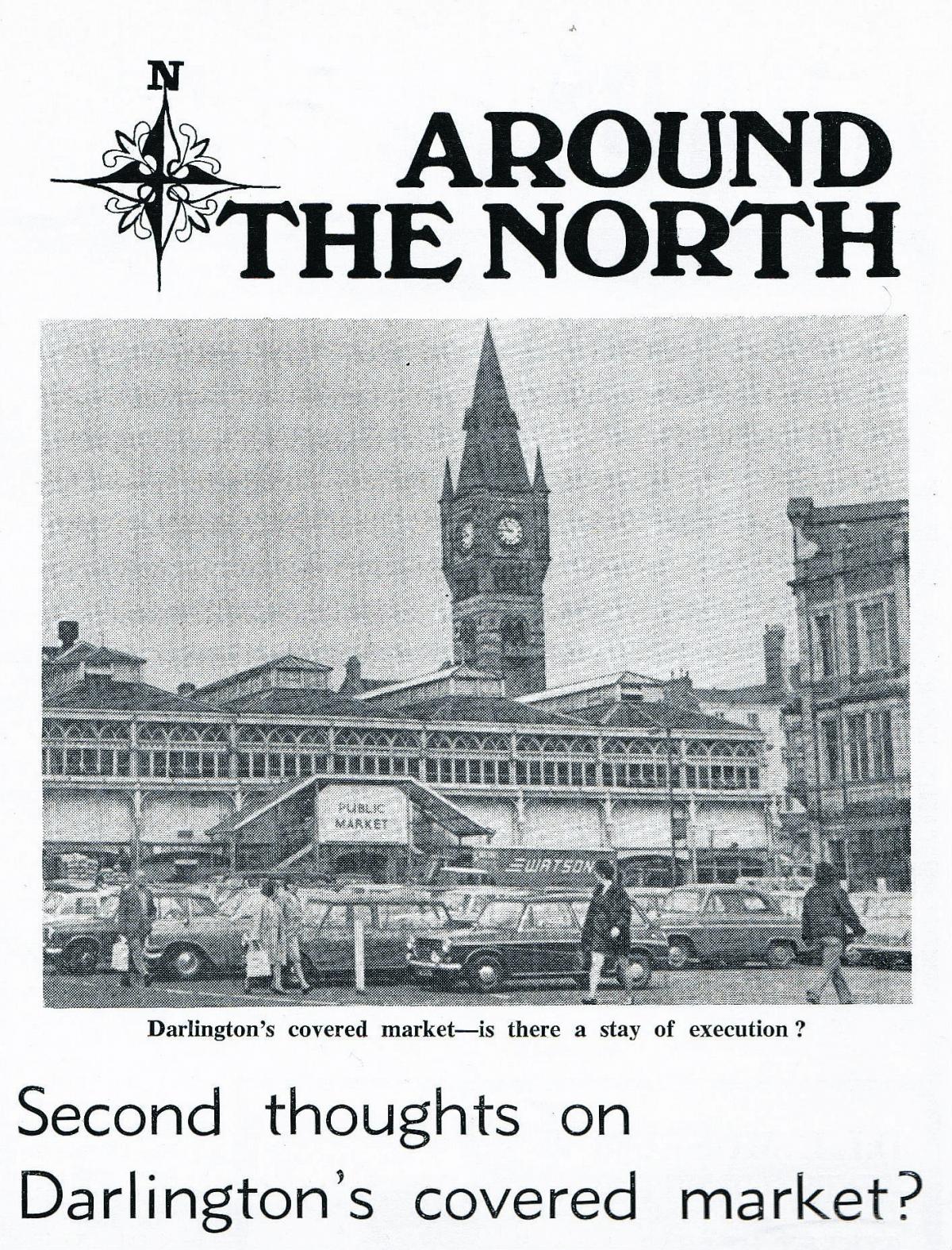

“DARLINGTON’S COVERED MARKET is a most successful place: it’s always bustling with shoppers and the stalls are varied and full of exciting buys,” said the North Magazine in its November 1972 issue.

“There are vegetable stalls where you can buy fresh mangoes and green marjoram, there’s a delicatessen where you can get a hunk of parmesan as long as there’s someone strong enough to cut you a slice; there’s a newsagent’s where foreign magazines like Paris Match and Elle are on sale, and there are plenty of stalls with fresh eggs, tempting vegetables and new bread.

“It always seemed a shame that all this was to go.”

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, all of Darlington town centre was under threat from council-sponsored developers. The Shepherd Scheme and then the Tornbohm Plan intended to demolish the covered market complex, Bakehouse Hill and Houndgate and cover the whole area – including the open market – with hideous, characterless concrete and glass boxes, in which there would be square shops, square offices, a square theatre, a square municipal centre and a square multi-storey car park.

“Would the new centre be such a success or would it tend to suffer from that typical problem of new centres – too high rates which drive out all but the richest shops and chain stores?” asked the magazine.

But the townspeople fought back, and managed to win public inquiries and also gained preservation orders from the Department of the Environment for Bennet House, at the top of Bull Wynd, and the covered market plus its iconic clocktower.

The North Magazine – 20p a monthly issue – was reacting to the news of their victories.

“Personally, we feel rather bucked,” it said. “We never did really understand the need for a new town centre when most people were perfectly happy with the old one. It seemed that a bit of a fad was going round the country – and authorities could not feel dignified enough unless some grandiose plan was on the drawing board for their town.”

Forty years later, there is another grandiose plan on the drawing board for the covered market. This time it is so grandiose that the library has been sucked into it as well.

But last weekend, the townspeople once again showed that they were prepared to fight back, with hundreds turning out to oppose the cuts.

Four decades ago, the campaign did preserve the town centre – and Darlington’s identity and character. Let’s hope the 2016 campaign is similarly successful and then we can all say how “bucked” we feel.

THE North magazine has been sent in by Dr Fred Robinson, professorial fellow at St Chad’s College at Durham University. “I picked up copies of in the hospice charity shop in Durham the other day, and have thoroughly enjoyed the trip down memory lane,” he says.

One of the articles in it is about a cull of grey seals on the Farne Islands – apparently the best way to preserve the over-crowded colony was to send in Norwegian hunters to kill half of the breeding population. In the article, science writer Judith Hann – a Durham University graduate – suggested otherwise, and within two years was presenting Tomorrow’s World on television.

Another article caught our attention. It was headlined “Taverns of the Turf”, and it was about pubs named after racecourses and racehorses.

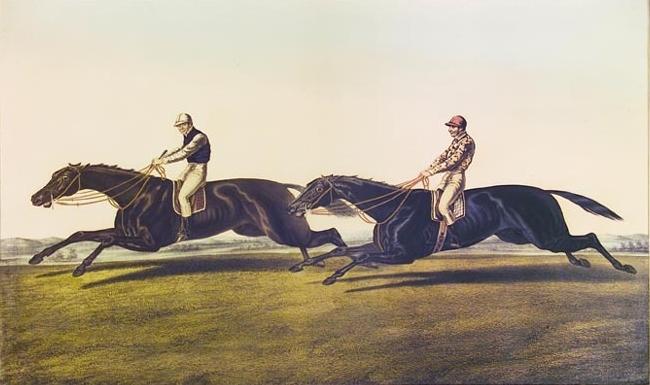

In Thornaby, it said, there was a pub called the Flying Dutchman. It was named after a Middleham-trained colt which, in 1849, won the Derby and the St Leger. The following year, Voltigeur, bred in Hartlepool and owned by Lord Zetland of Aske Hall, near Richmond, won the two prestigious titles – the St Leger, after a dead heat forced it into a re-race.

Two days later, came the Doncaster Cup: a showdown between the unbeaten Flying Dutchman and Voltigeur. Perhaps because the Dutchman’s jockey appeared the worse for drink, Voltigeur won, but such was the appetite to see these two great Yorkshire horses that a rematch was arranged for the following spring.

It was held on May 31, 1851, for a prize of 2,000 guineas at York’s Knavesmire – before a crowd of anything up to 150,000. People walked from Richmond just to be there.

This time, a more soberly ridden Dutchman flew to a famous victory.

However, in the battle of the pubs, Voltigeur has won. The Thornaby hostelry closed a couple of decades ago, whereas Spennymoor’s Voltigeur still serves.

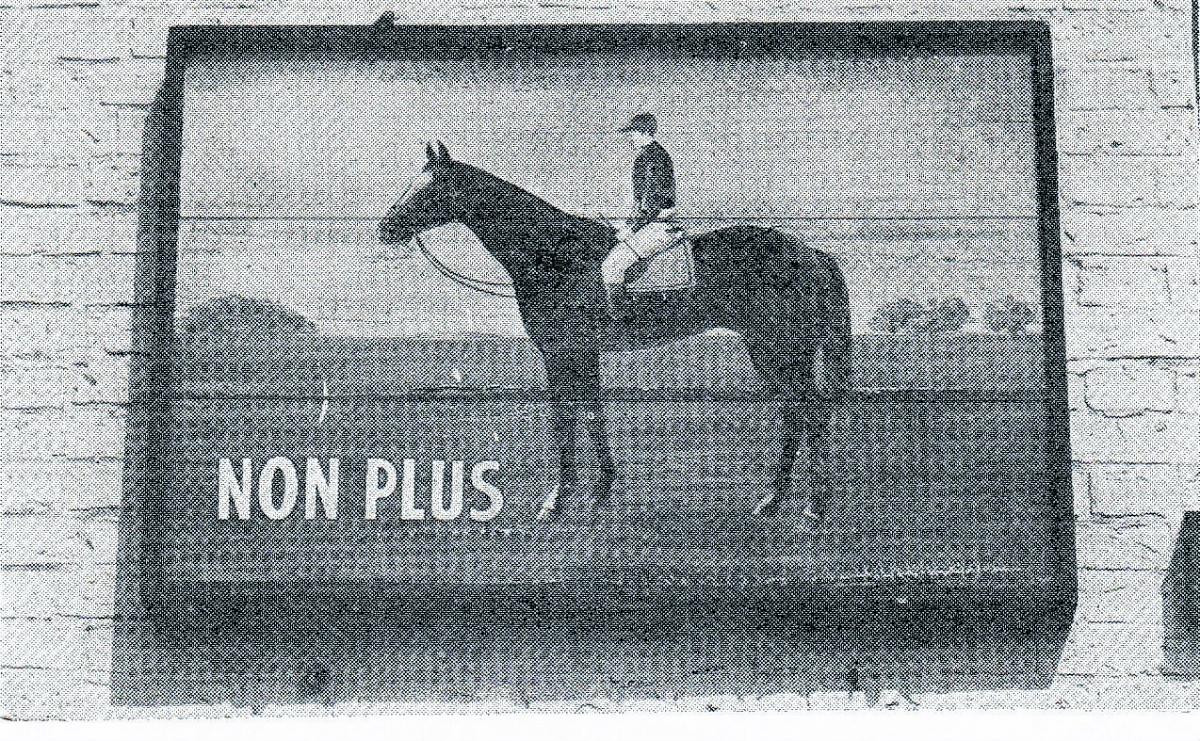

In Morton-on-Swale, said the North Magazine, there was a pub called Non Plus which kept alive the name of the 1827 winner of the St Leger at York. In fact, Non Plus, which was bought by the Duke of Cleveland, of Raby Castle, for 3,000 guineas, also won races at Catterick Bridge, Richmond and Northallerton racecourses.

The Non Plus at Morton-on-Swale, which is just a furlong or two from the Catterick finishing post, was renamed the Swaledale Arms in the late 1970s and was demolished for housing only a couple of years ago.

All of which got us thinking: what other pubs are there/have there been in our area named after racehorses.

IN May, Barnard Castle School is holding a reunion for Old Boys from the 1940s and 1950s on May 11 from 11am. It will be a day for reminiscing, as old photos will be on display – like the one above which shows the 1953 1st XV – and there will be an opportunity for a tour of the school to see how things have changed. After lunch, there will be a cricket match between the school 1st XI and the MCC. Please contact Dot Jones on 01833 696025 or e-mail dj@barneyschool.org.uk for more information.

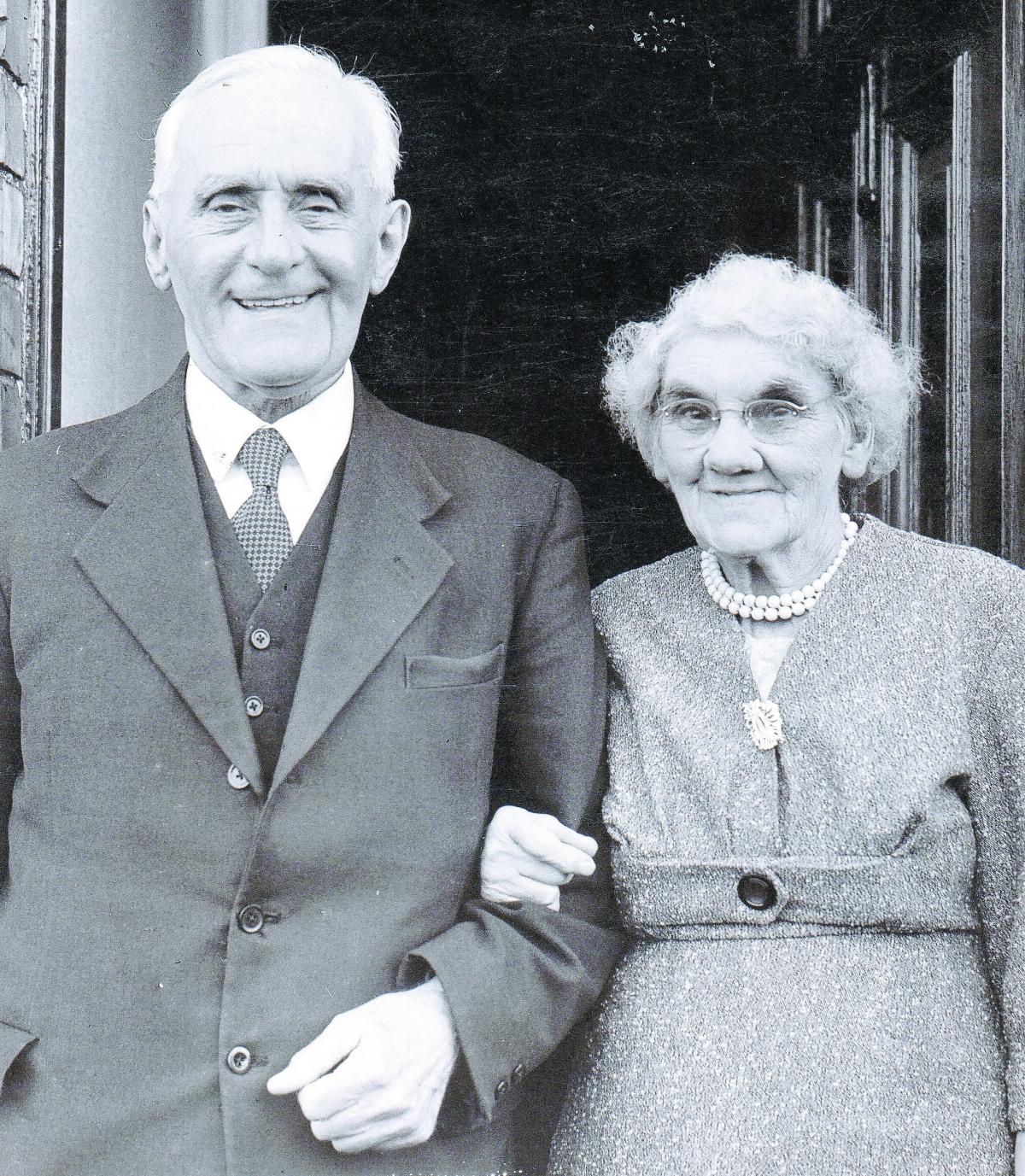

LORD LAWSON of Beamish was a truly remarkable chap: born in 1881, he came from an illiterate Cumbrian fishing family, started down Boldon Colliery the day after his 12th birthday, but rose to represent Chester-le-Street for 30 years in the House of Commons, becoming Secretary of State for War in his friend Clement Attlee’s Cabinet in 1945, before becoming Britain’s first pitman peer in 1949.

He was also, as Memories 238 told, the uncle of George Reynolds, the former chairman of Darlington Football Club.

Now Lord Lawson’s story has been told by Dorothy Rand in a book which draws heavily on his own writings – his autobiography A Man’s Life was best-seller in the 1930s, and Dorothy has also used his unpublished papers which are held by Durham University Library.

His words come from a different age, both in tone and content. He writes of his first day down the pit – “the eerie hours I spent in the dark” – and of his amazement at seeing “a Thing running in the streets of Sunderland without any horses pulling it” – the first motor car.

In his youth, he “gambled like the devil and read like a leech” and through the power of his intellect, and with the undying support of his wife, Bella, made it to Oxford University. His time in Parliament is fascinating, but the most powerful passage is from May 1, 1942, when their home in Beamish was badly damaged by German bombs.

Nearly 24 hours later, the community was being to rejoice in how it had escaped the raid without fatalities, when a bomb with a time delay fuse, hidden in a cellar, exploded.

“I scrambled over great boulders of stone in a thick cloud of dust,” wrote Jack. “Over the road a good neighbour lay badly broken. First Aid men emerged and tended to him.

“’Mr Lawson.’ I turned. Another neighbour stood silently looking at another body.

“Again he called my name and just looked at me.

“’Is that Clive?’

“’Yes’.

“I went to him. The body was warm but…my boy was dead.”

Clive, his adopted son, was only nine.

“His Ma’am! I turned down the street to tell her. We met halfway.

“’Have you seen Clive?’

“She looked at me and said: ‘Howay, you and I have work to do here.’

“’Yes’. She straightened up, turned away and went to those in need.”

Knowing that nothing could be done for their darling lad, Bella went in search of the living who could be helped.

“I returned to bring in my boy,” continued Jack. “A young miner begged me to let him carry the body. I remember saying that I had carried him often and could certainly do it now. Gently and firmly he insisted. He knew the boy was badly broken and wished to spare me the ordeal. I shall never cease to be grateful to Fred Watson for that kindly action – miners are like that.”

He was made a lord just after he had retired as an MP and, the following year, became the first peer of the realm to march in front of a miners’ banner into Durham for the Big Meeting. To him it was entirely natural, as he didn’t miss a gala for more than 60 years until his death in 1965, and because he felt absolutely at home among his working class people.

Shortly before he died, he wrote of his and Bella’s humble lifestyle: “We have no regrets. My wife and I have done what we ought to do and found deep satisfaction doing it. All the money in the world could not buy that satisfaction. We have revelled in doing our duty, as we saw it, and found joy unspeakable. We live now in the same kind of house as when we started life together; in the same kind of street; among the same kind of people. And there we will end our days.”

A Durham Miner And His Wife – Jack and Bella Lawson by Dorothy A Rand is available for £13.95 (including postage) from Dorothy at 11, Industrial Street, Pelton, Chester le Street, DH2 1NR. Phone 0191-370-0433 or email dorothyrand288@btinternet.com.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here