THE centenary of the Durham Miners' New Hall has been described by the current general secretary of the Durham Miners’ Association as an opportunity to “remember our defeats and celebrate our triumphs”. Over the last 100 years , Redhills, as the hall is universally known, has seen plenty of both.

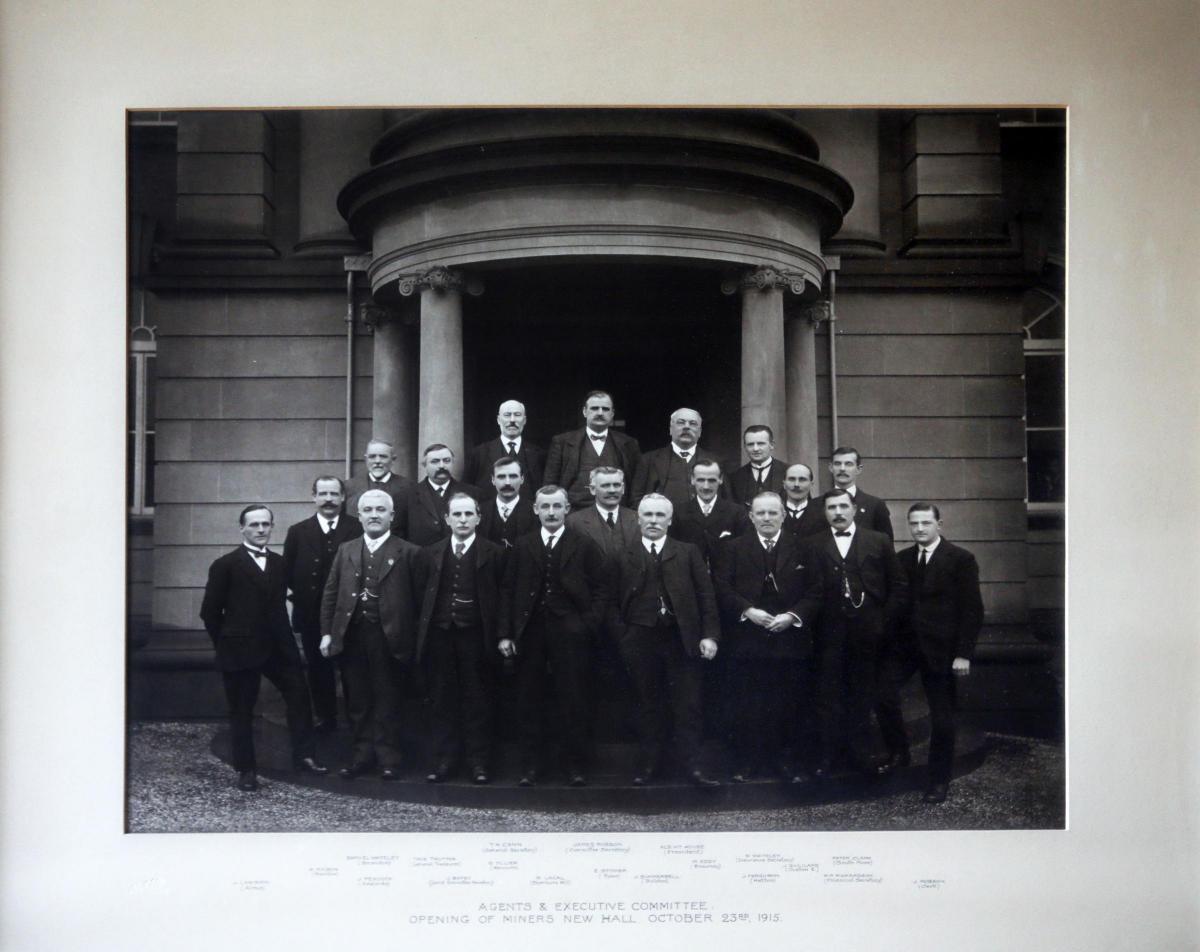

It was opened on October 23, 1915, by Thomas H Cann, the newly elected general secretary of the Durham Miners' Association (DMA).

In his speech, James Robson, the executive committee secretary, regretted that the gathering had been overshadowed by the outbreak of war in Europe, and publicly remembered the thousands of miners who would have attended, had they not been fighting in foreign fields.

It was an “epoch-making day” in DMA history, said the Durham Chronicle, and printed a description of the “palatial buildings” with such depth and precision that it puts today’s journalists to shame.

Coal production, though, had peaked three years earlier, and one might argue that the century that has followed has been largely a story of decline.

But the union leaders gathered that day were not to know that. DMA membership stood at a staggering 120,000, spread across 20 lodges. Coal truly was king.

Indeed, it was the sheer size of the coalfield workforce – and DMA membership – that had triggered the construction of Redhills. The Durham Miners’ Mutual Association, as it was first called, already had 40-plus years of history behind it by 1915, having been formed by miners’ delegates meeting at the Market Hotel, now the Market Tavern, in Durham Market Place on November 20, 1869. It was not the first miners’ collective, but it was the first that would endure. At a meeting of December 18 of the same year, 19 delegates gathered representing 1,964 coal workers.

Two years later, on August 12, 1871, the first Durham Miners’ Gala was held, attracting 5,000 miners and their families to the city’s Wharton Park; and the following year the Gala switched to its present venue, Durham Racecourse. Records suggest up to 70,000 marched along Elvet, “much to the discomfort of the genteel residents of Durham City”. Some things never change.

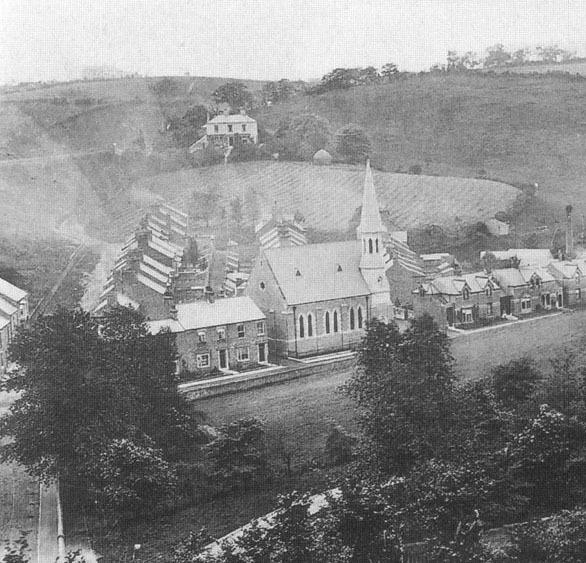

By 1876, membership had reached 50,000 and John Forman, who served as miners’ agent from 1872 to 1900, opened the first purpose-build headquarters, which still stands on North Road. With a capacity of 300 and costing £6,000, “this fine Gothic building…was a firm statement that the union had arrived,” according to the present DMA general secretary, Dave Hopper.

But within four decades, it was too small and the miners started looking for a new home. The Redhills site, the name of which has been romantically credited to the rise being red with the blood of Scotsmen killed at the Battle of Neville’s Cross but is probably, less interestingly, taken from “reedy hills”, was owned by the nuns of St Thomas’ Convent, who lived in the neighbouring White Villa.

They had hoped to build a school and college and, in 1906, got as far as asking Durham-based architect Henry Thomas Gradon to create a design. But the money could not be found and so a few years later the DMA stepped in – turning once again to Gradon, who by then possessed a detailed knowledge of the hilly plot.

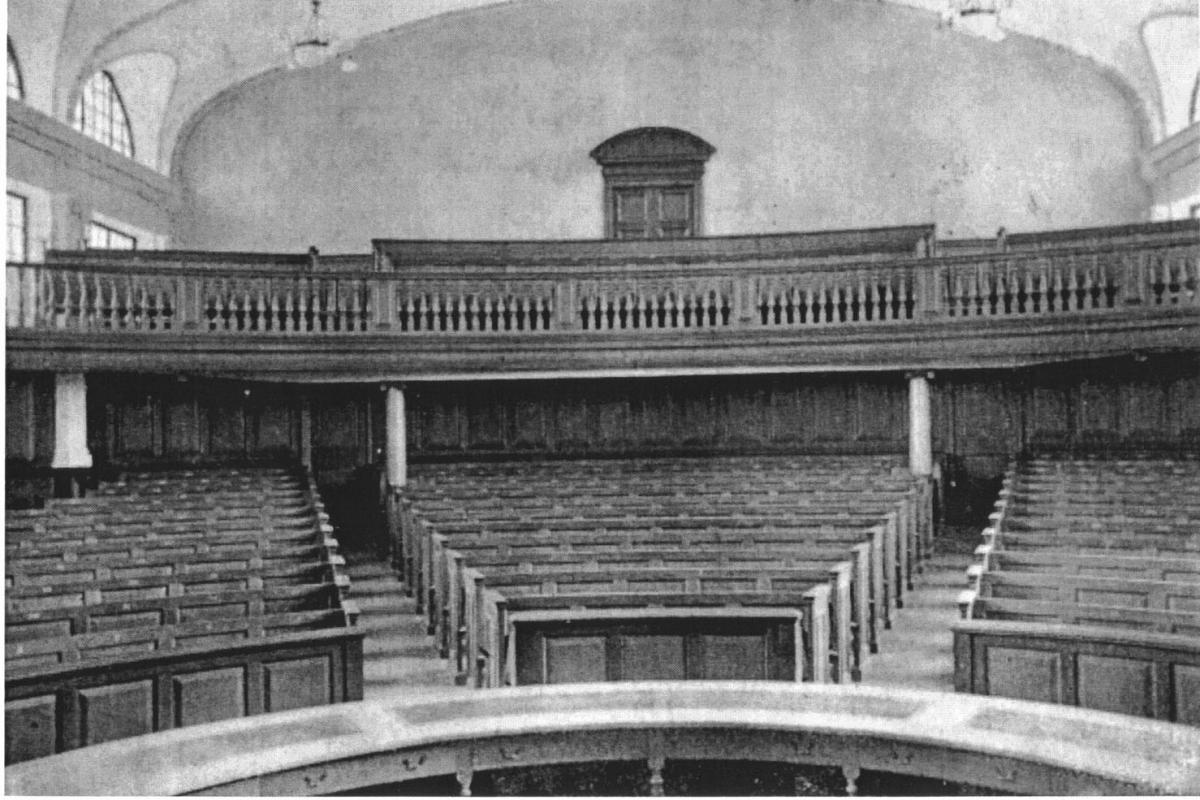

Building work began in February 1914, before the outbreak of war, and the total cost was £30,000. For their money, the miners got a stunning hall, offices and houses for their agents. The 300-seat council chamber became known as The Chapel, because of its similarity to Methodist chapels of the time. “Our early leaders were primate Methodists, ranters,” George Robson, a Durham Miners’ Gala organiser, told The Northern Echo in 2002.

Elsewhere, visitors marvelled at the 160ft-long façade, copper domed roof, grand stepped entrance, sweeping white marble staircase and oak panelled committee room. Even the gentlemen’s toilet, with its decorative green tiles, was designed with the miners’ aspirations of meeting coal owners on equal terms in mind.

“If the North Road hall was a statement that the union had arrived, this new hall, set in its own grounds resembling a coal owner’s estate, was an expression of permanence, power and prosperity,” Mr Hopper said.

On the approach were placed four statues, relocated from North Road: William Crawford, Alexander Macdonald, WH Patterson and John Forman. Born in Cullercoats in 1833, Crawford went down the mines aged ten. He served as agent, president and general secretary of the DMA and Liberal MP for Mid Durham from 1885 until his death in 1890.

Scotsman Macdonald worked in the pits from the age of eight and entered Parliament in 1874, one of the very first working class MPs. Though criticised by Karl Marx for his closeness to the Tory Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, Macdonald retained the support of the miners and was president of the Miners’ National Union until his death in 1881.

William Hammond Patterson was Newcastle-born and present at the 1869 Market Hotel meeting when what would become the DMA was founded. He succeeded Crawford as DMA general secretary in 1890 and is credited with introducing a more democratic style of leadership, before dying in post in 1896.

And finally, John Forman – he that had opened the North Road HQ in 1876. He was a Northumberland lad, and he served as DMA president from 1871 until his death in 1900.

Of course, it is not simply the building itself that makes for its significance, but also what has taken place within its walls: decades of negotiations over pay and conditions from Peter Lee and the Great Strike of 1926 to Sam Watson, who Mr Hopper blames for making Durham miners the lowest paid in the country by the middle of the century, through strikes of 1972, 1974 and 1984-5 and into hosting the 1990 NUM annual conference, which Mr Hopper calls Redhills’ “finest hour”.

Also of importance is what remains – archives, photographs and a 1943 letter from Joseph Stalin, thanking the miners for their donation of £1,500 for an X-ray machine.

The building, now Grade II-listed, has changed over the years. With the death of the coalfield, much of the business conducted inside concerns ex-miners seeking compensation for ailments brought about by their former occupation. Many of the offices are rented out – including to charities and Durham City MP Roberta Blackman-Woods. Outside stands a moving memorial to the 83 men killed in the Easington Colliery mining disaster of May 29, 1951. In 2012, a new sculpture was placed inside – The Miner, by Arthur Fleischmann.

What the future holds for a building described by Sunderland University mining historian Dr Stuart Howard as “probably the finest trade union building in Europe” is unclear.

A decade ago, it was mooted as a possible home for an elected regional assembly. There is talk of it becoming a heritage and exhibition centre, with a £2m application to the Heritage Lottery Fund in the pipeline.

With Durham County Council keen to leave its 1960s-built County Hall, perhaps the local authority could return to its red roots and make good use of the council chamber?

Mr Hopper, for one, is clear: “Whatever the future holds in these uncertain times we are determined that this magnificent building will remain a facility for the use of the Labour Movement and the people of Durham. It is our heritage and we must cherish it.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here