IN the days when a golfer only needed a brassie, a baffie, a mashie, a cleek, a niblick and a putter, one of the first links in south Durham was beside the “pellucid waters” of the River Tees in an old quarry at High Coniscliffe.

Michael Heavisides, a printer from Stockton visited the village in 1905 and noted with surprise: "Players, sporting crimson and loud combination blazers, and hats from the Panama to the straw, are idling about or going down to the links for play. . ."

Golf’s popularity exploded in late Victorian England. Railways enabled people to affordably travel into the countryside, and the discovery of gutta percha latex in Malaya enabled the cheap mass production of “gutty” balls.

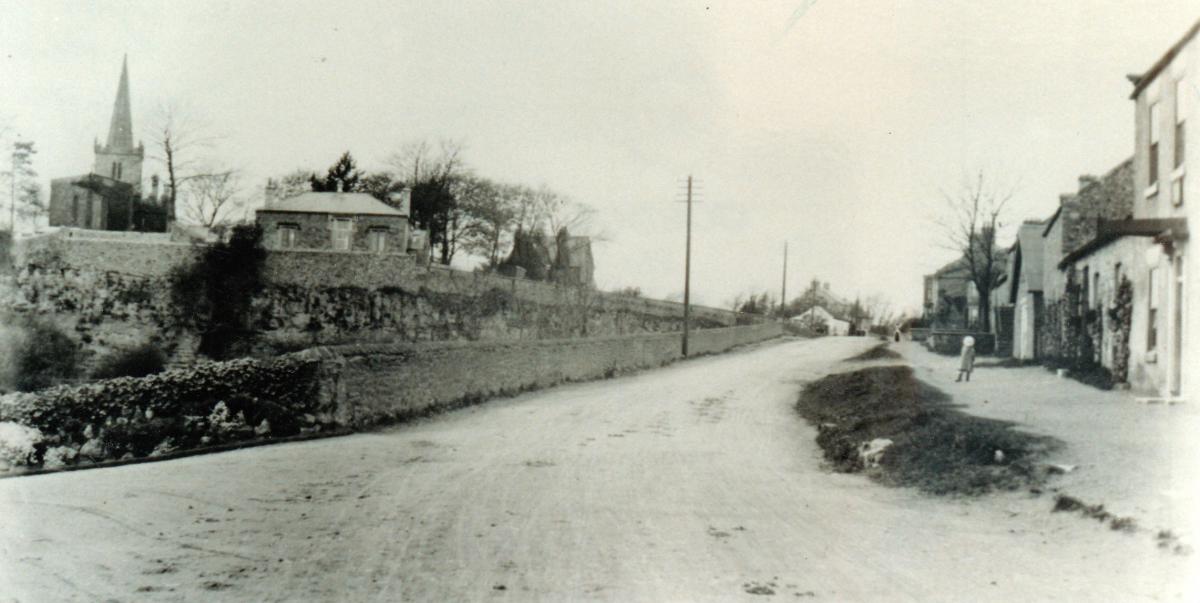

High Coniscliffe – a mile from Piercebridge station to the west of Darlington – was ideally suited for the game. For centuries, agricultural lime had been quarried from the riverbank creating a dramatic rocky cliff on which the vicarage and church perched, and leaving low, gravelly land below. In 1895, a nine-hole links course was laid out on the low land, and a terrace of properties was built overlooking it to act as the clubhouse and the professional’s house.

It would seem that this course was designed by James Kay, who is an important figure in the history of North-East golf. He was a Scot who represented his country and played in 22 Open championships. For 40 years from 1886, he was the professional at Seaton Carew – the oldest club in the region, as it was formed in 1874. He also designed golf courses, including Bishop Auckland in 1894.

The following year, he was at High Coniscliffe, making the most of the unique topography. He placed the first tee high in the vicarage garden – an exhilarating start. The second hole was the longest at 350 yards, and the ninth tee was on the riverbank with the player aiming at a green “which is cunningly placed on a small plateau in the excavated area of the old quarry”.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Mr Kay held the course record – 68 for 18 holes. Most other players sliced their gutties into the Tees.

After his quick round in 1905, Michael Heavisides rather begrudgingly concluded: "The course proves not so easy as some I have passed over – furze bushes, bunkers, wooden obstructions, not forgetting some rather long grass, all tend to bring out the art of the golfer."

However, a more experienced writer for Golf Illustrated spoke in 1904 of how he had been “charmed by the cosy village pubs, by the pellucid waters of the River Tees, the views of the sylvan heights of Richmond, to say nothing of the fresh and invigorating local air”.

The professional at High Coniscliffe was Joe Green, whose wife also knocked up the sandwiches for the clubhouse, which provided “every comfort for the inner man and ample provision for motor cars, cycles, horses and carriages”.

Numerous village lads were engaged as caddies – they charged 1s 6d a day for two rounds – and smaller youngsters made more pennies by fishing lost gutties out of the river. Adults were employed as greenkeepers and grasscutters.

Lord Barnard, of Raby Castle, was the club president; Lord Gainford, of Headlam Hall, liked to play a round, and many of the doctors, solicitors and clergymen of the Darlington area were members.

But nine-holes were not enough. Around 1905, a further nine were laid out behind the village on the fields up to the Barnard Castle branch railway line.

Even so, this didn’t negate High Coni’s greatest difficulty: its location. It was alright for the doctors, solicitors and clergymen. Those that had horses, rode out in their wagonettes; those who motor cars drove out in their Daimlers, Siddeley-Deasys and even Rolls Royces which lined the village’s main street (now the A67) for much of Saturday.

But everyone else had to walk a mile from the nearest station or five miles from Darlington.

Keen golfers were angling for something closer to home. In 1908, the Darlington Town Golf Club opened with nine holes at Harrowgate Hill – the “town” was inserted in the club’s name to differentiate it from the High Coniscliffe course which was calling itself Darlington Golf Club. Within a few years, the Town golfers had moved to Haughton Grange Farm which allowed them 18 holes and which is still the home of Darlington Golf Club.

This sucked away many of High Coni’s members. The First World War delivered the final blow, and High Coniscliffe closed in 1915. A century’s overgrowth has hidden all signs of those days, so it would be fascinating if anyone connected with the village can shed any more light on this pioneering club.

THE story of the golf club was inspired by Keith Walshaw, who was one of many people to get in touch following the spread of Archive photos of Coniscliffe in Memories 307. “My Aunt Bertha used to tell me that she used to go to a golf course there and Sir Vincent Raven used to drive up in an early motor car,” he said. “Where was the golf course?”

Keith’s grandfather, William, was the headmaster of High Coniscliffe village school, which featured prominently in an 1890s photograph. The school, with schoolhouse attached, was built in 1828, and was no more than a large, single classroom – in 1897, William had 84 children on the roll and an average daily attendance of 51.

William was the son of a Sunderland shipwright who came to High Coni in the 1880s, and he remained as headmaster into the 1930s. The school and its smaller neighbour at Low Coniscliffe merged in 1963 on a new site in Ulnaby Lane. Today the primary has more than 100 pupils.

WILLIAM WALSHAW was a wordsmith – he named his children Aubrey, Ashley, Bertha and Betty – and so he would have known that the Tees’ waters really were pellucid. It means transparent or crystal clear, similar to lucid.

THOSE were very different days, but we’ve been struck by how many callers have told us that their experience of the school after Mr Walshaw was not happy.

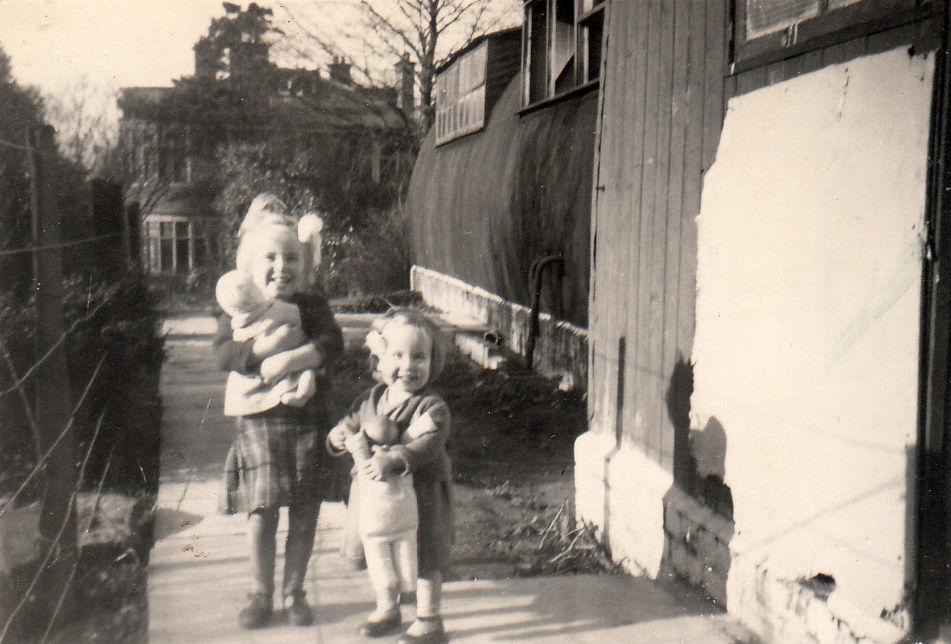

ANOTHER of our Coniscliffe pictures showed two girls standing on the pavement at the eastern entrance to High Coniscliffe in August 1934. Betty Longstaff recognised them as her aunts, Ena and Amy, who grew up with her mother, Nellie, in the cottage behind them.

The Longstaffs outside the cottage which has now been replaced by bungalows at the eastern entrance to High Coniscliffe. Amy and Ena, who feature on the 1934 picture are at either end; Betty is the little girl behind held by her grandfather Jonathan; her mother Nellie is on her right and her grandmother Sarah completes the line up

During the Second World War, Nellie met Ian Clarke, who was a Welshman serving in the South Wales Borderers who were stationed for a while near Winston. They married and after the war, when housing was extremely hard to come by, the two of them and their four girls – Margaret, Betty, Dillis and Dorothy – lived for a couple of years in an ex-Army Nissen hut in the grounds of Coniscliffe Hall.

A Nissen hut is long and semi-cylindrical with a corrugated iron roof. The Clarkes shared their hut with the Towler family – two parents and two children – from whom they were separated by a curtain. Water was via a handpump, and heating was from wood stoves fuelled by wood collected locally. Fortunately, Nellie's mother still lived over the way in the cottage.

Betty and her older sister Margaret with the family Nissen hut on the right and the distinctive rounded wing of Coniscliffe Hall – all that survived the 1945 blaze – in the background

After a couple of years, the family was lucky to get a new council house – prefabricated in West Close, with interior walls of compressed cardboard not strong enough to hang a picture.

Betty has kindly loaned us a couple of old pictures, and she remembers her time in the Nissen hut fondly, surrounded by love, if not bricks and mortar.

IN Victorian times, Coniscliffe Hall was a comfortable country villa, called Valley House because of its position in the old quarry, occupied by prosperous Darlington merchants.

In the 1890s, James Westoll from a Sunderland family of steamship owners, acquired it and began lavishing his fortune on it, adding two large wings and laying out the pleasuregardens.

When he died in 1929, leaving £500,000 (worth about £29m in today’s values according to the Bank of England Inflation Calculator), his widow, Lavinia, remained in the Hall until the Army took it over. They used it as a barracks and a hospital, and members of the Royal Canadian Air Force were often there, perhaps in their time off from frontline duties at the airfields at Croft and Middleton St George.

But the military men – who put Betty’s Nissen hut in the hall grounds – didn’t treat the Westolls' mansion very well, and in 1945, a major blaze gutted the hall and left just one one wall standing.

The fire was apparently set because the servicemen wanted to be billeted somewhere closer to Darlington that didn’t require them to walk for miles.

Today only the gardener’s cottage and stableblock of Coniscliffe Hall remain. The stableblock is a romantic ruin clearly visible from the A67 while the cottage behind it has undergone a wonderful transformation in recent years.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here