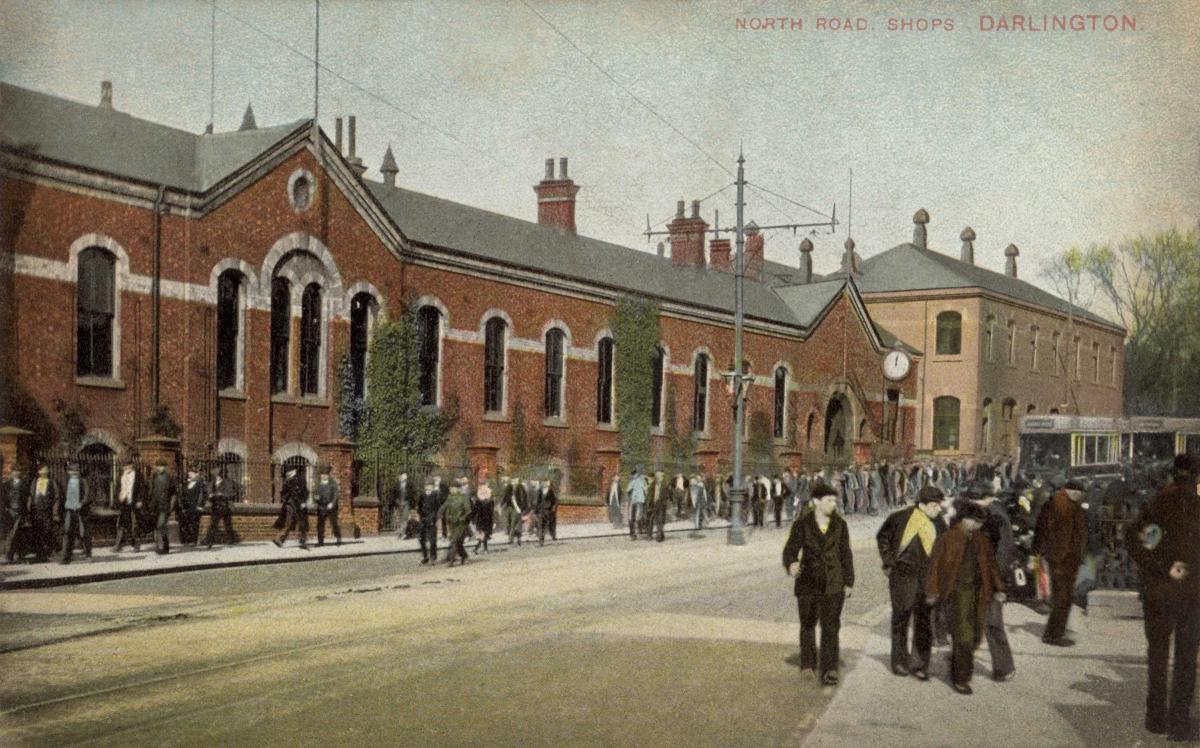

IT is 50 years almost to the day since Darlington’s largest employer closed down, throwing thousands of men out of work. It was a hammerblow to the local economy and put a huge dent in the town’s psyche – Darlington had given birth to the railways in 1825 but the closure of the North Road Shops on April 1, 1966, severed the direct connection.

On the day in 1962 that the closure was announced, The Northern Echo said: “It comes as a shock, as if an apparently unshakeable pillar has suddenly crumbled. Even in the worst years of the Depression, North Road has stayed in business, and a job at North Road was a job for life.”

The history of North Road can be traced right back to the birth of the railways. Although the first engine, Locomotion No 1, was made on Tyneside, Timothy Hackworth soon established his workshop in Shildon as the place where Stockton and Darlington Railway locos were built and maintained.

But the railway quickly evolved away from Shildon. In 1841, the first stretches of the East Coast Mainline opened; in 1851, the discovery of Cleveland ironstone dragged the S&DR towards the coast. It was soon decided that the main workshop needed to be more central than Shildon, and in 1857, farmland on the northern extremity of Darlington was bought for £9,139 9s 4d – where Morrison’s supermarket in North Road is today.

On the six acres of farmland bordering the railway line, William Bouch, the S&DR’s resident engineer, designed the workshops, and they opened without ceremony on January 1, 1863.

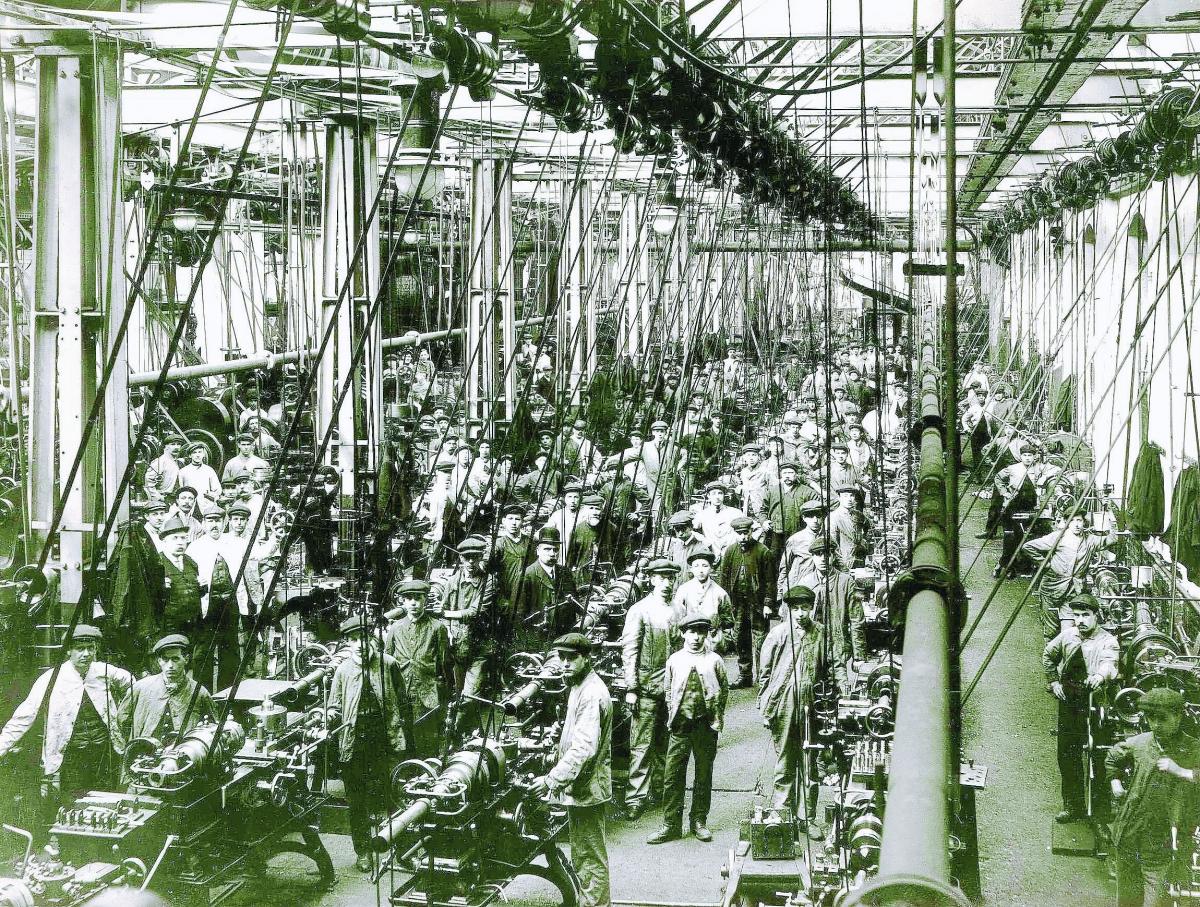

The first employees were 150 men, many of whom lived in the new terraced streets that sprung up alongside the works. They worked for a few pennies an hour from 6am to 6pm Monday to Friday, with half-an-hour for breakfast at 8am and an hour for lunch. They also did 6am to 1pm on Saturday – a 59 hour working week.

By 1872, there were 550 employees, and they earned up to 40 shillings a week – extremely well paid for the time. Plus, the railway company contributed 25 per cent more to the workers’ provident society to cover sickness, accident and funeral costs, and to run the “handsome literary institute” in which there was a library, newsroom, lecture hall, billiard and chess rooms plus a canteen – the institute still stands, as a club, beside the supermarket.

In 1903, the North-Eastern Railway began to close its Gateshead works and move all of its locomotive-building to North Road. The Darlington works spread over 27 acres, and employed 1,500 men whose working week lasted 53 hours and earned them, on average, £1. But if they opted into the works’ drinks round, they were deducted 2d-a-week for their daily pint of tea or 2½d-a-week if they preferred coffee.

They still started work at 6am, but to make sure they were in on time, at 5am a bell was rung in the factory, echoing across the terraces and waking everyone up – especially the wives, who would get up before their menfolk to start a fire.

These were skilled jobs, performing a craft to hone a part that went to the erecting shop to be built into an engine. Every skill had its own workshop: wheel shop, millwrights’ shop, coppersmiths’ shop, brassmoulders’ shop, boiler shop, flanging and tube repairing shop, tinsmiths’ shop, brass finishing shop, plate bending and straightening shop, joiners’ shop, patternmakers’ shop…

There was even an artificial limb shop. Unfortunately, railwaymen across the country were in the habit of losing arms and legs in work accidents. North Road built replacements that railway companies generously gave them for free.

When the First World War broke out, North Road was producing a new engine every fortnight, and employing 2,366 men. During the war, its output tumbled to just a couple of engines a year. Many of its men went off to fight, and 1,000 women were recruited to work in a shell shop, off Wales Street. Only male supervisors were allowed in the shop and the women manufactured 1,500,000 18-pound shells in four years.

After the war, even though the working breakfast was scraped and the shift began at 7.30am, North Road continued to grow. A separate paint and boiler shop had been established at Stooperdale in 1911, and in 1923 a wagonworks was opened at Faverdale producing 10,000 timber wagons and carriages a year. Darlington was now a complete railway town with many thousand well-paid railway jobs insulating it against the worst of the Great Depression that blighted the rest of the country.

Even so, there were four-day working weeks and long, unpaid holidays over Christmas. These, though, may have given the railwaymen time to prepare their bi-annual carnivals which became the highlight of Darlington’s calendar, and which raised £30,000 in the inter-war years to build the Memorial Hospital.

In 1929, in secret behind a large curtain to prevent spying, North Road men built locomotive No 10,000 – the “Hush-Hush”, which was Sir Nigel Gresley’s first revolutionary experiment in streamlining.

The Second World War was kinder to North Road than the first, but in peace-time it entered a new age: on January 1, 1948, the big four private companies were nationalised to form British Railways. Initially for North Road, this was positive: in 1954, it employed 4,000 men – its biggest register – and they built 50 locomotives a year while maintaining the national fleet of 1,724 engines.

A negative, though, was on the horizon: the creeping dieselisation of the BR network. For a workshop designed to build steam engines, this was bad news. North Road did try to convert to the new technology and in 1956 it was at full capacity, making ten steam locos and 45 diesel engines, and repairing 684 locos.

After 94 years, the steam era came to an end when the last of North Road’s 2,269 steam locos, BR No 84029, rolled off the production line in October 1957.

Darlington was now wholly devoted to diesels – but more troubles were ahead. In 1960, with passengers and goods opting to travel by the new motorway system, BR lost £42m. On March 15, 1961, the Conservative Transport Minister Ernest Marples announced that he was appointing Richard Beeching, the chairman of ICI, to take charge of BR and return it to profitability.

One of Beeching's first announcements came on September 19, 1962: 18,000 jobs in railway workshops across the country were to go, including 3,000 in Darlington.

Next week, we’ll look at the SOS campaign “to save our shops” and how the hammerblow of closure fell on April 1, 1966.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here