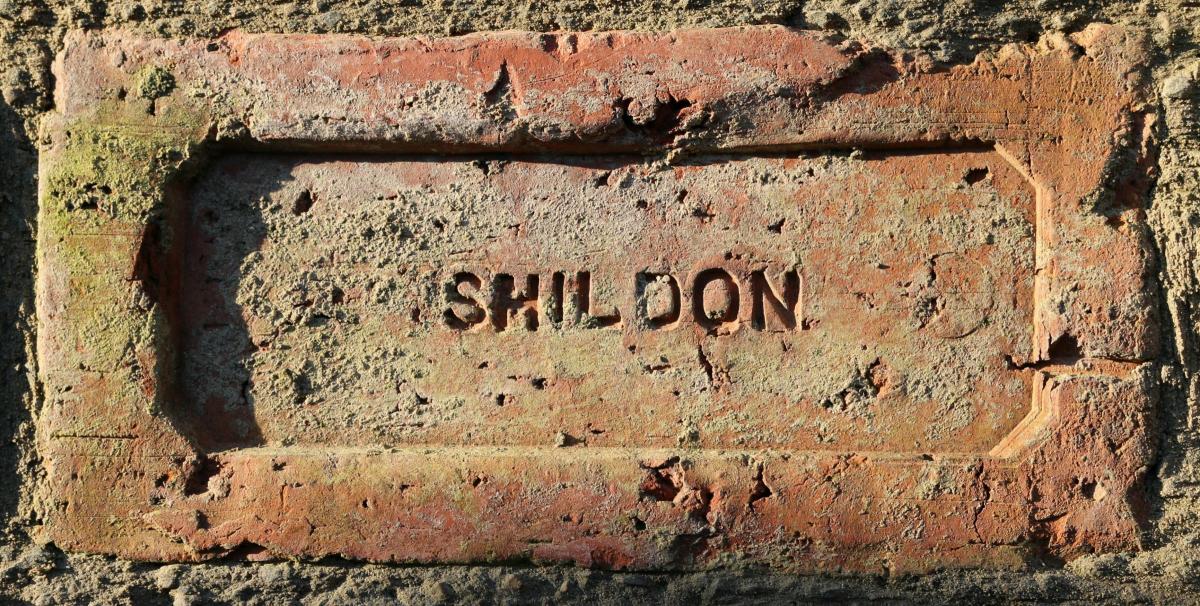

Across the Durham coalfield, the layer immediately beneath the coal became clay – known locally as “seggar”. It was good quality clay – fireclay – and the bricks made from could withstand high temperatures. A local peculiarity was that while most layers of clay produced traditional red bricks, seggar produced creamy, buff-coloured bricks.

As every colliery was mining the layer of coal, most of them also took out the lower layer of clay and made bricks from it. As these were little local enterprises, they pressed the name of the colliery into the brick, or the name of its owner.

So Kenny has a lovely line of Love-related bricks, all connected to the business ventures and partnerships of coal-owner Joseph Love (1796-1875), who has featured, along with the Ferens family, in recent Memories.

Kenny has a wide range of colliery names, from Bearpark to Newton Cap and Randolph, and loads of different companies, from BBCC (Black Boy Coal Company of Eldon) to, of course, the Pease.

Several of his bricks were specially minted, as it were, to commemorate royal jubilees and coronations.

“I don’t go looking for them,” he says. “They just turn up.”

It’s not just names they have on them. Several have pawprints of cats and dogs which wandered across them more than 125 years ago when they were still wet, and one even has the hobnail boot print in it of the small boy who was in the brickyard that day – perhaps he was chasing a stray dog to get it off the drying bricks.

And when you do some proper brickology, all sorts of fascinating stories turn up. Kenny taps an iron hard red brick which says “Accrington nori” on it. Apparently, the brickmaster wanted to boast about how iron hard his bricks were but when the local ironmaster, who owned the blast furnaces, heard that the bricks were to say “Accrington iron” on them, he put his foot down, saying he owned the title of “Accrington iron”. And so the brickmaster quickly reversed the last word, and the Accrington nori – a famous brick among brickophiles – was born.

But can anyone explain another of Kenny’s favourite bricks that just says “TICKLE” on it?

A CALL from pub-supplier Roy Gibbon alerts us to The Loves in Broompark, near Ushaw Moor. Not only does it have this romantic name, he says, but word is that it is made entirely from bricks with “LOVE” stamped on them.

And this may well be correct.

Broompark, to the west of Durham City, grew up to serve the nearby colliery of the same name which we believe was owned by Joseph Love (1796-1875).

Mr Love is a fascinating fellow. He was born extremely poor in County Durham, became an itinerant packman hawking soft goods around the colliery villages. Aged 25, he’d made enough to open a shop; aged 29, he had the good fortune to marry Sarah, the daughter of a prosperous North Shields timber merchant.

In 1840, he bought into his first pit, Brancepeth, and, with partners including the Ferens family of Durham City, he gradually acquired an interest in six pits. He was a devout Methodist but a ruthless businessman, evicting striking miners from his houses.

When he died in 1875 in his house Mount Beulah, in the city, his £1m estate made Sarah, his widow, one of the wealthiest women in the country.

It is understood that the Broompark pub was built in 1896, with bricks from the colliery, and was originally named the Joseph Love Hotel.

THE Penguin Dictionary of Surnames says of Love: “From the Old English first-names Lufua (male) and Lufu (female), meaning “love”, or a nickname for a person bearing some resemblance to a she-wolf, though used in a far-from-derogatory sense.” It is quite widespread in England and Scotland.

DULCIE STOBBS of Shildon continues the love story. “When I was a little girl starting Timothy Hackworth School in 1937, there was a teacher called Miss Love,” she says. “I never heard of the name again until I came across it in your article.”

Could, she wonders, the Loves in her life have been related? Can anyone tell us?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here