MEMORIES 266 branched off into politically incorrect territory when it told the story of the Black Boy branchline – a 2.5 mile railway which ran through the centre of Shildon and down to the narrow, exposed coal seams of the Dene Valley.

Since time immemorial, small boys had been sent into those small seams to dig out the black gold. The boys would emerge from the seams covered in dust, and so the mine in the Eldon area was known as “the Black Boy”.

The Black Boy branchline ran from beside the coal drops in Shildon’s Locomotion museum up the bank into what became the town centre. It ran along Cheapside to the very top of the bank from where the wagons rolled down to the Black Boy pit.

When the branchline was opened in 1827, it was horses that did the hard work, hauling the wagons to the top of the bank and then getting a ride down in a dandy cart.

Soon afterwards, new steam technology was applied in the form of stationary engines: these were fixed at the top of the bank and pulled the wagons up using a thick rope.

When the Stockton and Darlington Railway (S&DR) opened in 1825, it had two stationary engines – at Etherley and Brusselton – to help its coal trains get up the hills.

Black Boy was the third, and its engine was placed near the engineman’s house of Rose Cottage at the top of the bank.

The S&DR had two other enginemen’s houses on the incline: one lower down in Shildon in what is now Fulton Court, and the other at the bottom of the other side, in Eldon at Black Boy Bankfoot.

Jane Hackworth Young, the great-grand-daughter of Timothy Hackworth, has researched the history of these early inclines. Her work shows that George Stephenson and Hackworth brought skilled men from the collieries of Tyneside to work on their S&DR, and they placed Thomas Greener – a ship’s carpenter from Killingworth – in charge of the engine at Etherley.

He moved on to work the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in 1826, and left his brother John to look after Etherley. John, poor chap, fell under the beam of the engine in 1843, and was killed.

The first engineman at Black Boy was another Greener, Nicholas, who must surely have been related. He lived with his wife, Jane Maddison, of Toft Hill, in the principal engineman’s house in what was then Fulton Terrace.

In the late 1850s, the S&DR placed plaques on its residential properties. Each line was given a letter – the line from Darlington to Aycliffe to Shildon was allocated the letter “G” – and each property was numbered, so there were unique identifiers affixed to each house. Nicholas Greener lived in G11. The engine house at Rose Cottage was G12 and Black Boy bankfoot was G13.

The G11 plaque, and its house, has completely disappeared; G12 is still in its rightful place on Rose Cottage, and G13 has been removed although its bankfoot railway house still stands.

THE “G” line was effectively the original S&DR, and the first property on it to be given a plaque – G1 – was the Whiley Hill coal depot and crossing house.

Whiley Hill is a curious corner of the railway network. Take the A167 north out of Darlington and, before the A1(M), you climb to a dangerous hilltop crossroads on which the Foresters Arms sits. Turn left here down an intriguing lane: on one side is an old manor house, on the other is the site of the lost medieval village of Coatham Mundeville; further on is a curiously remote former chapel. You go over the motorway and eventually, just before the lane peters out into a farm track, you come to an isolated level crossing. Here is the crossing keeper’s house still bearing its plaque – we’d love to know more about the history of this intriguing lane.

After G1, the next plaque on the line was G2 which was on the Heighington station house, next to the famous Locomotion No 1 pub. Both plaque and house have disappeared.

Then the line ran on round Aycliffe and into Shildon. There must have been more properties marked with G plaques, but no one knows where until the trail resurfaces with the enginemen’s houses at the top of the Black Boy branchline.

THE houses, shops and pubs on the east side of Cheapside, in Shildon, faced the Black Boy branchline which ran up the west side of the street.

On the right, there still is the King William pub, which we guessed was named in honour of William IV who succeeded to the throne in 1830, just as the bank top area of Shildon was expanding rapidly.

In our pictures in Memories 266, another sign could clearly be seen on the side of a shop: “John Boddy, grocer and provision dealer.”

Tina Pole in Darlington, with the help of her husband, Fred, is researching her family tree, in which shopkeeper Boddy features. His father was Christopher, who was born in Middridge in 1830. The Emmersons of Shildon were also tied in to Tina’s family, and, during the First World War, one of their members was a councillor, but as he was a conscientious objector, he was booted off.

Richard Barber in Darlington also spotted a familial link to Boddy’s provision dealership. “It belonged to my great-grandfather’s brother, John Boddy, which I think makes him my great-uncle,” he says.

The Boddys were obviously an entrepreneurial family, as a couple of hundred yards away in Church Street, Watson Boddy – Richard’s great-grandfather – had a general emporium. It looks to have been a splendid shop, full of cans with even a tin bath hanging over the door.

The out-buildings behind the emporium used to have a sign on them saying they were “Boddy’s Buildings”, but this seems to have disappeared when a funeral director took them over, for obvious reasons.

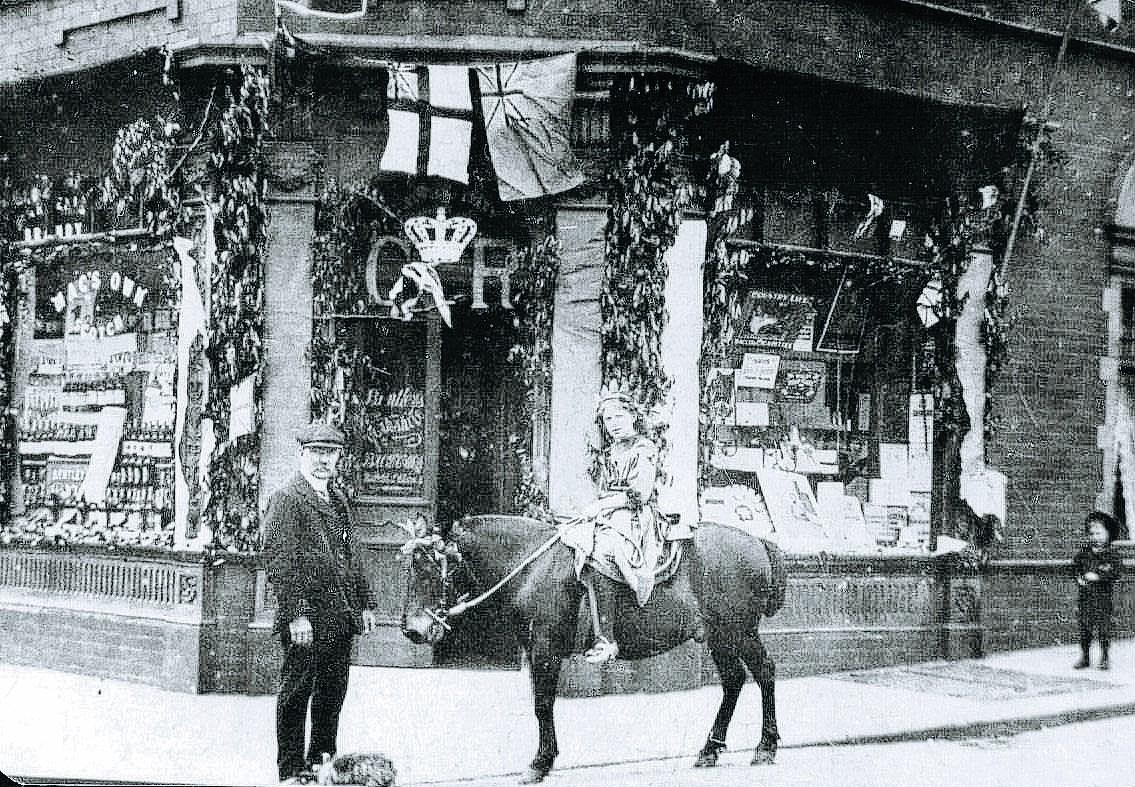

Another photo in the Boddy archive shows little Eve Boddy riding a pony outside a wine and spirit merchants on the corner of Church Street and Association Street.

This curious building, with its ornate terracotta work around its doors and windows, really catches the eye. It may once have gone by the name of Ben Lomond House, which must refer to the Scottish “Munro” mountain. In Ben Lomond House, Ben Lomond lemonade was once made – if you know any more about the Ben Lomond connection, we’d love to hear from you.

Richard says: “I believe the First World War brought about the end of the Boddy empire, and by the 1960s, the family only had four houses that were rented out. Then Shildon council bought them from us for a new road development which has yet to be started!”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here