DEATH by dirigible came to the Dene Valley a few minutes after midnight on April 6, 1916.

On a starlit night 100 years ago, the captain of a clanking Zeppelin airship mistook the bright lights of Bishop Auckland for Leeds and started dropping bombs on what he presumed was the industrial area.

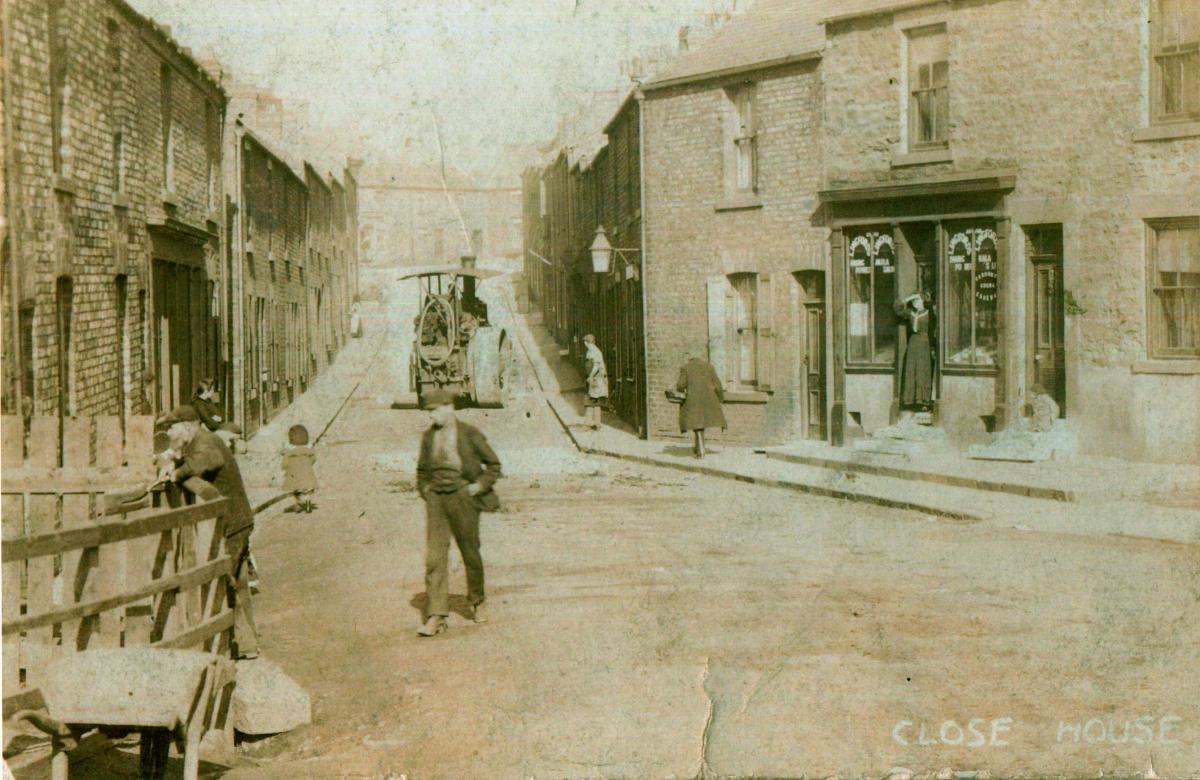

But a couple of thousand feet below him was, in fact, the small mining village of Close House, where, in Halls Row, nine-year-old Robert Moyle was sleeping peacefully until an incendiary bomb smashed a square hole through his roof.

“The bomb dropped right on the bed, and the child was practically cut in two,” said The Northern Echo.

The bomb then exploded, setting fire to the terraced house. Robert’s older brother in another bed in the room managed to escape, but when neighbours eventually got to poor Robert, his body, said the Echo, “was burnt almost to a cinder”.

It was, said the headline, “a devlish piece of German barbarism”.

Amazingly, given the path of terror that the Zeppelin had cut across the sky of south Durham that night, Robert was the only fatality.

The Germans had been peppering the North-East with sporadic airship attacks for a year but April 1916 was the zenith of the Zeppelins’ operations. The giant balloons were based near Hamburg, in northern Germany, and so had only to fly straight across the English Sea to harass the east coast.

April 1 was their most deadly attack, when Zeppelin L11 came ashore at Seaham and bombed Sunderland, killing 22 and injuring 128. It then travelled south down the coast, dropping bombs on muddy flats around Middlesbrough, passing over Saltburn and hurling a bomb at Skinningrove before heading for home.

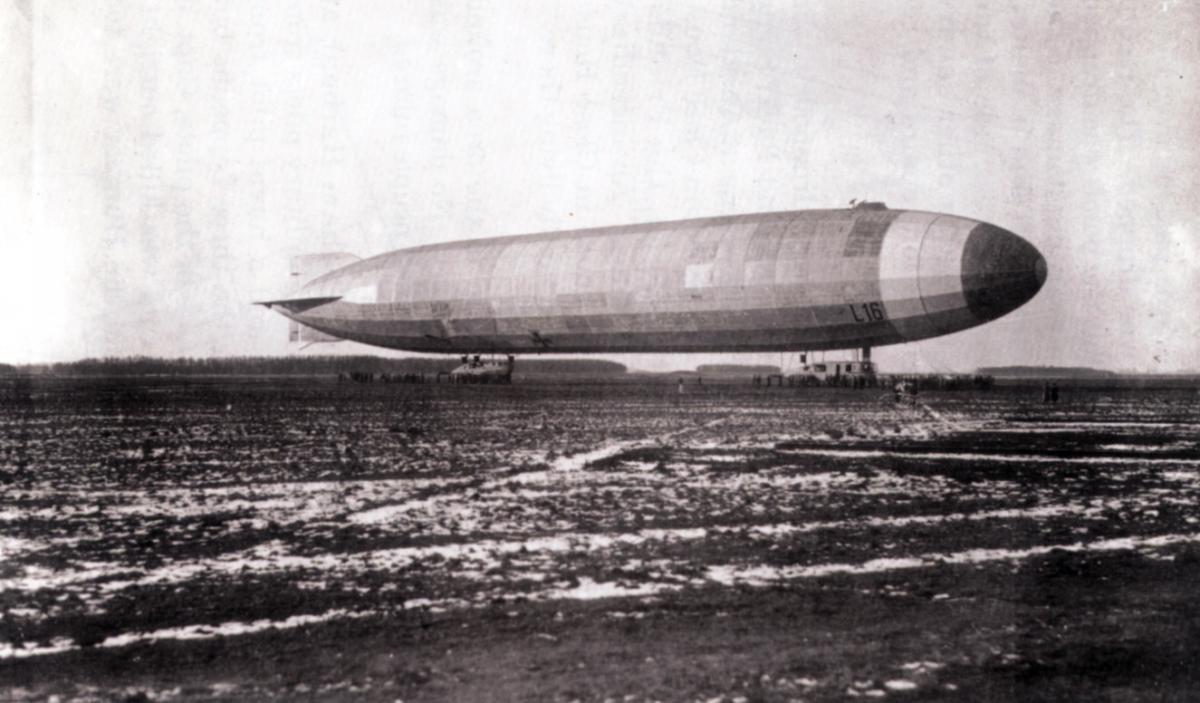

The following night, L16 and L22 marauded over Northumberland, without causing much damage.

But then, at 11.30pm on April 5, L16, captained by Oberleutnant zur See Werner Peterson, arrived at Seaham. It is believed that the captain reckoned he was over Scarborough and so he headed south-west in search of bright lights that he thought would be the telltale locator of Leeds.

But south-west from Seaham took him over rural south Durham. At 11.45pm, travelling rapidly, he passed Sedgefield and skirted south of Bishop Auckland. He could see the blacked-out lights of the town, which he assumed was Leeds, and he could see colliery wasteheaps burning around it. These, he decided, were his targets.

So at 12.03am, over Rainey Fell Colliery to the west of Bishop Auckland, he turned east again to begin his bombing run. He dropped a little to less than 5,000ft so he could see more clearly, and he slowed to about 20mph so he could throw his bombs more accurately.

The burning waste of Randolph Colliery at Evenwood was his first target. He dropped 13 high explosive bombs and ten incendiaries, destroying 15 houses, damaging 70 more, and injuring a man and a child. Beyond these bald facts, no stories from the village of the dirigible drama have survived.

L16 continued eastwards, again skirting Bishop Auckland, before spying the burning waste of the Dene Valley collieries.

There were no air raid sirens to warn the people of south Durham of the imminent danger. In fact, Rainey Fell Colliery didn’t even have a telephone so a policeman had been despatched on his bicycle to pass on the warning – he was still pedalling westwards when L16 passed over his head going eastwards on its bombing run.

The electricity supply to the Dene Valley villages, though, came from Auckland Park Colliery, which dimmed the lights three times to alert those who were still awake.

A far better alert, though, came from the clanking of the 500ft long cigar-shaped dirigible drifting overhead – its engine sounded so ropey that those who heard it believed it must have had a fault.

The Dene Valley villages – Coronation, Bridge Place, Eldon Lane, Coundon Grange, Eldon, Close House, Gurney Valley – run seamlessly into one another, and Peterson flew over the lot, his 18 male crew members lobbing out bombs from the gondola beneath the balloon as they went.

The first fell near Coronation, blowing out the windows in Eldon Lane School and damaging the girls’ playground.

The next landed close to Auckland Park Colliery. In 1909, a German firm had installed a state-of-the-art cokeworks at the colliery and so a rumour rapidly spread that Peterson was using inside knowledge to take out the industrial asset. This, though, credited the haphazard raid with too much sophistication. Auckland Park was a huge complex, employing 1,000 men and boys, and Peterson missed it, many of his bombs landing in fields. Some of the bombs didn’t even explode, and so they were later picked up by local bobbies and stashed under a pile of dung, to minimize the force should they explode, until the military could arrive to defuse them.

L16 lumbered next over the patchwork of terraces that make up Eldon and Close House – so tight that they were called the “narrows”. It was now impossible for the bombs to miss.

From the north side of the Zeppelin’s gondola, the crew appear to have tossed out high explosive bombs, creating panic down below. Mothers in their nightdresses picked up their children and ran, dropping their undergarments as they fled. Next morning, miners on their way to the early shifts found bits of female apparel lying about the place, and, presuming they had fallen from above, started a rumour that the Zeppelin had been staffed by women.

The high explosives damaged properties – Close House shops, the post office, the Friends’ Meeting House, the Co-op.

The crew members stationed on the south side of the gondola lobbed out incendiary bombs which rained down on Halls Row, where the Moyles family were sleeping in No 21.

The father, William, 40, a hewer at Eldon Colliery, was away on active service, so his wife, Hannah, had to cope with the disaster. Robert was killed outright in his burning bed; his little brother, William, seven, sleeping in the next bedroom, had both legs fractured. With the help of neighbours, everyone else escaped unscathed.

L16 continued eastwards, creating more craters in the fields behind the Eldon pit swimming baths, before departing the Dene Valley. In less than ten minutes, it had dropped 17 high explosive bombs and ten incendiaries; it had demolished six houses, seriously damaged 13 more and blown windows out in another 48.

It flew over Sedgefield and crossed the coast at West Hartlepool at 12.45am. Rather heading directly for home, it went north. It was , spotted off Seaham at 1.15am, Sunderland at 1.35am, and Tynemouth at 1.50am. The Royal Flying Corps stationed at Cramlington scrambled to intercept it, but one plane bumped into a hedge and another crashed into a house, killing the pilot, Captain John Nichol, 22, of Margate, Kent.

He and Robert were the only fatalities that night; William the only known casualty.

Robert’s inquest held next day in the village. The jury concluded: “Deceased was killed by an incendiary bomb dropped from enemy aircraft.”

The Echo said: “An expression of sympathy was made by the jury, and the coroner said he had never had to deal with a more devilish piece of barbarism.”

On April 8, Robert was laid to rest in St Mark’s Church, Eldon. “Thousands of people witnessed the funeral of the boy victim of Wednesday’s Zeppelin raid,” said the Echo, its report giving no names or locations in case German spies were reading and feeding the information back to Oberleutnant Peterson.

“The village church was incapable of holding anything like the number of people who desired to show their sympathy with the bereaved family, but they crowded the churchyard to witness the last rites,” said the report.

The unnamed vicar then, in modern parlance, went off on one. From the pulpit, he condemned the Germans’ “barbarous, abominable methods of warfare” which were “absolutely unscrupulous and ruthless, indescribably pitiless and cruel…cowardly and showing a devilish disregard of innocent life”.

The Zeppelin, he said, “was a creature of the night, and appeared only in the darkness like any other evil thing”. It was, he said, “foul, detestable and diabolical” but, he concluded, it would only increase the English people’s resolve to support “the destruction of the hydra-headed monster of German militarism”.

After the night of April 5-6, 1916, British anti-airship tactics improved – Peterson and his crew were killed later that year when they were shot down in flames over East Anglia – so never again did a Zeppelin venture into the Dene Valley, but the coast continued to be harassed by dirigibles right into 1918.

With many thanks to Colin Turner of Eldon for his help and pictures.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here