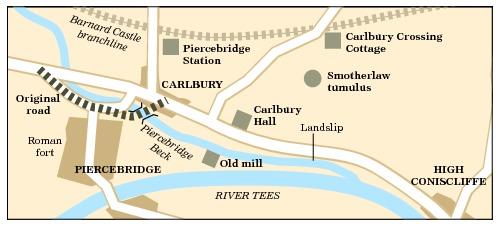

ON Monday, the A67 slipped quietly back into use more than two years after it was first closed by a landslip. The workmen have cleared the vegetation from the Tees bank between High Coniscliffe and Piercebridge and so travellers driving west along the treetop road from Darlington to Barnard Castle can see how sharply the land falls away to the river.

One Gainford resident, who comes into Darlington six times a week, estimates the detour caused by the closure has put at least 2,500 additional miles onto his car. Now with the road re-open, it is probably with much relief that drivers pass the scene of the landslip and few will think, as they hurtle down the hill towards Piercebridge, that they are going through the site of the lost hamlet of Carlbury.

Humans have lived in Carlbury since long before it was called “Carlbury”. A glance to the north reveals a mysterious-looking hillock, much ploughed around, which is called Smotherlaw. It is believed to be a Bronze Age barrow, or tumulus – a mound of stones piled over a grave a thousand or more years before the birth of Christ.

The name Carlbury is more recent, from Viking times. It was originally “Ceorlaburg” – the settlement of the ceorls, or karls. A ceorl was a free peasant, so the guess is that these people had earned the right not to be controlled by the Romans of Piercebridge, and so they lived in their own settlement on the high land outside the Roman fort.

On December 1, 1642, during the Civil War, a band of Royalists led by the Earl of Newcastle, stationed their canons on Carlbury’s high land, and fired them at the Parliamentarians, led by Colonel John Hotham, who had control of Piercebridge down below. The bombardment scattered the Parliamentarians, and allowed the Royalists to cross the Tees into Yorkshire unhindered.

The real spur for the development of the hamlet of Carlbury, though, was the advent of the railway. The branchline from Darlington to Barnard Castle opened on July 9, 1856, and the hamlet grew up to serve Piercebridge station with a pub, the Railway Inn, at its centre. The pub had quite extensive stables behind it, and it assisted in the distribution of goods coming from, and going to, the station.

In 1863, a quarry opened in Melsonby, and a train of 40 or 50 horsedrawn carts, each laden with stones containing copper ore, wound its way through Piercebridge and Carlbury to the station. The quarrymen unloaded their wagons so that the railway could take the ore to Liverpool for smelting, and then they retired to the Railway Inn to feast on a "cold collation" and on the delicious prospect of their imminent riches from the copper trade.

They toasted themselves, their diggings, their enterprise and their forthcoming good fortune.

"The party broke up highly delighted with the day's proceedings," concluded the Darlington and Stockton Times, but the venture was never a success – indeed the farmers who had loaned their carts for the opening day delivery were never paid for their hire.

Carlbury’s dramatic position high above the Tees appealed to Thomas McLachlan, who for 45 years was the manager of the National and Provincial Bank on Darlington’s High Row. In fact, Mr McLachlan was manager when the quirky N&P bank, designed by architect John Ross with three curious masks over its windows, was opened in about 1870 – it is now occupied by NatWest.

Mr McLachlan was a proud Scot. He loved Scottish folklore, and he loved Scottish scenes. In 1875, he commissioned Mr Ross to build him a Scottish baronial style mansion at Carlbury so he could imagine himself high on a Scottish mountainside overlooking a raging Scottish river.

Today, from the reopened A67, you can still see Mr McLachlan’s monogram in the stonework of Carlbury Hall. Above the main entrance is carved the Lachlan clan’s crest of a castle standing on a Scottish rock.

Just below Mr McLachlan’s Scottish-style hall was Carlbury Mill which, powered by the Piercebridge Beck on its way into the Tees, ground flour. But on Thursday, June 27, 1889, there was trouble at the mill: it caught fire. The flames were spotted at 11.15pm by a cyclist, Mr Nicholson, pedalling along the A67. He alerted the miller, Mr Patterson, and then he cycled off to nearby Piercebridge station in the hope that he could send a wire to Darlington for help.

But the station was closed. So Mr Nicholson had to pedal back past the burning building and three miles into Darlington where, at the Broken Scar waterworks, he located a telephone and summoned the brigade.

For two hours, the distraught miller could do nothing but watch his four-storey mill being ravaged by flames. The firemen arrived at 1.20am. “The roof had fallen in, and the accumulation of debris brought down the floors, all the machinery being destroyed,” reported The Northern Echo.

If you fancy a pretty, riverside walk through green pastures, there is a path along the Tees with a little footbridge over the Piercebridge Beck where you can still see the brickwork and cutwaters of the old mill race.

The hamlet of Carlbury survived longer than its mill. It lasted until just after the Second World War when the authorities decreed that the A67’s descent down the bank and its curve over Carlbury bridge was too dangerous. The hamlet, including the pub, was demolished, so that the road could be straightened.

Only the road bridge and Bank House survive, although the bridge is now so overgrown you can’t see it, and Bank House is hidden behind a screen of conifers. It would be impossible for a modern day photographer to replicate the scene of Carlbury on today’s front cover, but give the people of this hamlet a thought next time you are passing now that the road is reopened.

PIERCEBRIDGE station was built where the Barnard Castle branchline crossed the Roman road of Dere Street – Roman coins, urns and even human remains were unearthed by the workmen.

The station closed to passengers on November 30, 1964, and was demolished, although the station house survived and is now a private house. The level crossing keeper’s cottage at Carlbury is also now in private hands.

Both of these houses possess one of Memories’ favourite things: a Stockton and Darlington Railway property plaque.

For an unknown reason, in the late 1850s, the railway allocated a letter to each of its branchlines – the Barnard Castle line was F – and then attached an individually-numbered plaque to each of its residential properties.

F1 was stuck on the first property on the line, which was a crossing keeper’s cottage at Honeypot in the Rise Carr area of Darlington. F2 was on the Mount Pleasant crossing cottage near today’s West Park Hospital. F3 can still be seen on the Carlbury crossing house, and F4 is just about visible on the Piercebridge station house.

The line terminated in Barnard Castle, where F11 can still be seen attached to a railway house in Galgate.

A couple of years ago, Memories started a series tracking the railway plaques. We looked at the A line, from Middlesbrough to Redcar, the B line, from Middlesbrough to Guisborough, and the J line up Weardale, from Howden-le-Wear to Frosterley. Then we ran out of steam. Perhaps we should start up again with the F line.

IF you have any information or memories to add to today’s article about Carlbury and the railways, we’d love to hear from you.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here