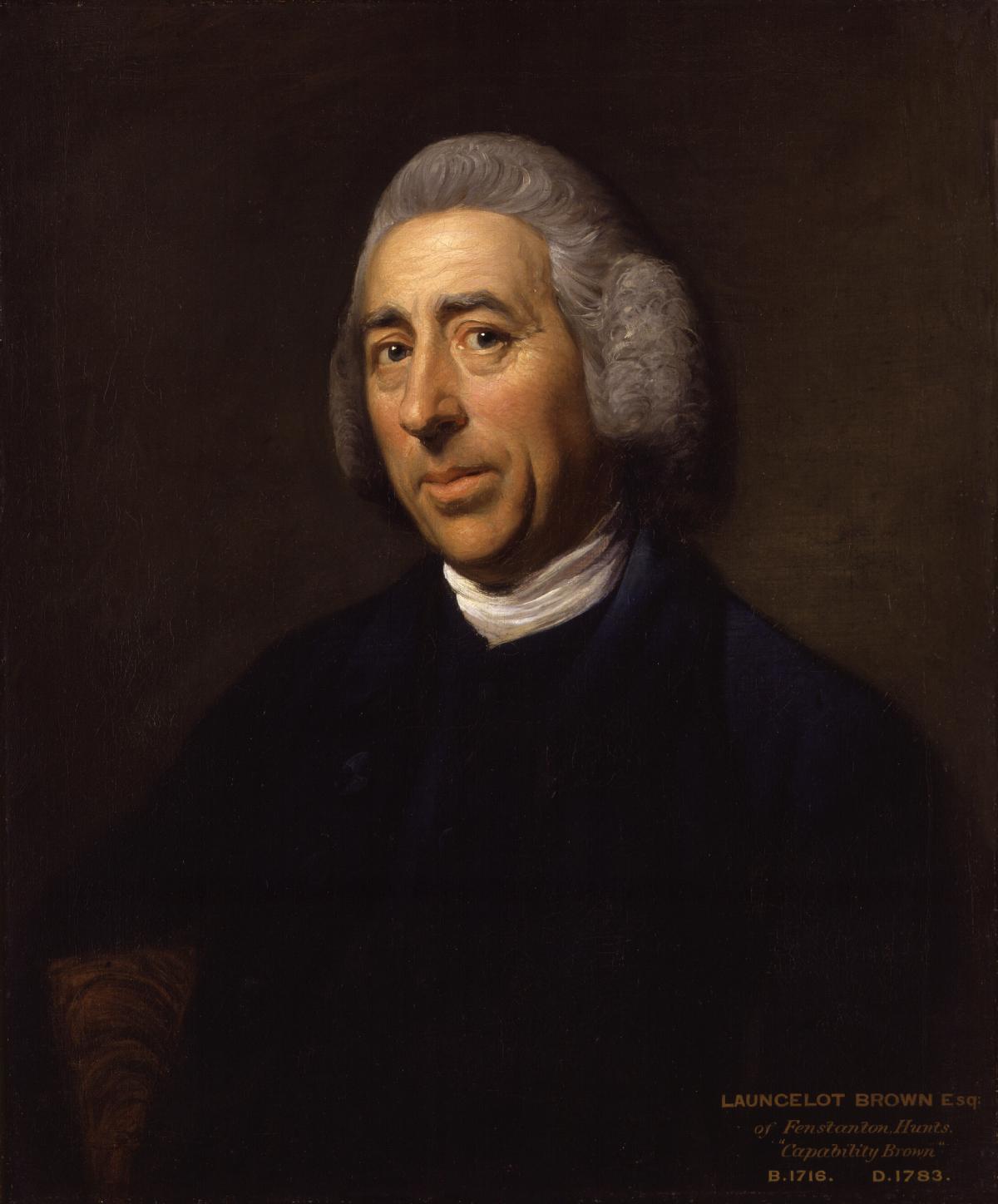

WHEREVER you go in England this summer, you will find stately homes celebrating the 300th anniversary of the birth of one of the most famous of all North-Easterners: Lancelot “Capability” Brown, the greatest of all gardeners.

His birthplace in Northumbria is central to the anniversary, offering throughout August free walks, talks, children’s events, Capability afternoon teas and even a quirky play, The Eyecatcher, from which our picture comes.

He was born in Kirkharle, near Morpeth, in 1716, and walked five miles every day to school in the village of Cambo. His parents worked on the Kirkharle estate for the Loraine family, and Brown started there, too, as a gardener, aged 15.

At the age of 23, he headed south and found fame and fortune designing gardens for the wealthiest landowners.

He dug lakes, sunk roads and buried fences to create shimmering stretches of water and a patchwork of parklands studded with clumps of trees and eyecatching follies and ruins. He worked with Nature to create a more perfect landscape.

Bill Bryson has said: “Brown created landscapes that were in a sense ‘more English’ than the countryside they replaced, and did it on a scale so sweeping and radical that it takes some effort now to imagine just how novel it was.”

He worked on about 170 famous parks: Blenheim Palace, Chatsworth, Highclere Castle, Burghley, Badminton, Harewood House, Longleat, Syon, Stowe, Blenheim…

In our nick of the woods, he worked at Alnwick Castle, Aske Hall near Richmond, and Hornby Castle, between Bedale and Leyburn.

He gained his nickname by telling his patrons that their boggy estates or tired formal gardens had the “capability” for improvement, and it is estimated that over the course of his career, he improved at least half-a-million acres of land. His signature technique was the ha-ha – the sunken fence – which baffled the eye into thinking two separate pieces of land, or even two bodies of water, were in fact one.

And his great skill was to be able to ride around an estate on horseback in an hour and immediately produce a design which combined the natural attributes of the landscape with the landowner’s needs for forestry, agriculture and sport.

He was a millionaire before he was 40, and his career peaked in 1764 when he was appointed Master Gardener at Hampton Court Palace, and he counted the king, George III, and the Prime Minister, William Pitt, among his friends.

Brown died in 1783, and he is regarded as quintessentially English as the paintings of JMW Turner or the poetry of William Wordsworth. In fact, one German admirer has called him the “Shakespeare of gardening”.

About 25 years ago, a plan was discovered at the back of a desk in Kirkharle which showed that in 1770, towards the end of Brown’s career, he returned to the Northumbrian estate of his childhood. Sir William Loraine was planning big improvements, and Brown came up with a radical plan that swept away the right angles and straight lines of the formal gardens that he had grown up among. He replaced them with a serpentine lake flowing through hay meadows.

Sir William didn’t have the funds to implement all the plans, and in 1813, the family became bankrupt when a business venture in Newcastle collapsed. Their Kirkharle Hall, which they had owned since the 15th Century, was pulled down and their estate was asset stripped.

As well as the 13th Century church which gives the settlement its name, a courtyard and the servants’ wing still survive. These house a coffee shop and an assortment of arts and crafts shops and studios, plus they will be hosting the Northumbrian events celebrating the 300th anniversary, culminating in a festival over the August Bank Holiday weekend.

The free walks, talks and events are repeated every Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday throughout the month, and The Eyecatcher play, which is an introduction to the life, times and gardens of Capability Brown, is performed twice daily every Saturday and Wednesday, starting today, until August 20.

For full details, go to stuartsmitheringale.co.uk/kirkharle/

EXACTLY 100 years ago this weekend, two brave local soldiers – one a VC, the other a MC – were killed in the same trench on the Somme.

The first to die was Lt George Butterworth of the 8th Battalion of the Durham Light Infantry, who was the most promising composer of his generation. Butterworth (not Butterfield, whom we met earlier in Memories) was the son of the York-based manager of the North Eastern Railway. He was educated at Eton and Oxford and had come to prominence before the war with his composition The Banks of Green Willow and for setting AE Housman’s Shropshire Lad poems to music.

In the trenches, leading the Durham miners, he was extremely brave. On July 17, near Pozieres, he was slightly wounded leading a successful DLI raid for which he was awarded the Military Cross.

In his honour, his men dug the “Butterworth Trench” from which, on August 4, they launched an attack on the German positions known as “Munster Alley”.

It was initially successful, but on August 5, Butterworth, 31, was killed by a sniper.

The Germans counter-attacked, and so on August 6, Pte William Short of the 8th Battalion of the Yorkshire Regiment (the Green Howards) found himself under a rain of fire at Munster Alley.

Short, 32, was from Eston, and had worked on the cranes in the Bolckow and Vaughan steelworks since he was 16.

Exactly 100 years ago today, he refused to retreat and even when he was severely wounded in the foot, he continued to throw his bombs.

Then his leg was shattered by a shell. Unable to stand, he lay in the trench, adjusting the detonators and straightening the pins of bombs for his fellows to throw, until he died. For this he was awarded the Victoria Cross.

Of course, neither man was able to collect their award – Short’s father went to Buckingham Palace to collect it on his behalf.

Short is buried in Contalmaison cemetery but, due to the ferocity of the fighting, Butterworth’s body was never knowingly recovered – although he may be among the unknown soldiers buried in Pozieres.

Because of this, his most famous composition, The Banks of Green Willows, which has been played on BBC Radio 3 this week, is regarded as the anthem for those lost men.

IN 1939, Darlington had more cinema seats per head of population than any other town in the country. In view of the opening of Vue, in recent weeks we’ve been running through all of the town’s seven purpose-built cinemas, plus the five or six other film-showing halls, which came to a crescendo with the opening of the Regent in Cobden Street on June 5, 1939.

But Darlington’s record was short-lived. The first to close was the Central Palace in Central Hall which had been where the very first flickering movies had been shown back in 1896, and which had screened the first talkies back in June 1927.

Yet come the Second World War, the hulking hall – also known as the Lopey Opera due to its flea infestations – was being outclassed by the modern supercinemas.

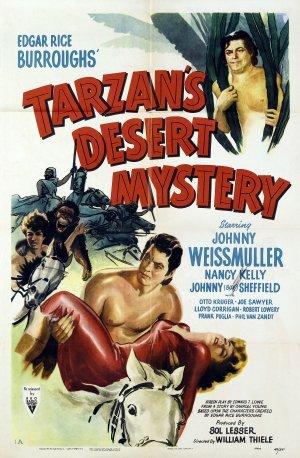

It closed on March 30, 1946, with a showing of Tarzan's Desert Mystery, starring Johnny Weismuller.

Its departure took 700 cinema seats out of Darlington. Its balcony and projection box were removed, and it went back to being an assembly hall.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here