The pub landlord who won a bag full of trophies and medals on the track, raced a dog, and now lies in a war grave in Belgium

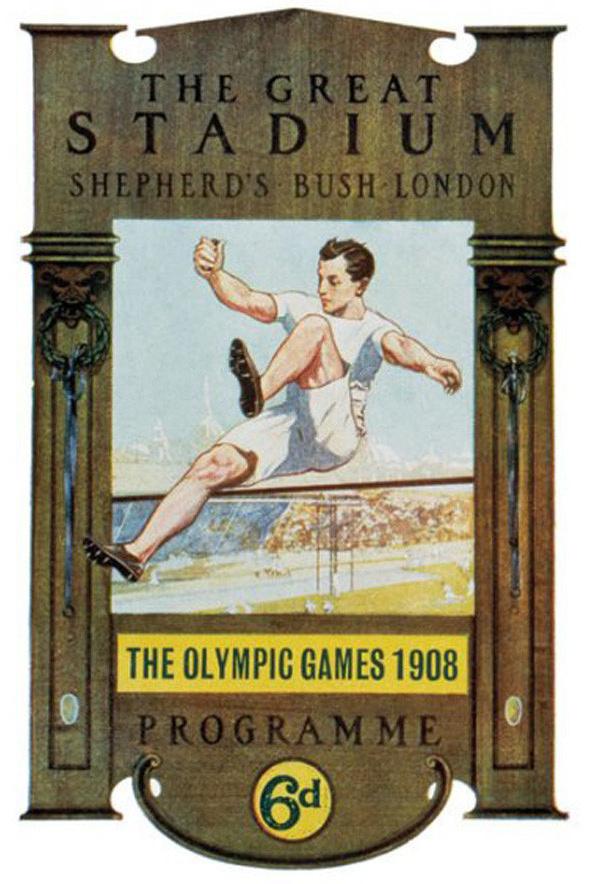

THE British went into the first day of the 1908 Olympics in confident mood.

They had stepped in to save the 4th Olympiad in 1906 when the Italian hosts had been forced to give the games up due to the devastating eruption of Mount Vesuvius, and they had whistled up the 68,000-seater White City Stadium in London so it was ready for the king to declare the games open on July 13.

The prospect of that first afternoon’s events increased Britain’s confidence: the heats of the 1,500 metres. The glamorous event had attracted a strong field from around the world, but Britain’s runners seemed strongest, led by George Butterfield – the thrice British champion, the fastest man in the world over a mile, the Darlington harrier who was quicker even than a speeding greyhound.

The weather, though, put a dampener on proceedings with heavy rain, which meant the uncovered stadium was only a third full for the opening ceremony, and The Northern Echo said the “athletes risked chills and colds by parading on the soaked turf” behind their national flags. Perhaps it was an omen…

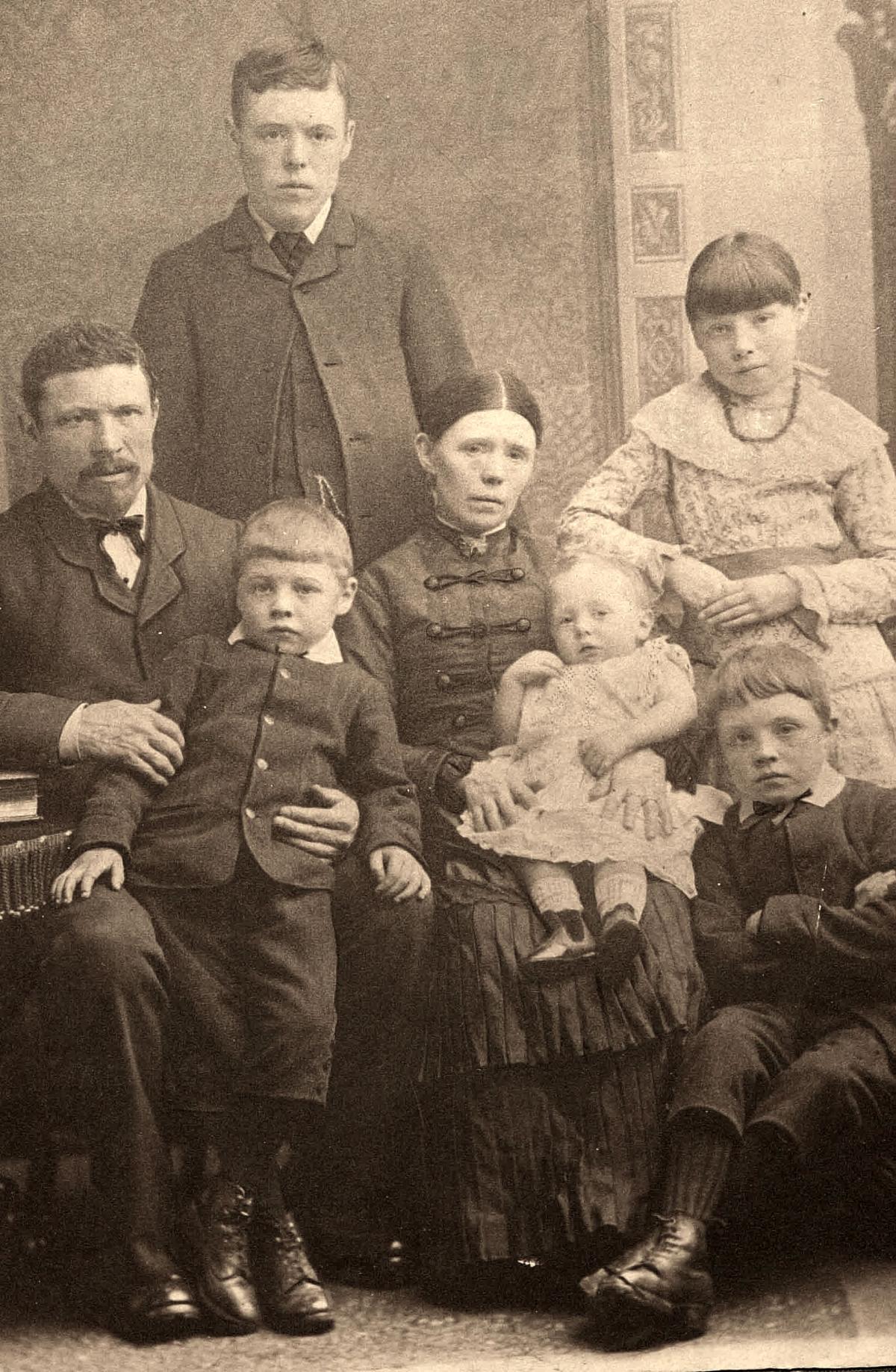

Butterfield, though, was worth pinning a nation’s hopes on. He was born in Stockton in 1879, where his father, Isaac, was a blacksmith, but he based himself in Darlington to train with the Harriers – as Memories 286 told, the club is celebrating its 150th anniversary this year.

He could tackle any distance: in 1904, after establishing himself as the North-East’s top athlete, he took on Alf Shrubb for the national ten mile championship. Alf was at the peak of his powers, unbeatable even by the teams of relay runners he took on for cash, and was regarded as “the idol of the athletic world”.

But “Butt” – as George was known – pushed him very close, losing by only a yard, but announcing himself on the national stage.

The following year, at the amateur championships at the Stamford Bridge stadium, Butterfield was better than the field, winning the mile. The following year, he retained his title in a personal best of 4:18.6 – the fastest mile in the world that year – and he kept hold of his crown in 1907.

Seeking a greater challenge, he took on a racing dog – “among his numerous exploits may be mentioned a race with a greyhound,” said the Evening Despatch in 1917, “which he beat” – and then sailed for Sweden. On his first day in Gothenburg, he won the 100m, 400m and 1,500m races, moving on to Stockholm the next day to win the same distances.

He returned home with a bag full of cups, medals and trophies, and the British Olympic committee asked him to run for the country at the Olympics, making him the first Darlingtonian Olympian, certainly on the track.

On the opening day in 1908, competitors from 18 nations risked catching a cold by parading their flags in the pouring rain in front of the King Edward VII.

“The competitions went with a ‘go’,” said The Northern Echo, “and perhaps the most striking thing to the casual visitor being the many languages in which competitors were urged on to great things. All sorts of weird college and backwoods cries were indulged in by the Americans and the Colonials, who sorted themselves out in groups in the stands to encourage their champions, and a success was heralded by the waving of national flags.”

The afternoon’s eight semi-finals of the 1,500m race were eagerly anticipated, even though the overseas competitors, particularly the Americans, were annoyed at the British organisation. The British insisted that only the winner of each heat could go through to the following day’s final, rather than selecting the day’s eight fastest runners, which the Americans preferred.

This meant Butt’s chances of reaching the final depended on the luck of the draw as to who was picked out to run alongside him in his heat.

And he was drawn in the second heat with the American record-holder, John Halstead. From the outset, the two of them were vying for the lead, the British champ against the Yankee champ.

At the bell, Butterfield was leading, but, out of nowhere, another American, Mel Sheppard, flew past the two of them to win the race in an Olympic record of four minutes and five seconds.

This was a surprise change of tactics by Sheppard, who had lost his three previous 1,500m – in one, he had tried to wrestle his winning opponent to the ground and had been disqualified, and in another he had walked off the track in a huff when getting beaten.

For Halstead, it was a crushing blow, particularly as his US record was four seconds faster than Sheppard’s time, and especially as he’d suffered an upset stomach immediately before the race. But he said nothing, and the Americans applauded his sportsmanship.

Butterfield came third in a creditable 4:11.8 – a time that would have won two of the other heats, and a time that could have been faster if his heart hadn’t sunk as Sheppard whizzed by.

Still, Butt had the 800m heats seven days later to aim for.

This time, he was drawn in the first heat, which was a fast, tight race with Butt swopping the lead with Ödön Bodor, a Hungarian footballer, and Evert Björn, a Swede. By 0.3 of a second – the slenderest of margins – the Hungarian finished ahead of the Darlingtonian.

Again, Butt’s time would have won several other heats, and again the gold medal was won by Sheppard – “Peerless Mel”, they called him as his three golds made him the joint most successful athlete in the games.

For 29-year-old Butt, his race was run – literally. At the end of the games, he retired, and never again appeared on a track.

Instead, he went behind a bar, and became landlord at the Hole in the Wall. The name of the pub had graced Darlington’s Market Place for as long as anyone could remember, but when Butt and his wife and child went in, it was a new building, probably having gone up in 1903.

In 1916, aged 37, Butt joined the Royal Garrison Artillery. He landed in northern France on January 18, 1917, a member of the 230th Siege Battery, which used heavy howitzer guns to rain shells down on the enemy.

He was injured in the summer of 1917, returned to Darlington to recover and then went back to Flanders.

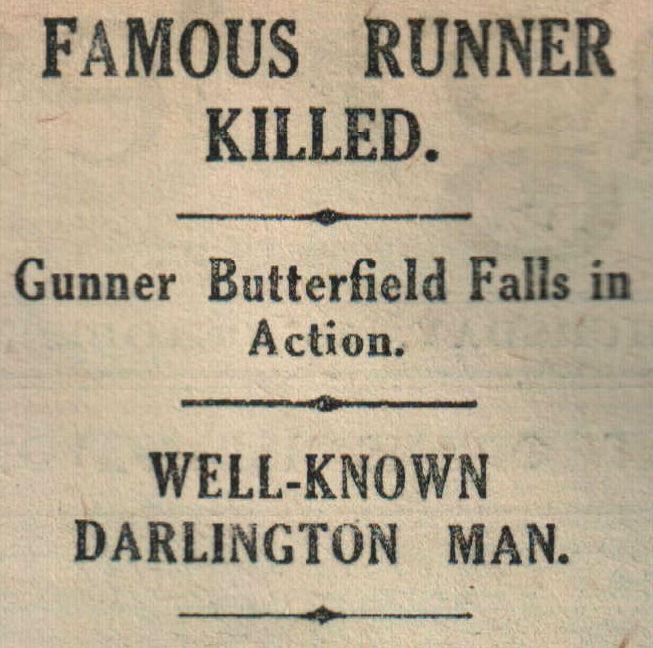

Eight weeks later, on September 24, he was killed – his legs were blown off at Bellewaerde, and now he lies in a Belgian cemetery about three miles from Ypres.

The news of his death filtered through to the Hole in the Wall on October 18.

“Darlington’s place in the annals of sport, for a town of its size, is unquestionably unique, for during the last decade it has produced famous men in all branches,” said a tribute in the Evening Despatch paper. “Perhaps the greatest of them was George Butterfield. He achieved a fame which may be without exaggeration described as worldwide.”

Interestingly, the author of the tribute regards Butterfield’s 1904 race with the great Shrubb – “he actually came within a yard of wresting from him the Ten Miles Championship” – as “the height of the pinnacle to which he climbed”. Today, though, it is as an Olympian that he is best remembered.

The Despatch’s sporting tribute concludes: “When George Butterfield returned to the front a few weeks ago, after recovering from wounds, he had a presentiment that the worst would happen.

“On his departure, he remarked: ‘I have made a name that will stand on the annals of time as a runner, and I will leave my name behind as one who has given his life in honour of his country.’

“His words were true.”

FAMOUS FEAT: How the Evening Despatch told of George's victorious race with a greyhound

IT was a snowy day at the North Yorkshire and South Durham Coursing Club’s meet at Sir Robert Ropner’s estate – we would guess, therefore, that this story takes place at Skutterskelfe Hall, near Stokesley, which was the German-born shipbuilder’s country residence.

Two dogs were to race off, one of which was called Lord Nelson II. The poor hound had a lamentable record and so everyone was backing its spritely opponent.

True to form, when the hare was raised and the race was on, the opponent rushed ahead – but it slipped in the snow, somersaulted and crashed to the ground, dislocating its shoulder.

Off sauntered Lord Nelson, with the fleet of foot hare disappearing into the distance.

One of the spectators was heard to call out in disgust: “I’m darned sure I can run as fast as that. I’ll have a try.”

It was George Butterfield, at the height of his powers, throwing down the gauntlet to a greyhound.

“With that, he scooted off in the tracks of the greyhound showing clearly in the snow,” remembered one who was there. “Away he raced over hedges and ditches hot on the trail, until he was out of sight.”

Out of sight, out of mind, and no one was worried when the worthless Lord Nelson II never came home. “It might ‘ave fallen down deed,” said one. “Just as weel,” said another.

Later that evening, Butterfield turned up in a pub in Hutton Rudby, sweating profusely.

“Following him was the sorriest-looking greyhound imaginable, perfectly abject and weary,” recalled the eye witness. “George said he must have run over five miles over the roughest country he could ever remember, and had captured his quest in a wood.”

Man 1 Greyhound 0.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here