MEMORIES 225 told of the role of Brancepeth Castle, near Durham City, during the First World War, and Stanley Layfield has got in touch to tell of its importance during the Second World War.

A large army camp of more than 100 huts spread south from the castle down Tripsy Bank – the A690 – towards Willington.

“It was an infantry training command and all the new recruits for the Durham Light Infantry and the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment would come in for their first six weeks basic training – infantry drill, rifle and bayonet training and camouflage techniques,” he says. “Those that were staying in the infantry then a further 12 weeks core training – route marches, firing training.

“There were more than a thousand men from the DLI and DoW there at any one time.

“In October 1942, I was sent from Darlington to Brancepeth Castle to join up. For my six weeks’ training I lived in the castle, and the rest of my time I was in a squad hut with 30 men.”

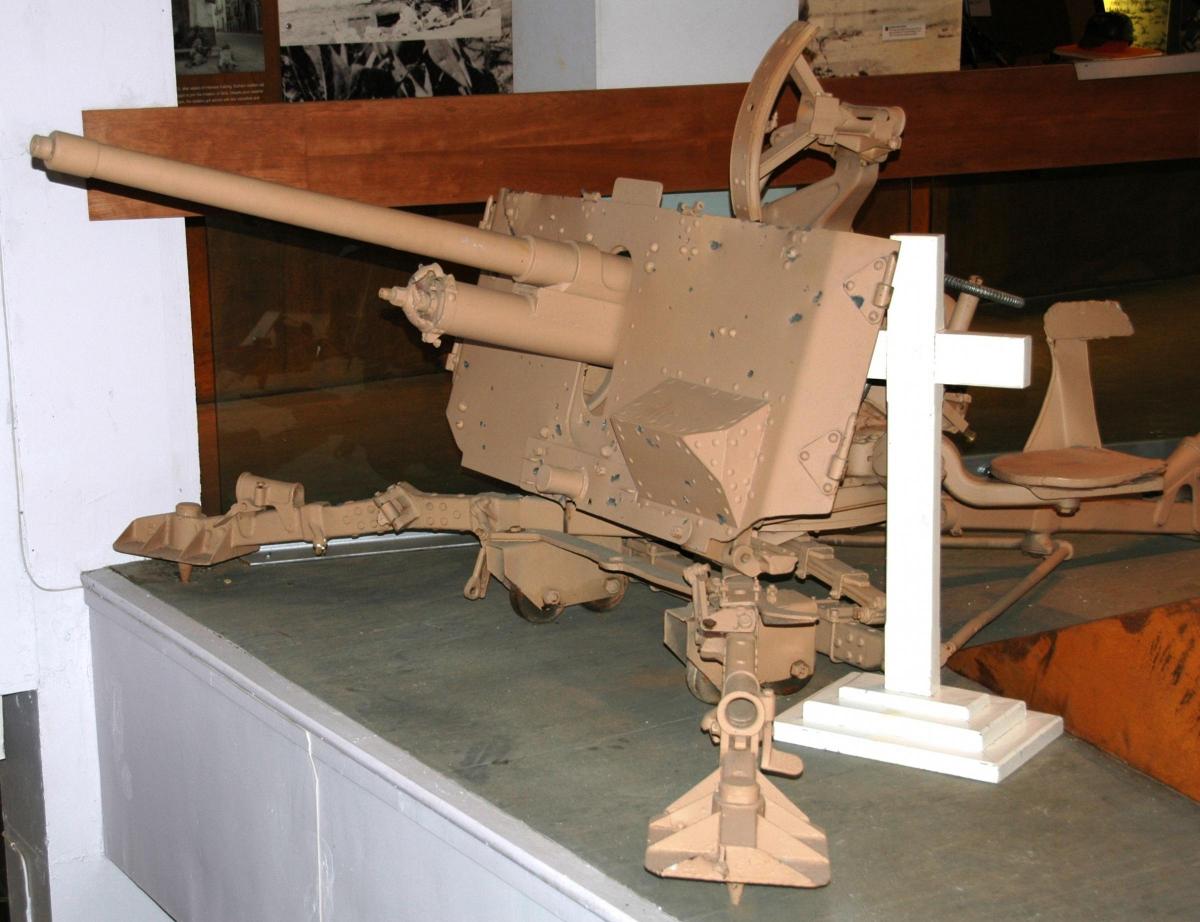

After serving with the 10th DLI, Stanley returned to Brancepeth in 1944 to become an instructor, a role he had for three years. During his time at the castle, he remembers Wakenshaw’s Gun having pride of place in the middle of the courtyard.

This gun is now in the DLI Museum in Durham City, and it was last fired on June 27, 1942, by Pte Adam Wakenshaw.

Wakenshaw came from Newcastle, joined the DLI at the outbreak of war, and survived Dunkirk. By the spring of 1942, he was with the 9th DLI in Egypt where they were trying to halt a German advance. At 5.15am on June 27, the DLI’s two-pounder anti-tank guns scored a direct hit on a German tracked vehicle which was towing a machine gun.

This encouraged the enemy to pour its fire on the Durham guns until they were all silent. Wakenshaw, 27, was seriously injured, his left arm blown off at the elbow.

Without the anti-tank fire to worry about, the Germans tried to reach their tracked vehicle which still had a machine gun on it. The main body of the DLI was about 200 yards from that machine gun, within easy range.

Seeing the danger, Wakenshaw crawled back to his gun and, with the help of Pte Eric Mohn, he loaded the gun with his one remaining arm and, despite coming under heavy fire, let off five shells and destroyed the enemy vehicle and gun.

The Germans returned fire, killing Mohn outright and further wounding Wakenshaw.

Amazingly, he dragged himself back to the gun, loaded it once more, and was about to fire when a direct hit to his ammunition finally killed him.

Without anything to hold them up, the Germans over-ran the DLI, killing 20 and capturing 300. But not only had Wakenshaw shown immense bravery in holding the enemy up, he had also saved bhis company from coming under fire and bought time for their retreat.

He was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross, which his widow, Dorothy, and their young son collected from Buckingham Palace on March 3, 1943 – the last time Dorothy had seen her husband had been in February 1941 when he’d been allowed a few days compassionate leave following the death of their seven-year-old son, John, in a road accident.

In the immediate aftermath of the battle, Wakenshaw was buried beside his gun. In 1943, he was reburied with full military honours in El Alamein War Cemetery in Egypt and his “twisted and shell-shattered” gun was placed in the middle of the cemetery. It was later brought home to Brancepeth, as Sidney remembers, and is now in the museum.

The camp itself remained until the early 1960s when its site was open cast for coal. In the mid 1960s, it was returned to farmland.

There are a couple of officers’ houses, now in private hands, that remain from the military days, but looking at the landscape you cannot tell that there was either a coalmine or a camp holding 1,000 soldiers was on the field down Tripsy Bank.

LUCK'S SQUARE in Darlington featured in Memories 223 – it was behind Darlington Town Hall, where the new education offices have recently been built. It was a late Victorian square of pretty substantial brick homes built by shopkeeper Richard Luck on top of the Bishop of Durham’s old haunted palace. The square was cleared in 1960 although the ghost – that of Lady Jarrett – is said by some to haunt the area still.

“I remember No 3 Luck's Square,” says Avril Gibson of Darlington. Her family, beginning with her great-grandfather George Judge Morris, lived there from at least the 1890s.

“It had two big front rooms and a big kitchen at the back. My great-grandmother Harriet had 14 children there – three died in the First World War.”

The eldest of the seven daughters was Avril’s grandmother, Catherine, and the square remained the family home until it was demolished.

“I remember going through that archway and playing in the square,” she says, “but I never saw any ghosts in there.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here