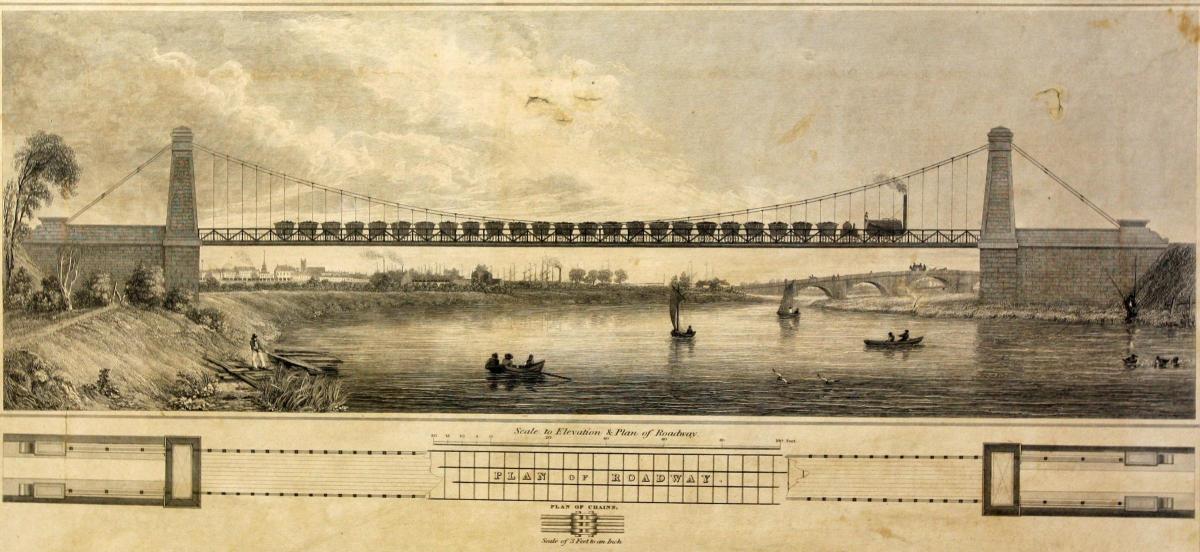

MEN sail in little boats on the Tees as seagulls swoop and ducks dabble, and one galloshered man on the bank drifts a net across the surface of the water in hope of catching fish – surely he is in danger of also ensnaring a rowboat or two. Nobody bothers.

In the distance, chimneys smoke proudly and the masts of ocean-going ships stand nobly. And across the middle of it all clatters a steam engine pulling 24 wagons piled high with coal. Again, nobody notices.

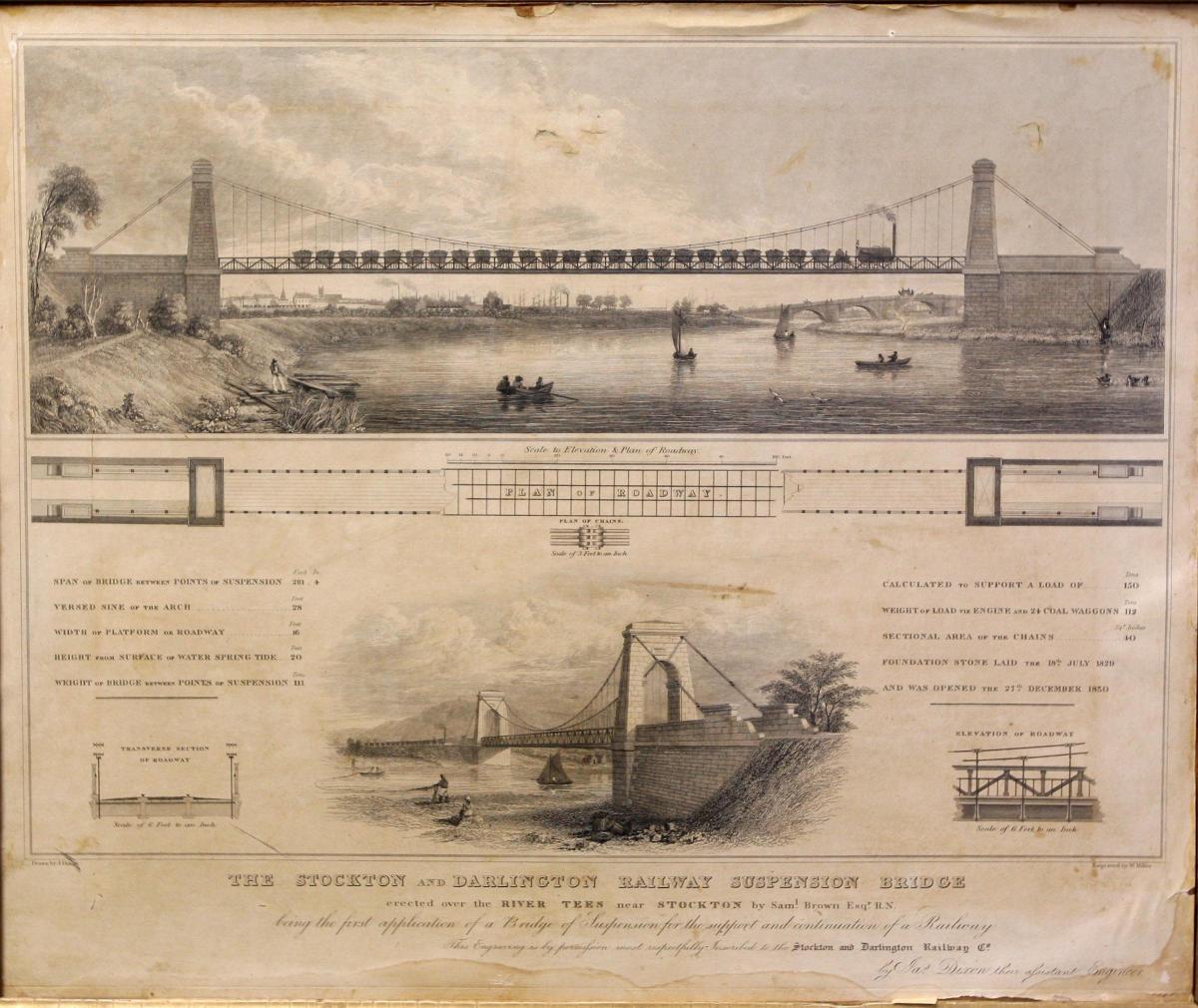

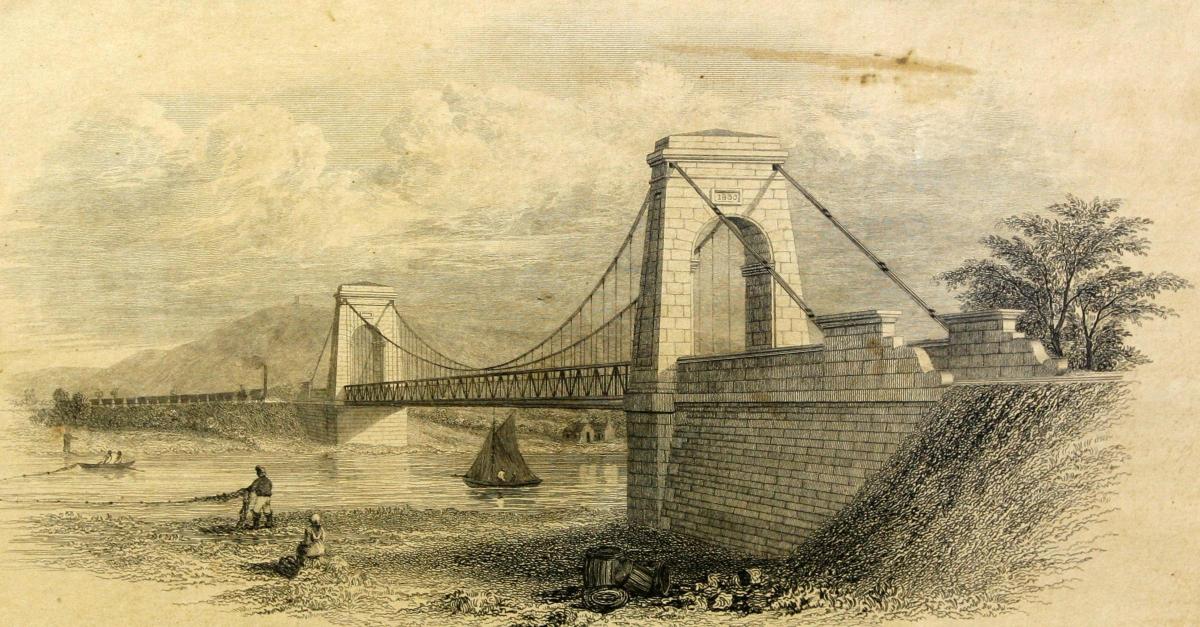

This pretty industrial scene is on a rare print which is one of the items for sale at next Saturday’s Durham Book Fair. It is an extremely historic item – the flowery lettering at the foot of the print proclaims that this is “the first application of a Bridge of Suspension for the support and continuation of a Railway”.

In less flowery language, this was the world’s first railway suspension bridge.

But on the day the bridge opened, which the print records as December 27, 1830, the language was probably anything but flowery. It is a fair bet that among the railway pioneers, it was unutterably foul.

Because – and the souvenir print doesn’t say this – the world’s first railway suspension bridge was a disaster.

Work on the bridge commenced in October 1828 when the coal-carrying Stockton and Darlington Railway decided to extend its tracks from Stockton over the Tees to a new port nearer the mouth of the river. That new port was initially called Port Darlington although it grew to become Middlesbrough.

The railwaymen – led by Joseph Pease of Darlington – initially wanted to build a traditional stone arched bridge over the river, but the shipping authorities argued that this would endanger their vessels. Mr Pease called in Captain Samuel Brown of the Royal Navy, an intrepid sailor who had grown tired of his hemp ropes snapping and so had invented the metal chain. With all his ships tied up tightly by chains, the captain turned his attention to dangling bridges from his metalwork. The first of his suspension bridges opened over the Tweed near Berwick in 1820, and his £2,200 Tees bridge was ready for testing on December 10, 1830 – nine months after his suspension bridge in Montrose had collapsed, drowning three people.

The Tees test didn’t go much better. As the first engine, pulling 16 coal trucks, edged onto the bridge, the deck wobbled and shook, and the pillar on the Yorkshire side swayed and cracked. As the train neared the centre, the deck rose up in the middle, creating a mini-mountain, with eight trucks going up the Durham slope while, simultaneously, the other eight rolled down the Yorkshire side.

The coupling in the middle snapped, and while the front eight wagons and the engine proceeded across to Yorkshire, the eight rear wagons ran away, speeding down the hump into Durham.

Hurriedly, the railwaymen propped the bridge up with wooden “starlings”, or piles, and on the opening day, hundreds of people were safely transported across the 281ft deck to Port Darlington.

But, boy, did it sway. It swayed so much that soon orders went out to chain the trucks 27ft apart so that weight was distributed evenly across the bridge.

Not everyone was satisfied with this approach, though. One driver was so worried that as he neared the bridge, he set his locomotive to “crawl” and leapt out of the cab. He dashed across and safely waited on the other side for his train to make its perilous path over the swinging, clanking bridge.

Then he jumped back aboard and, full steam ahead, drove for Port Darlington.

The world’s first railway suspension bridge was such a disaster that in 1842, Robert Stephenson started building a conventional bridge beside it to take the traffic. The suspension bridge was demolished in 1880, although its piles were re-discovered in 2009 near the rail and A66 road crossings of the Tees.

The souvenir print doesn’t portray any of this. Instead it shows the bridge’s masonry piers being true and upright and that the deck is straight and level as the heavy train goes across it with life around it – the sailors, the rowers, the seagulls and the ducks – without batting an eyelid.

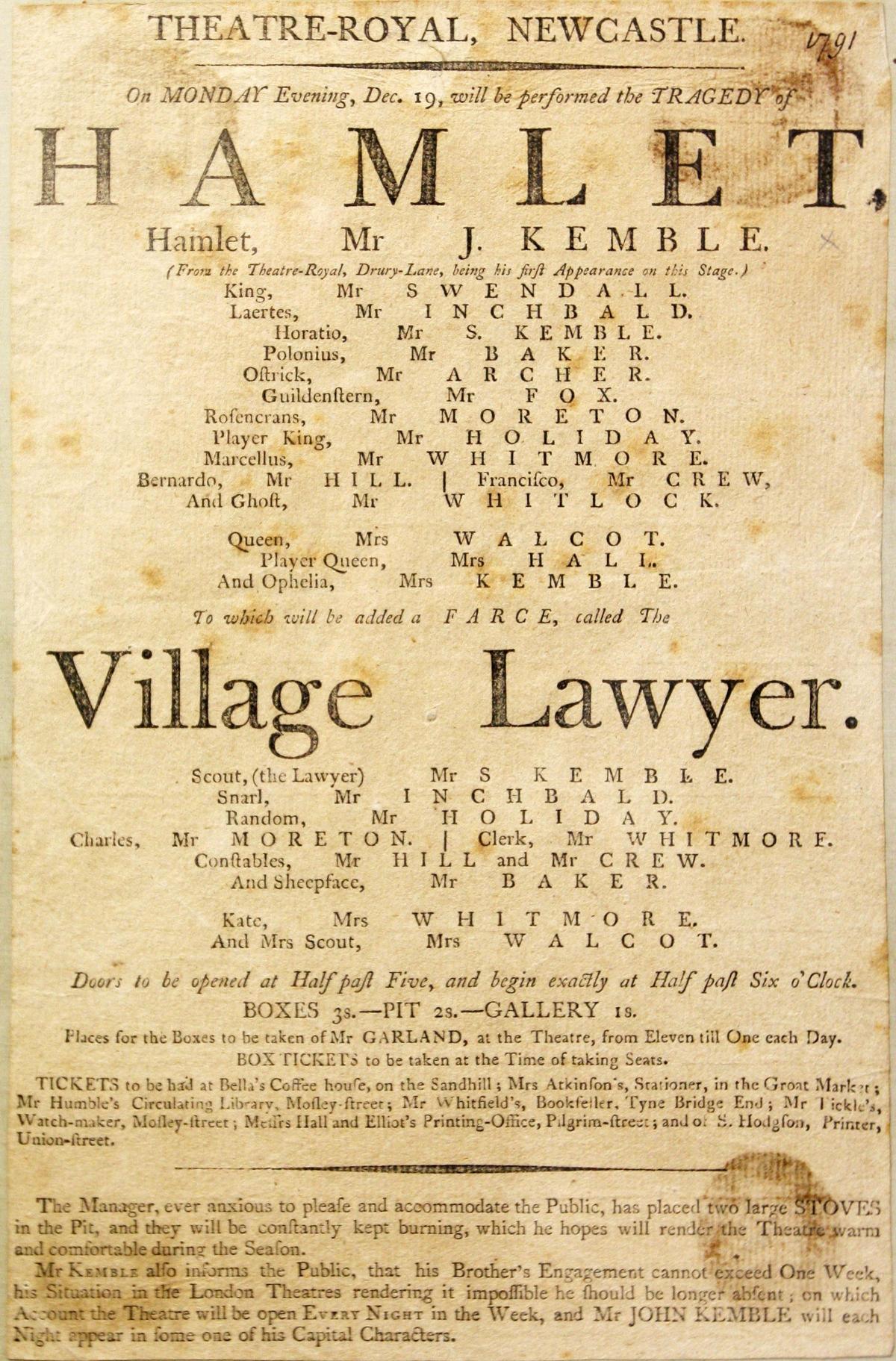

ANOTHER fascinating item at the Durham Book Fair is this December 1791 poster advertising a performance of Hamlet at the Theatre Royal, Newcastle.

In the lead role was John Kemble, perhaps the greatest actor of his day making his debut in Newcastle, but the main attraction was the heating system.

The poster, or handbill, says: “The manager, ever anxious to please and accommodate the public, has placed two large stoves in the pit, and they will be constantly kept burning, which he hopes will render the theatre warm and comfortable during the season.”

The manager was Stephen Kemble, the younger brother of Hamlet. The Kembles’ parents were travelling actors, and Stephen – all 6ft, 31 stone of him – made a big impression on the London stage. Unfortunately, it was not always a favourable impression and so, with his wife Elizabeth, he retreated to the provinces.

He must have been a man of immense energy because he managed theatres across Scotland and the north of England, including the Durham circuit – this meant he had theatres in North and South Shields, Sunderland, Stockton, Northallerton and Scarborough as well as Saddler Street, Durham, under his control.

His principal business was the Theatre Royal, Newcastle, which opened in 1788 and which he took over in 1791. For the week before Christmas, he produced a theatrical extravaganza – complete with two large stoves to ward off the Tyneside snows.

In the production of Hamlet, Stephen played Horatio, and Elizabeth – herself an actress of great repute despite her bad temper which once led her to bite a co-star on stage – appeared as Ophelia.

But brother John in the lead role was the undoubted star. John was an extremely well regarded actor at Drury Lane, London, at the height of his fame, despite being troubled by asthma, alcohol and opium. He later became a controversial theatre impresario, sparking many days of rioting when he redeveloped Covent Garden so that it had an extra 26 luxurious private boxes for his favoured wealthy patrons but far fewer cheap seats.

John is buried in Westminster Cathedral where there is a life-sized statue of him.

Stephen retired from Newcastle in 1806 after creating the Theatre Royal’s reputation as the leading provincial theatre in the country. He settled in Durham where he had an interest in the Saddler Street theatre. He struck up an unlikely friendship with the Polish dwarf, Count Jozef Boruwlaski – six-footer Stephen towered over the 28 inch Jozef so the pair were known as “Little and Large”.

Stephen died in 1822 and was buried in Durham Cathedral. When Jozef passed away in 1837, he was buried beside him so the double act could continue in the afterlife. Elizabeth, who died in 1841, lies on Stephen’s other side.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here