SEVENTY years ago today, people of the region were waking up, after six long years of fighting for freedom, to the reality of peace, although many of them had slightly fuzzy heads.

They had been waiting anxiously for several days for the German surrender to become official and for the war to be declared over, and even at the last minute, there was a hiccup. The German representatives of Grand Admiral Karl Donitz, who had been president for a week following Adolf Hitler's suicide, signed surrender documents at Reims in France on May 7, 1945, announcing formally that their nation would stop fighting at 11.01pm on May 8.

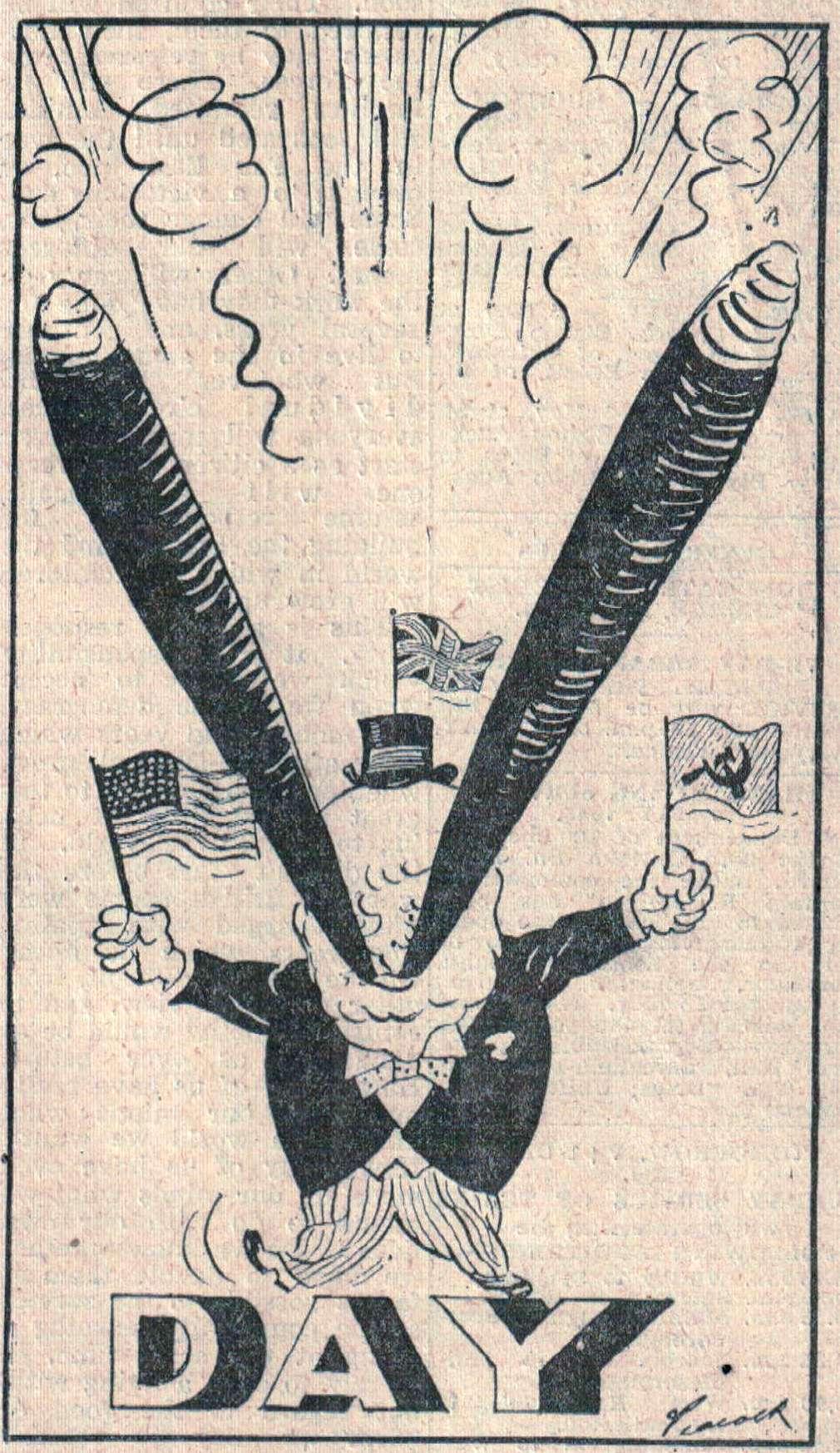

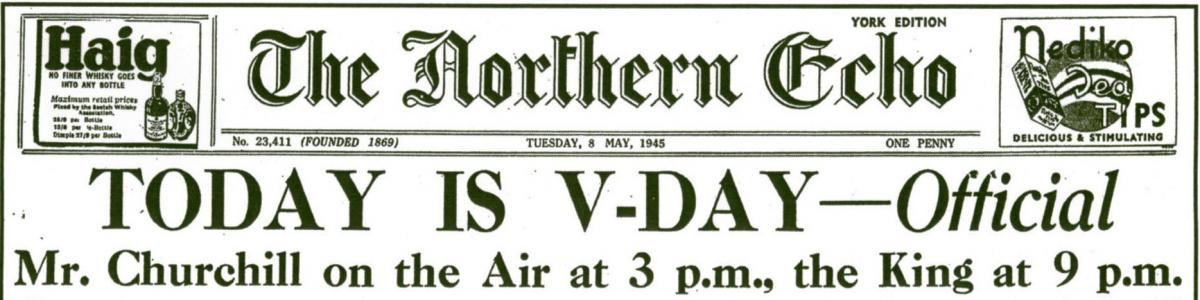

This was enough for The Northern Echo to declare in enormous letters on that morning's front page: "TODAY IS V-DAY."

Yet even as the paper was being printed in Darlington, the Russian leader, Josef Stalin, was refusing to accept the Reims surrender. He regarded it as a "preliminary protocol", and demanded that a complete surrender could only be signed in the German capital of Berlin. He got his way, with pens going to paper late on the evening of May 8, and so many parts of the former Soviet Union celebrate Victory Day on May 9 – a full 24 hours after the rest of Europe.

So despite The Northern Echo's large headline, many people on the morning of May 8 were uncertain how to behave – a part from in one coastal town.

"In Hartlepool," reported the Echo, "the noisiest part of the day was at the very beginning when, at midnight, ships in the harbour rent the air with the victory sign on their sirens, combined with bursts from machine guns, which sent tracer bullets in a red stream into the sky."

Other less presumptuous towns spent the morning quietly preparing for an imminent celebration.

"Darlington today is lavishly be-flagged for victory," said the Evening Despatch, the Echo's sister paper. "Every main street in the centre of the town is gay with hunting and the flags of the Allies and, with the works and schools closed, many people were about from an early hour.

"Almost every house boasts a Union Jack, strips of red, white and blue, and photographs of the King and Queen. In some places, victory decorations are coupled with large homemade posters welcoming home men who have only recently returned from German prison camps."

It wasn't, though, until about midday on May 8 that people convinced themselves that this really was it, especially when they heard that Prime Minister Winston Churchill was due to take to the wireless at 3pm. His address was relayed through loudspeakers to the thousands of people who had thronged to London's Trafalgar Square, although in the North-East, the weather was putting a dampener on the impromptu celebrations.

"Redcar, Saltburn and Marske were gaily decorated but continuous rain drove jubilant people indoors," said the Echo.

It turned out nice, though, in time for the evening's street parties.

But, while there was undoubted joy, that joy was not unbridled. It is true that bells, free from their wartime muffles, rang from every church steeple, and it is also true that town centres, free from the blackouts, were blazed in floodlights. It is also true that by day, the streets filled up with feasting children, and by night, they were taken over by young people, many of them in service uniforms, "making whoopee", to use an Americanism that had come over with the GIs.

But it is also true that VE Day was a day of sadness. About one per cent of the British population – 67,000 civilians and 380,000 soldiers – had been killed during the war. VE Day was a natural time to mourn them – particularly as the war the world over was not yet over.

In Middlesbrough, the mayor, Robert Ridley Kitching, made a brief address from the town hall balcony. "He appealed to the people to take their share in the building of a better Middlesbrough, a better England, and a better world," reported the Echo. "The townspeople stood in reverence for one minute to those who had made the supreme sacrifice."

Stockton was similarly restrained. "The mayor (Coun A Ross) had a son in the Far East," reported the Darlington and Stockton Times. "He asked everybody to go back to work after the holidays and to work as hard as ever to assist the war against Japan. We had, he said, got over the first hurdle and we must work religiously until we had surmounted the second."

And how must poor Mrs M Sains, of 5 Oxford Street, Eldon Lane, have felt on this day of all days? For it was on VE Day that the Echo reported that her son, George W Sains, 18, of Signal Company, US Third Army, had been killed.

In Whitby, a soldier drowned while celebrating his escape from hostilities, and at Winston, on the edge of Teesdale, an Army lorry overturned, hospitalising three soldiers and killing Sgt-Maj Newall-Smith, a female member of the ATS.

The Echo reported that York "was strangely quiet, in striking contrast to the hilarity of Monday night, when Canadian and French airmen joined with English servicemen and women and their friends in making considerable 'whoopee'."

Durham City was also described as "quiet", although "the undergraduates, with a preponderance of women, marched into the Market Square in the forenoon and danced round the policeman seated in the traffic control kiosk."

Other places were not so reserved. In Great Aycliffe, for example, there was a baby show and even an ankle competition on the green (a line of women sat on a bench with the upper three-quarters of their bodies shrouded by a sheet showing only their ankles which were then judged on their shapeliness).

As the evening wore on, though, the beer took its effect and the bonfires burned, usually with a guy in the form of the Fuhrer on top.

"Effigies of Hitler, hanging by the neck with his paintpot and brush, were a feature of Fishburn V-day celebrations," said the Echo of the village's three bonfires. "Another topical tableau was that of a model coalmine decorated with coloured lights with the slogan 'Fishburn has done its bit' in recognition of the local colliery having an output which is always on the target."

Hitler, poor fellow, had a rough night, being burnt in many different places.

Barnard Castle's celebrations "culminated at about midnight when a stagecoach in which Hitler lolled by the window was trundled into the market place and set on fire. There was a terrific blaze, and the figure inside went off with a bang. It was a satisfactory finale."

In Darlington, the celebrations became boisterous.

"Thousands of people lined High Row and adjoining thoroughfares to see the floodlighting of the town clock and St Cuthbert's Church," reported the Echo. After the restrictions of the blackouts, the buildings were bathed in light from 10pm until dawn. Two searchlights created a V in the sky, and flashing beacon was installed on High Row.

"The Market Place was crammed with high spirited young people," said the paper. "Parties of soldiers, usually accompanied by many children, marched up and down various steers singing popular songs, with an occasional mock charge."

They climbed poles, ripped down flags, and used two Belisha beacons requisitioned from a road crossing in a football-cum-rugby match "that made Sedgefield's Shrovetide game tame by comparison".

It went on long into the night, and even the weather played its part. "Those who sought their homes after midnight had their way illuminated by an amazing display of sheet lightning while thunder roared in the distance recalling to the more imaginative the flashes of the worst nights of the air raids," said the Echo.

This, though, was only the beginning of the "V-period". The following day in Darlington, for example, there was rollerskating in South Park on the illuminated rink until 10pm, after which there was dancing. There was more dancing in the Market Place, accompanied from 9pm to midnight by a military band, and "after midnight, records amplified through loudspeakers".

Perhaps the surest sign that life was beginning to return to normal came in the edition of the Echo – May 9, 1945 – which carried these VE Day reports. There, tucked away, at the foot of a page is the weather forecast. It had disappeared from newspapers at the start of the war because the government believed that if the enemy knew the forecast for the Tees Valley or Tyneside, it would be a boost to their intelligence. Now, after six long years of fighting for freedom, the forecast was back, although it didn't make good reading: "Occasional thundery rain..."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel