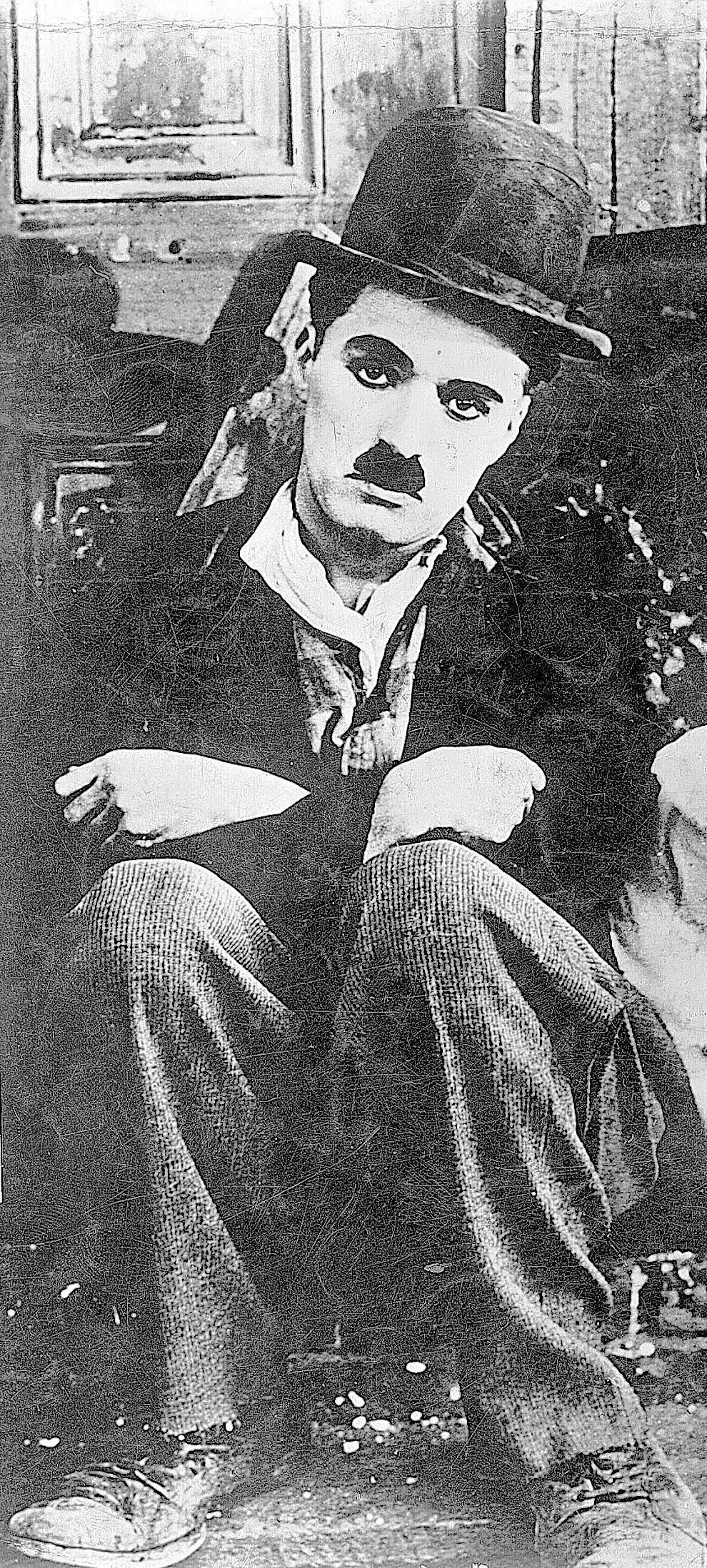

The sun shines bright on Charlie Chaplin

Before they send im

To the Dardenelles

His little baggy trousers they want mendin’

Before they send im

To the Dardenelles

NINETY-FIVE-year-old Morris Taylor bounces around on a sofa in Thornaby-on-Tees as he sings, his rich voice with just a hint of a Welsh lilt booming out from beneath his Kiwi peaked cap, the song his father used to sing him. On the other side of the room, Morris’ sister, Gwynneth, adds a few high notes to the well-remembered family favourite.

Today is Anzac Day. In Australia and New Zealand, it is remembered with as much solemnity as we mark Remembrance Sunday. Today is a special Anzac Day – it is exactly 100 years since the Anzac forces landed on the Gallipoli peninsula in Turkey which guards the Straits of the Dardenelles.

For Morris and Gwynneth, it is also a special day because, before dawn 100 years ago, their father, Pte Harry Taylor, landed as part of the Anzac force amid carnage. He was badly injured before the day was out – shot through the leg.

“The bullet entered here and came out here,” says Morris, indicating with his long fingers to the back and front of his leg. “He had scars on both sides, and when I was a small boy, I remember him calling out ‘my leg’s given out’, and we had to get him home.”

Pte Harry Taylor was with the Anzac forces because, in the 1860s, his father, Henry, had emigrated from Catterick in North Yorkshire to the north island of New Zealand. He worked at first for the Maoris who, out of gratitude, gave him 365 acres of land – one for every day of the year – near Whangarei.

There in 1891, Harry was born. “My father was serving his time as a wheelwright when he was called up,” says Morris, who is incredibly spritely and sharp for a nonagenarian. “He was away on a training mission with the Territorial Army when New Zealand went into the war, and he never went home until 1925.”

His records indicate that he joined the New Zealand Expeditionary Force on January 1, 1915, and sailed to Alexandria in Egypt, where the Kiwis joined with Australian troops to form the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (Anzac). The Anzacs were expecting to go to France to serve on the Western Front, but the Allies wanted to open up an Eastern Front, partly to distract the Germans and partly also to open a sea route through the Dardenelles into the Black Sea so that Russia – Britain’s ally – could get its navy out.

But the narrow Dardanelles were guarded by the Gallipoli peninsula on which the Turks were well dug in. In February 1915, Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, thought that the British navy could bombard its way through the straits, but the Turks rained so much shellfire on the ships that they had to retreat. It was decided that a land invasion was the only way to clear the Turks from the peninsula, and the boys from Down Under were called up.

They were supposed to land from their rowing boats at what is now called Anzac Cove before daybreak on April 25. It was their countries’ first major conflict, and it was a disaster. They drifted a mile too far north and instead of beaching on sand, they found themselves faced by towering cliffs and impenetrable ravines.

“They couldn’t get out of the water to start with and then they had the cliffs to contend with so they didn’t make much headway inland,” says Morris.

The Turks were better armed than expected. Allied orders became confused and when they did make a breakthrough, they failed to press it home. As night fell, Allied commanders vacillated about whether to order a full scale withdrawal or whether to dig in and stay put.

At last, the order came through to dig in. Of the 16,000 men who landed on Gallipoli that morning, about 1,000 had been killed and at least 2,000 of the wounded had been evacuated from Anzac Cove – with many more lying injured on the battlefield awaiting assistance.

Somewhere amid this carnage lay Pte Harry Taylor, mown down by a machine gun. He was picked up and sent to a hospital in Surrey to recover. His stay was long enough for him to form an attachment with a nurse, Elizabeth Morris from Ebbw Vale in Wales. Twice he was sent back to the Western Front only to be bombed and gassed so badly that twice he had to come to Elizabeth for repairs.

He was demobbed on March 14, 1919. His records show that he received £709 eight shillings and two pence for his war service: 1,493 days regimental pay at five shillings a day plus 1,462 days field allowance at 1/6 a day, less £2 15s 10d for cables home and £3 2s for “hospital stoppage” – he appears to have had money deducted for being too injured to fight.

He married Elizabeth in Wales on April 19, 1919, and on March 20, 1920, Morris was born in Ebbw Vale.

But Harry was struggling to settle in Elizabeth’s Welsh steeltown, and when the New Zealand government announced it was ending its free scheme to repatriate soldiers stranded in Europe, they decided to climb aboard the last ship home.

“I remember we sailed from Southampton on the SS Ruahine, and we went the back way to New Zealand, through the Panama Canal and past Pitcairn Island,” says Morris, who was five and wide-eyed with wonder. “It was a mail ship, and it stopped off Pitcairn and the islanders came out with their letters. The passengers were throwing money off the side of the ship and they were diving for it.

“At Wellington, we caught a big Yankee train, with a cowcatcher on the front, and a great chimney, and the seats were all wooden and you could put them backwards or forwards – I had never seen anything like it.”

They arrived at the family farm at Pukekohe, but poor Elizabeth was desperately homesick. Two years later, the Taylors returned to Great Britain – “I remember stopping at Naples and Vesuvius was smoking”, says Morris, drawing a cloud in the sky with his hands.

But, in the grips of the Great Depression, Ebbw Vale was even more grim than before. “My mum had two cousins who lived in Middlesbrough – in fact, the story says Uncle Will walked from Ebbw Vale to Middlesbrough to find work,” says Gwynneth.

Harry, suffering from his leg and shellshock, followed them. He was taken on by Dorman Long and called his family to the North-East – Gwynneth was born in Middlesbrough in 1933 although it wasn’t until 1935 that they could afford to move out of their rented rooms.

Life was hard, but not without its moments. “When the rugby was on the TV and the All Blacks were playing Wales, there was hell on in our house,” says Morris. “Dad used to do the haika for us and if the All Blacks scored, my mother hit him on the head with a newspaper.”

Both Gwynneth and Morris are immensely proud of their Anzac father. “He was so badly shellshocked that some days he could hardly speak,” says Gwynneth.

“But he liked the horses – Scobie Breasley was his favourite jockey,” says Morris, who followed his father into the steel industry.

“And he liked his pipe and he liked a drop of rum in his first cup of morning coffee, and a slice of cheese on his porridge,” says Gwynneth, who worked as a nurse.

When Harry died aged 78 in 1969, the New Zealand government paid for his headstone in Acklam because it recognised that his health had suffered because of his war service.

“My father never missed Anzac Day,” says Morris. “It was a day of silence and remembrance. He never talked very much of his experiences, but I remember a song that he sometimes sang about Charlie Chaplin...”

THE ALLIES finally withdrew from Gallipoli on January 9, 1916. The campaign had cost 120,000 lives. Of the 8,500 New Zealand soldiers who had landed, more than 2,700 were killed and 4,500 were wounded. “Anzac Day”, April 25, was first commemorated in 1916.

SCOBIE BREASLEY was an Australian jockey who found great success in England in the 1950s and 1960s. He won the Derby twice, the Prix de l'Arc de Triomphe once, and was champion jockey in 1957.

CHARLIE CHAPLIN was a controversial figure during the First World War. He became globally popular in 1914 with his Tramp character, which was so liked by the troops that the films were played in army hospitals. However, despite being British, he remained in Hollywood and did not enlist, causing right-wing newspapers like the Daily Mail to label him “a slacker”. When the US entered the war in 1917 and he still didn’t join up, he was sent thousands of white feathers.

He remained popular with the troops, but they did parody a music hall song called Red Wing to reflect the fact that he was never going to find himself at war in the Dardenelles. The parody features in the film Oh What A Lovely War.

ALSO on April 25, 1915, the “boys of Bede” were caught up in the Battle of Gravenstafel Ridge, near Ypres. As Memories told last week, 102 students and newly qualified teachers from the College of St Hild and St Bede, left Newcastle station on April 19 and were immediately pitched into battle. Of those 102, 58 were casualties within 24 hours at the front – 17 dead, ten wounded, 31 missing, many of whom were captured. At the end of the war, of the 102, 25 were dead, 27 wounded, 33 were prisoner, and then three more died of disease.

To remember the 100th anniversary of their sacrifice, a service is being held at the College War Memorial today at 6pm. All are welcome.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here