DANBY WISKE is an agricultural village about four miles north-west of Northallerton. Its name suggests that Danish invaders once settled there, and, in more recent times, East Coast Main Line passengers also alighted there.

The station at Danby Wiske was fairly busy – at its peak, at least ten trains a day called in, and there was a siding for farming goods trains to rest in.

Plus, on the track, there were unusual troughs where water-guzzling steam locomotives filled up in the most spectacular fashion.

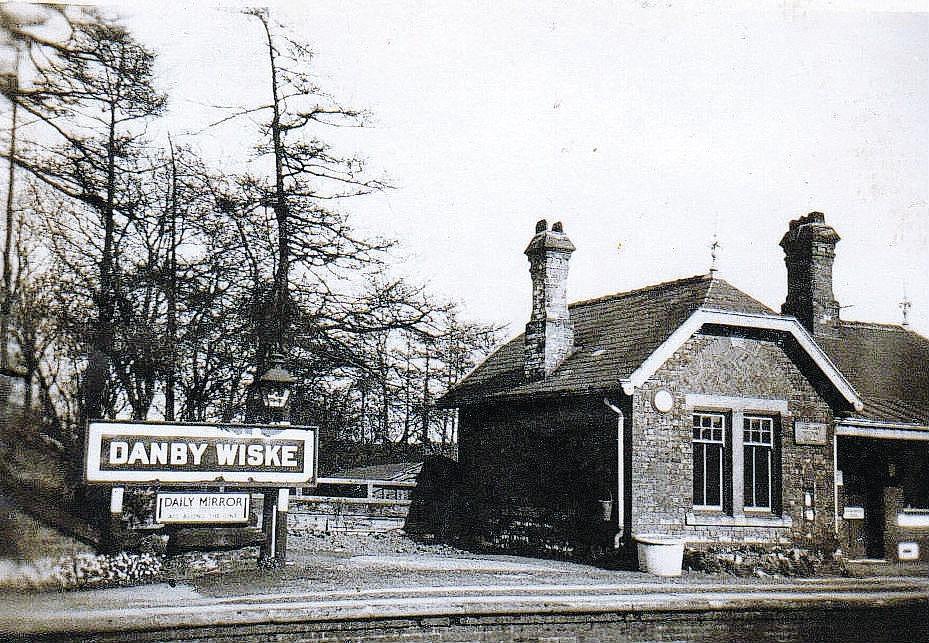

Just before Christmas, searching for information, Memories published a picture of the station which was demolished soon after it closed in 1958. Today there’s just a bare patch on the east side of the mainline where it stood, although the stationmaster’s house still stands on the west side.

Responses to our request were many and various.

First of all, Roger Jennings sent in some details of the station.

The mainline opened in 1841, but it wasn’t until June 5, 1884, that the North Eastern Railway decided to build a station at Danby Wiske. Railway architect William Bell, who was building Darlington’s Bank Top station, knocked out a “half-hipped roof” design that he went on to use on several other small stations.

The station cost £361 6s 4d, and opened on December 1, 1884 – the Darlington & Stockton Times giving it a paragraph.

Says Roger: “The delay in opening is interesting, because between 1841 and 1884, the population of the village dropped from 546 to around 290.”

In 1887, five northbound and five southbound trains stopped there every day, plus two in each direction on Sundays.

The movement of farming goods was obviously an important part of the business case for Danby Wiske station, and Geoff Solomon in the village reports that there was talk of a major railway yard being developed off the siding.

But around the time the station was opened, a long, shallow water trough was added between the tracks on the line nearby.

Non-stop steam engines travelling from London to Edinburgh and Aberdeen needed to fill their tanks with a couple of thousand gallons of water every 50 to 100 miles.

Shallow troughs hundreds of yards long were placed between the rails and fed with water from a lineside tank.

As the engine, travelling from 45mph to a dangerous 70mph, approached, the driver lowered a scoop into the trough, and the train’s forward motion sent the water rushing up into the tank.

It was an extremely wet operation, with water spraying all over the place. Windows in the carriages had to be shut otherwise passengers would get an unexpected shower.

It was also quite a labour intensive operation. The lineside tank was filled from a natural source, but the water had chemicals added to it to keep it clean and to stop it frothing, and to prevent the tank from rusting. In winter, a lengthsman had to keep a fire burning to prevent the water from freezing; in autumn, he was employed keeping fallen leaves from clogging up the troughs; in a dry summer, he had to make sure there was always water for the engines to pick up.

And then he had to tend the oil lamps, which marked the start and end of the trough and informed the men on the footplate when to lower and raise the scoop.

Locations for the troughs were carefully selected. They had to be on a long, straight stretch of line in a slight natural dip. Because trains were travelling fast, they couldn’t be near mainline stations like Darlington and Northallerton, and because of the water spray, they had to be in remote locations.

There were six troughs on the East Coast Main Line in England. Heading north from King’s Cross, they were at:

Langley, south of Stevenage

Werrington, north of Peterborough

Muskham, north of Newark

Scrooby, south of Doncaster

Wiske Moor, south of Danby Wiske

Lucker, between Newcastle and Berwick.

So was Danby Wiske station built partly to service the water troughs?

IN the early 1990s, while working for British Railways, Andrew Bowers spotted some interesting-looking maps languishing in a skip, and so sensibly liberated them.

One of them is dated 1902 – revised in 1905 – and shows the lay-out of Danby Wiske station. The maps appear to have been drawn after the road bridge was built next to the station to replace level crossing.

The map shows how the station must have been a hive of activity. There’s a platelayer’s cabin by the bridge, and a signal cabin controlling access to the loading dock and the warehouse. The stationmaster’s got a greenhouse next the waiting shed at the bottom of his garden, and near the station, there was a cesspool!

WINIFRED MANSON, 90, of Darlington, writes to say: “Oh, indeed I have happy memories of school holidays I spent with grandparents at that lovely station.”

Mrs Manson stayed with her grandfather, who was a railway ganger living in the Danby Wiske station houses, and she watched the comings and goings: farmers and animals off to market, Marshalls the butchers taking delivery of carcases, milk churns being loaded and unloaded, children off to school and college…

“It was then safe to put a child on the train, always telling the guard they were on and which station they were getting off,” she says.

Mrs E Smith, of Northallerton, whose picture of the station started all this off, recalls her mother getting the 8.30am train from Danby every Saturday to do her shopping in the Co-op in Priestgate, Darlington.

And then Ken Donald, of Northallerton, phones to say that he grew up at Hutton Bonville, a mile up the line from Danby. At the age of 13 in 1948, he passed a scholarship exam to go to Eston Technical College at South Bank to study farming.

He’d cycle to the station on a Monday morning, change at Northallerton and Eaglescliffe for South Bank, lodge in Eston for the week and come back home on Friday evening to find his bike still waiting for him.

What a different world!

THERE is more to Danby Wiske than just its lost station, as 10,000 walkers a year know. It is on Alfred Wainwright’s Coast to Coast walk, although Mr Wainwright was not especially enamoured by the place. “Less attractive than its name,” he wrote in 1972 when he was devising the walk. “At 110ft above the sea, it is the lowest point between the coastal extremities of the walk…”

But it certainly has its attractive points.

There’s a lost medieval village at Lazenby, and the Danby vicarage sits enclosed within an old moat.

The church probably once was dedicated to a saint, but the records were destroyed during a Scots raid in the 12th Century, and people forgot.

Above the church door is the only Norman tympanum – a stone carving – still in its original place in North Yorkshire. It was created between 1090 and 1120, and shows three figures engaged in an activity. Is one of them the Angel of Judgement weighing a human soul with the Angel of Mercy tipping the balance in favour of the deceased, or is it a depiction of the parable of “the wise and foolish virgins”? One thousand years ago, everyone would have known the story, but now we can only guess.

And then, sleeping in stone by the altar, is a life-size effigy of Matilda, the second wife of Brian Fitz Alan of Bedale. Matilda may have been the daughter of the king of Scotland and she is believed to have died around 1340.

BUT Geoff Solomon, in Danby, offers the greatest fascination of all. Look at our map. Find Northallerton and head north. See how an old road bears left to Danby Wiske before turning a right angle to rediscover its route to the north.

Then see how the A167 forks off the old road and heads superfast towards Darlington without any kinks.

The story goes this straight stretch of A167 is a by-pass, built by French PoWs captured during the Napoleonic Wars and put to work straightening the Great North Road to speed up the passage of military supplies.

The French prisoners also did remedial work a little further north at Lovesome Hill, diverting the A167 away from the hamlet and digging out a cutting to make the journey easy and flat.

Geoff's 1698 map of the Great North Road names the hamlet "Lowsey Hill" – which could have been pronounced “lousy”. “Some estate agent will have decided that Lowsey Hill did not sell houses,” says Geoff, and so the name was changed to the more romantic-sounding Lovesome Hill.

Memories has long been fascinated by this stretch of road, lined with metal mileposts and running through the fields where 12,000 Scots soldiers died on August 22, 1138, during the Battle of the Standard.

Can these theories of French PoWs be correct, and can you tell us any more stories of Danby Wiske, Lovesome Hill and, especially, Hutton Bonville and its isolated church beside the East Coast Mainline?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here