LAST week, Memories was digging bullets out of a grassy bank in Neasham; this week, we are sucking on Black Bullets out of a metal tin from Newcastle.

As well as last week’s investigations into the First World War rifle range on the floodplain at Neasham, we were intrigued by a bungalow in Darlington’s Grange Road which has suddenly shed its rendering to reveal that it was originally built as something else.

But what?

Sheila Ross of Woodham in Aycliffe remembered that her great uncle, Arthur Ernest Richmond, had lived next door to our mystery building in the 1930s and used it as part of his confectionery trade.

“He was one of the four Richmond brothers who left the railways at Shildon and came to Darlington and built a sweet business in Borough Road, opposite the old fire station,” says Sheila.

The Richmond brothers’ sweet factory was established in the late 19th Century and apparently rivalled Peases’ Mill as the town’s main employer of women and girls – if that is true, it must have had hundreds of women boiling sweets. It is also said to have been the first Darlington firm to own a delivery lorry, and one of the first to install a lift and a telephone.

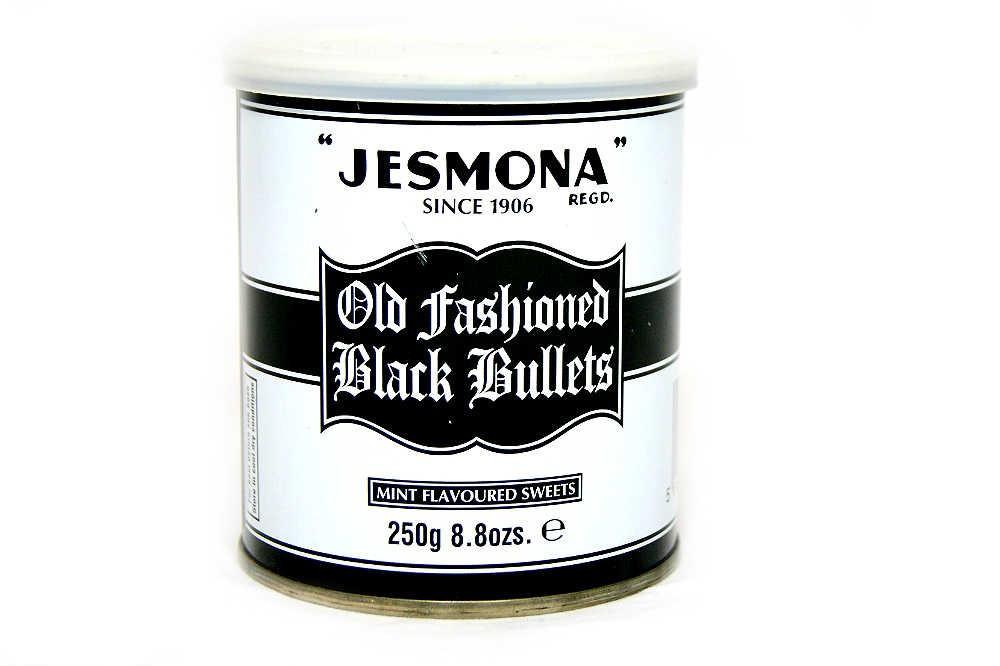

One of its most popular sweets was the “black bullet”, a hard, round, mint.

“Bullet” is a North-East dialect word for a boiled sweet, perhaps derived because these round mints were originally made in the moulds for musket balls. It is said that North-Eastern miners developed a taste for the strong-flavoured, long-lasting bullets to temper their cravings because they were not allowed to smoke underground.

Sheila has an early memory of visiting the Borough Road factory and seeing the workers creating “orange fish” – orange-flavoured, fish-shaped boiled sweets, obviously.

“I saw them kneading great lumps of this orange stuff, like pastry, on long trestle tables,” she recalls.

She also recalls visiting her great-uncle’s home, York House. “My mother took me there at Christmases, and the out-building was used for storage, because they did a lot of delivering around the area, and perhaps as a shop,” she says.

The last of the four Richmond brothers was Edward, and he died in 1950. Around this time, the black bullet business was sold to John H Welch, sweet-maker of Whitley Bay. He, too, was famed for his black bullets – it may even have been him who gave them the name “Jesmona” after the Jesmond area of Newcastle.

And his grand-daughter is Denise Welch, the Loose Woman and former Coronation Street actress. In fact, Denise says that her nickname at school was “Truly Scrumptious” because all the kids knew she came from the black bullet family.

Since the 1960s, the famous black-and-white Jesmona black bullet brand has been owned by Maxons of Sheffield, one of the last traditional boiled sweet manufacturers in the north, and the bullets themselves are available all over the world.

After the Richmonds’ business finished, their sweet factory, which was in the shadow of the Haughton Road power station, became Ferguson Foster’s building warehouse. It was demolished in 1986 and now housing occupies its site.

HOWEVER, this marvellous story does not explain the origins of our long, low mystery building that has shed its render.

It is older than the terrace in which York House stands – it is on the 1898 Ordnance Survey map and the terrace is not.

It stands on the corner of Polam Lane which once led down to Polam Grange, a farm we know little about. Today it faces Sainsburys supermarket, which is built on the site of an early 19th Century mansion called Beechwood. Beechwood, owned by the Backhouse family of bankers, once had “one of the warmest and most pleasant of Darlington gardens, where grapes growing up the house came to perfection in fine summers”, according to historian Vera Chapman.

You still get grapes on the site, but only in the fruit and veg section of the supermarket.

Perhaps, we suggested, our mystery building was a Beechwood out-house – its nakedness without its rendering reveals how it once had a shapely arch facing onto Grange Road, so could it have been a coach-house?

Sylvia Western of Hurworth gently pours scorn on our theory. “As a teenager, a friend and I worked at some boarding kennels at the bottom of Polam Lane,” she says. “They were set up in the stables of Beechwood, two kennels to one stall, so I think the coach-house idea might not be right because it would be too far from the horses.

“The owners of the kennels lived in a cottage in the walled garden also connected to the stables. I remember that the dogs were allowed to go in the walled garden for a bit of exercise.”

This, we have a feeling, may have been Polam Grange, but we could be wrong there, too. Anyone with any other theories?

LAST week, we were stumbling around the floodplain of Neasham in search of evidence of the army camp and rifle range that was there during the First and Second world wars. We carried a picture of a couple of the thousands of bullets which generations of local people have retrieved from the bank that is behind where the butts stood.

Pat Surtees of Darlington responded by sending a picture of a very similar slender bullet that she has with a First World War provenance.

“My husband and I did a Flanders battlefields tour last year to follow up information we had about my grandmother's first husband, John Smith, who died near Ypres in 1917 – we found his name on the Menin gate,” she said.

“Our tour guide found a First World War bullet near the Yorkshire Trench at Boezinge, near Ypres, and gave it to me – it looks very similar to yours.”

In fact, it looks identical.

The Yorkshire Trench was discovered in 1992 on an industrial estate. It had the bodies of 155 First World War soldiers from Britain, France and Germany in it. The trench was dug in 1915, and was fought over on several occasions until late 1917.

It is called the Yorkshire Trench because that it is how it is referred to on a 1917 map.

JOHN BROOKS did his national service at Catterick in 1948, and did his small arms training on the rifle range at Bellerby, near Leyburn.

“We were instructed in the use of a Lee Enfield rifle which was identical to the ones used in the First World War – five rounds in the magazine and one in the breach,” he says.

And the .303 bullets the Lee Enfield fired looked like the two slender bullets in our picture.

Then Tom Robson of Bishop Auckland called. He, too, did small arms training at Bellerby, only in 1947. He agreed with the .303 identification, and then turned his attention to the middle bullet.

“From the picture, it looks snub-nosed and short and heavy, and the calibre looks to be a .45 from a pistol, which had a right old kick when you fired it,” he said.

Like the .303 rifle, the .45 pistol was used in both world wars.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here