Born into a family of fox hunters and horse riders, GAF was a reluctant doctor who became Darlington's best known artist

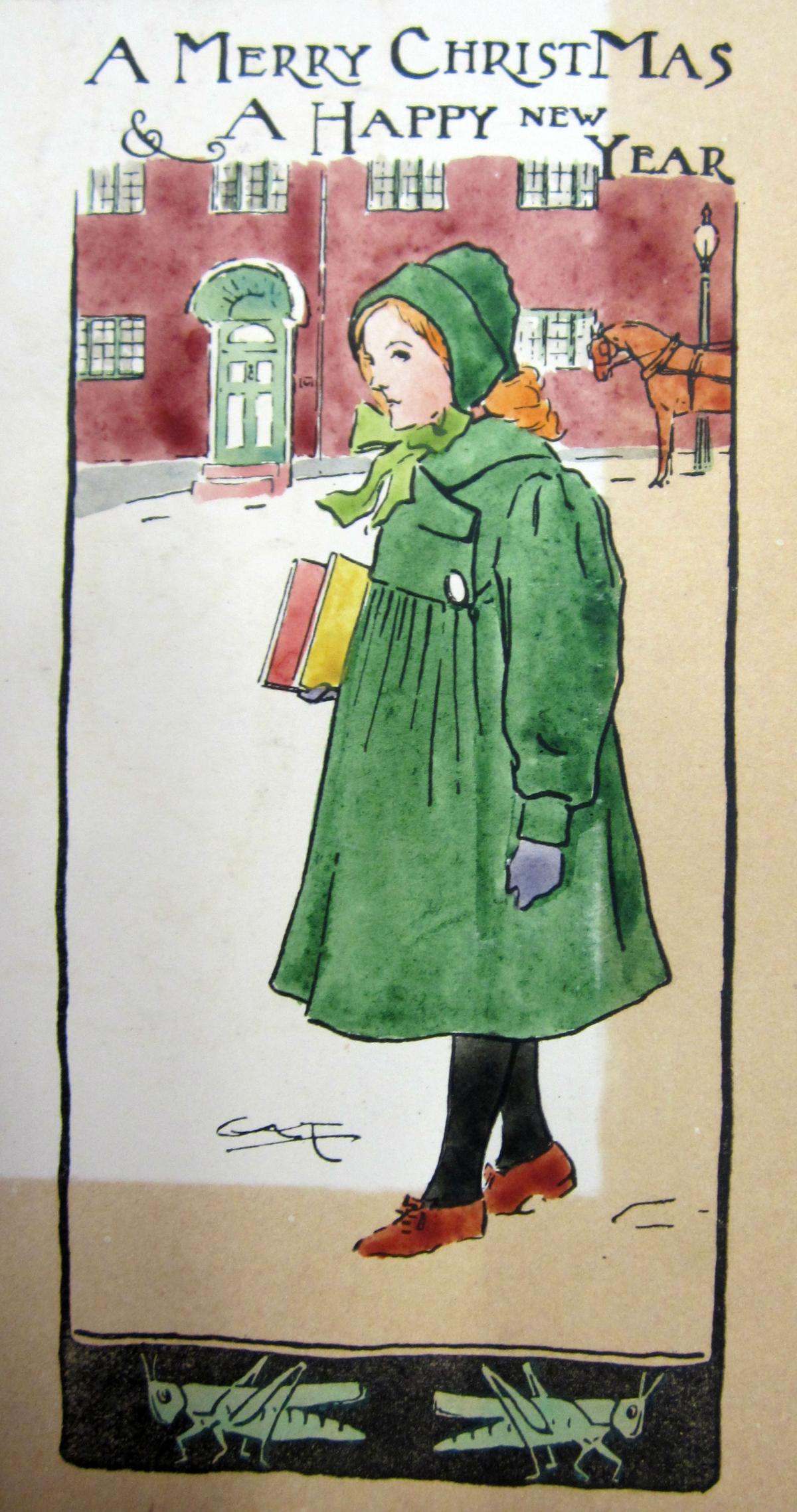

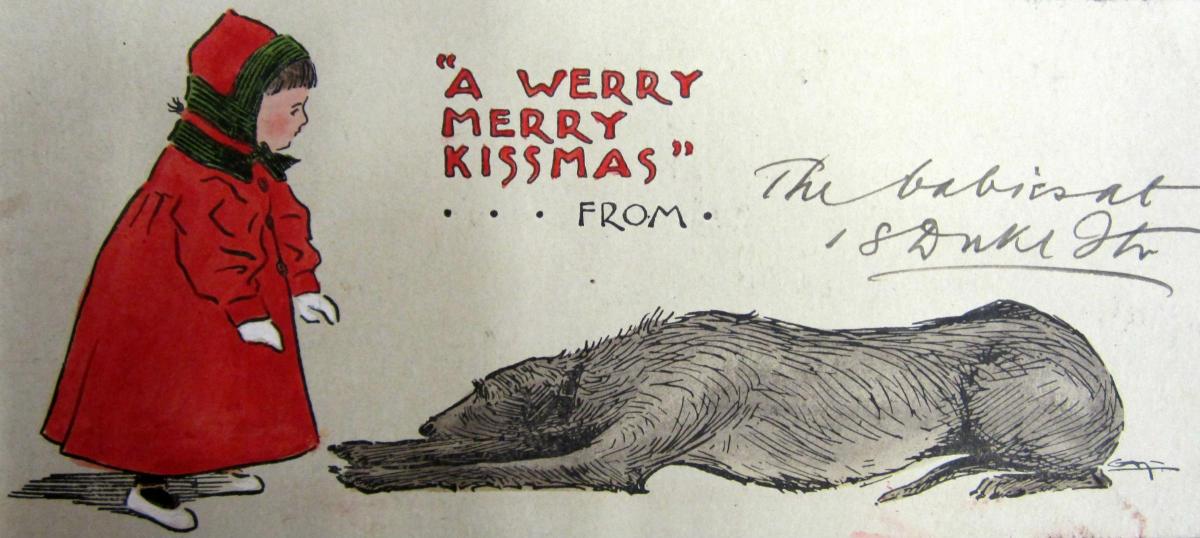

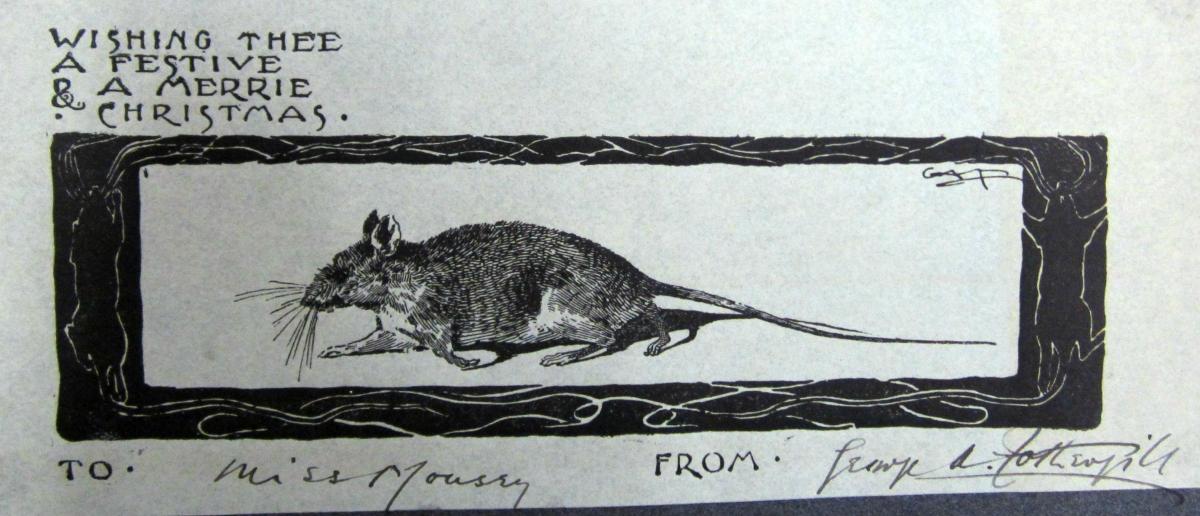

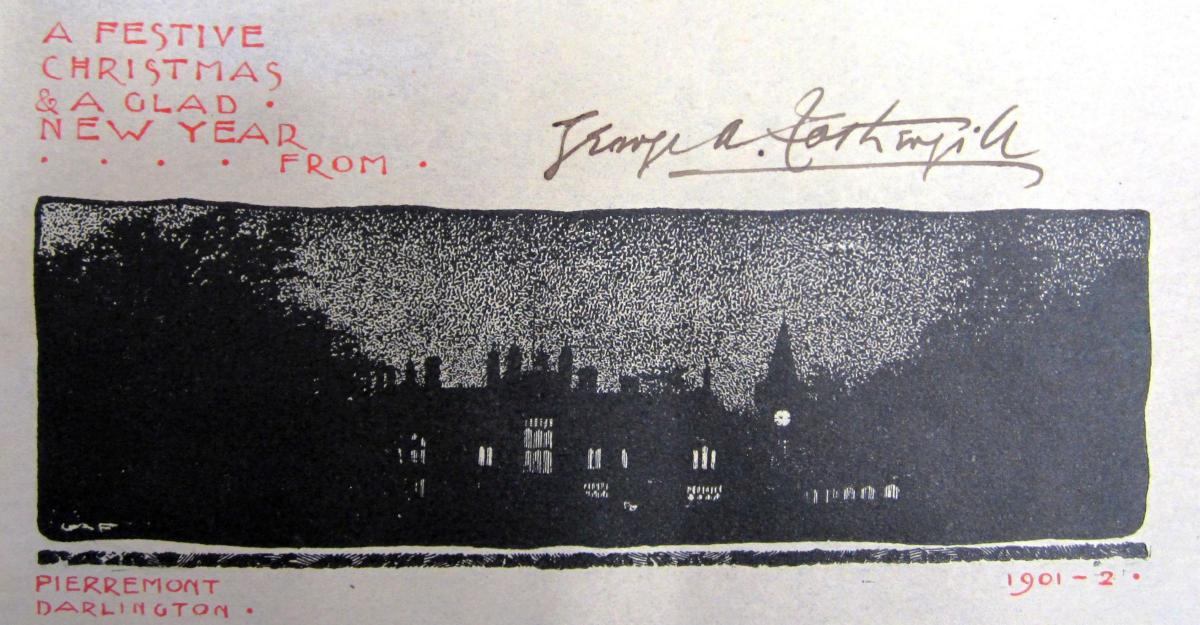

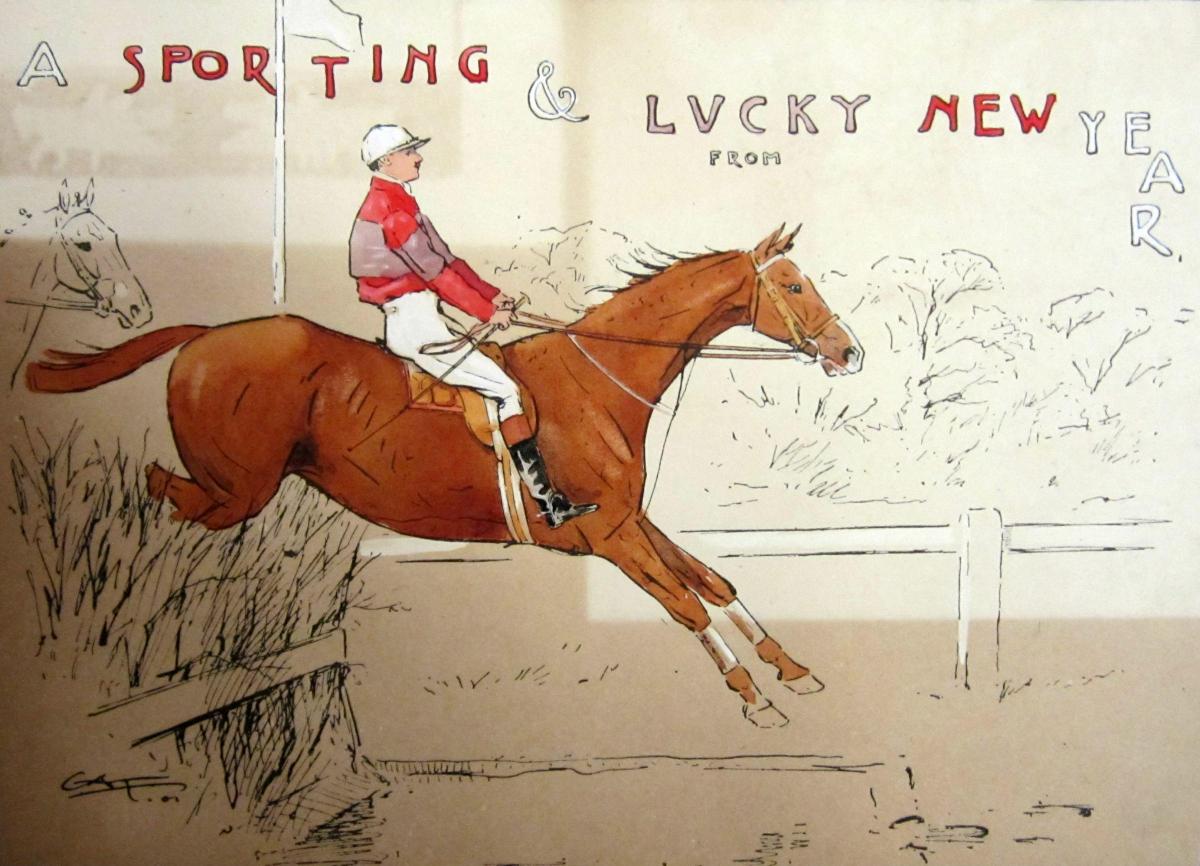

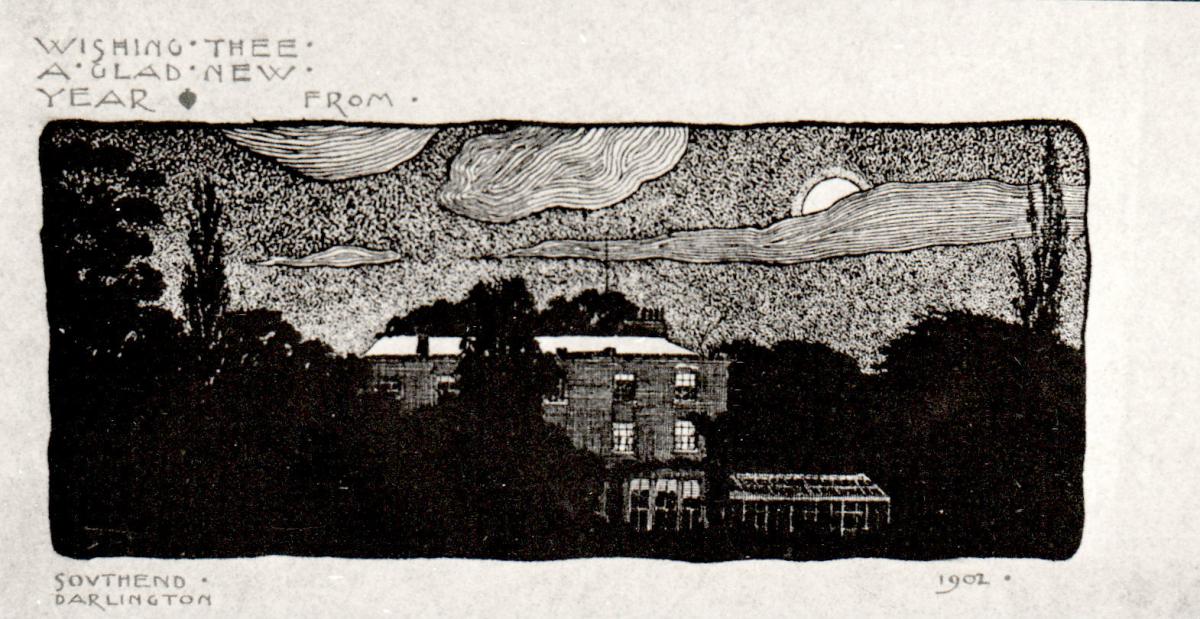

TODAY’S seasonal snowiness from the pen of George Algernon Fothergill and courtesy of Darlington library.

Fothergill – who signed himself GAF – is probably Darlington’s best known artist, and this month’s exhibition in the Darlington Centre for Local Studies features his winter and Christmas scenes.

Fothergill comes across as a man of great passion – a passion for drawing, a passion for horses, and a passion for drawing horses. In fact, in a financial sense he may have been too passionate as after the ten most productive years of his life drawing horses, he was driven out of the town by bankruptcy.

He was born in Leamington near Warwick in 1868 into a family of fox-hunters and horse-riders. He excelled at art at school, but went to Edinburgh University to study practical anatomy with a view to becoming a doctor.

His study of human anatomy only deepened his interest in the working of horses’ anatomy – a local vet lent him dried specimens of legs to draw – and he spent as much time completing artistic commissions as he did doing his studying.

He qualified as a doctor in 1895 – “not quite at a canter” – and he became a locum doctor, although he started each day with a two-hour ride before his surgery. He also exhibited a financial carelessness that would later come back to haunt him: in those pre-NHS days, he made 520 visits in six months for which his patients should have paid him £83 17s but he only received £32. Some were poor patients that he felt uncomfortable charging; others were reluctant payers and he often found something more interesting to do than pursue them.

Because as well as selling his horsey sketches, he was getting his caricatures published in Vanity Fair magazine. Life as an artist seemed more attractive, and potentially more lucrative, than being a doctor so, in 1898, he and his wife, Isabel, moved to Darlington to begin his new career.

At that time, Darlington was one of the great fox-hunting capitals. The 3rd Earl of Darlington, who lived in Raby Castle near Staindrop, had started it off in 1787 by creating the “old Raby Hunt country” which covered nearly all of North Yorkshire and Durham. This patch was so large that he had several packs of hounds conveniently stationed across it and, over time, these developed into separate hunts: the Braes of Derwent near Consett, the South Durham at Sedgefield, the Bedale and his home Raby (which became the Zetland). Plus there were also the Hurworth, Cleveland and Bilsdale hunts.

Some of the large stately homes around Darlington, for example Rockliffe Hall at Hurworth, were taken over by extremely wealthy men who located to the area purely so they could devote their time to hunting. These men also had the means to pay an aspiring artist to capture them in their finery on their favourite hunter.

So Fothergill settled at 18, Duke Street, and produced in 1899, his first publication, An Old Raby Hunt Album, which was sponsored by the Marquis of Zetland at Aske Hall, near Richmond.

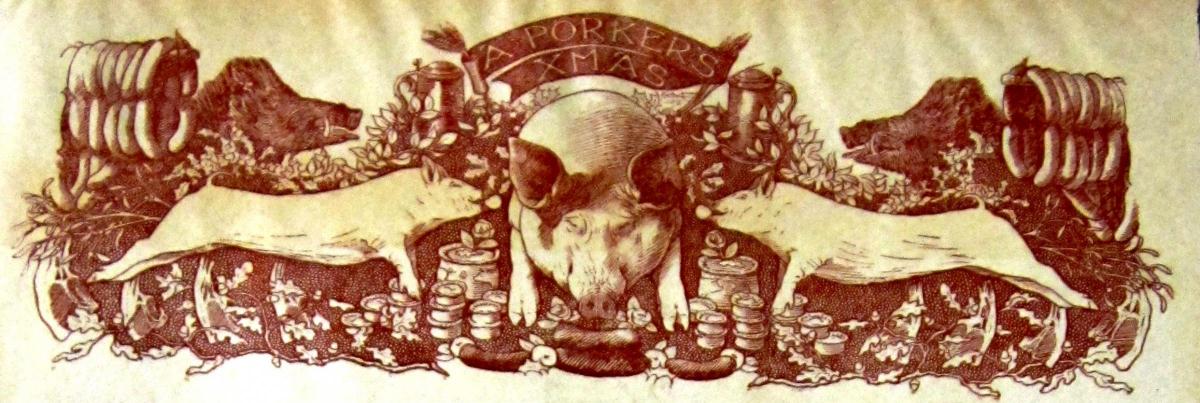

As well as horses, Fothergill had a wonderful eye for amusing incidents which he often accompanied with poetic ditties – The Times in 1903 said his newly-published sketchbook was “a miscellany of clever and vigorous sketches, topographical, sporting and humorous”.

To supplement his hunting income, he designed letterheads, advertisements and Christmas cards, and he produced books of architectural details.

But by 1908, he was £850 in debt (about £100,000 in today’s values, according to the Bank of England Inflation Calculator). The bulk of that was to his publishers, principally William Dresser of Darlington, which was refusing to release 250 copies – half the print run – of his most recent book, Notes from the Diary of a Doctor, Sketch Artist and Sportsman, until he paid off his debts.

He argued that without selling those 250 books (cover price 6s each) he had no income with which to pay those debts. It didn’t wash and he was declared bankrupt at Stockton Court.

He immediately upped sticks, and sought another horsey circle to entertain with his drawings. He fell in with A Charles Schwartz, an American millionaire polo player who, a week before the 1926 Aintree meeting bought an outsider, Jack Horner, that went on to win the Grand National at 25-1. Fothergill immortalised this remarkable achievement with a 34-verse illustrated poem dedicated to his millionaire patron.

Despite the acrimonious departure from Darlington, the local people never forgot him, and in 1940 raised money to buy a collection of his works which was presented to the library – it forms the basis of this month’s exhibition. When he heard, the artist wrote from his home in East Grinstead (which, perhaps coincidentally, is very close to the Lingfield Park racecourse) in Sussex to say how thrilled he was not to be forgotten in the town which inspired him to produce his best works.

Then tragedy struck. On July 9, 1943, the Germans sent 217 Dornier bombers to attack London. One of them got lost and, at 5.05pm, burst through the clouds over Sussex. East Grinstead was below, so it dropped its bombs on the High Street. It circled and then trained its machineguns on the pedestrians before heading for home.

East Grinstead’s population was about 8,000. In those few seconds, 108 of them were killed – many victims were children who had been in the High Street cinema – and 235 of them were seriously injured. Fothergill’s wife, Isabel, 73, and his daughter, Mary, 46, were killed outright, and another daughter, Erica, 49, died of her wounds three days later.

Both girls had been born in Darlington and, like his other two children, had been baptised in St Cuthbert’s Church – indeed, in their childhood they had been pressed into service by their father as models so it may well be them snowballing in the drawing above.

Fothergill himself died 18 months later in his extremely humble home in East Grinstead – but his passion for his art and his animals lives on as these seasonal scenes show.

- The exhibition in Crown Street library runs until the end of the year. With thanks to Mandy Fay and Katherine Williamson

FOTHERGILL drew this to promote Jacques and Jacques' Christmas emporium in Northgate in 1904.

The card is very politically pointed with Father Christmas bringing guns – or "protection" – to Joseph Chamberlain in the chair.

Chamberlain, having resigned from the Government because he opposed Prime Minister Arthur Balfour's free trade policy, had been on a hugely successful national tour advocating the imposition of tariffs on imported goods to protect British industries and jobs from cheap foreign competition.

Mr Jacques hoped the cartoon would lampoon Mr Chamberlain's position which the free traders felt would inevitably lead to war, although in a handwritten note in Darlington library, Fothergill admits that he was always a protectionist and so "was drawing against my own party".

He also says that Ablott, the butler of Duke Street Club, posed as Chamberlain and antique dealer James Wilkinson, of Post House Wynd, played Father Christmas.

The pros and cons of tariffs and trade deals are again in the news following the EU referendum, although no advertiser has yet been brave enough to place a seasonal message in The Northern Echo lampooning either of the sides in the Brexit debate.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here