THE Heugh at Hartlepool juts out defiantly into the biting wind whipping off the North Sea. Today, looking south to Saltburn through the white-capped waves there is nothing more threatening that a flotilla of turbines on the water and a squadron of seagulls trying to land in the crosswind on the green beside the lighthouse.

But 100 years ago on Tuesday, it was very different. Shortly after 8am, from about the direction of the Seaton Carew turbines, three German warships appeared out of the mist, and from a couple of miles out unleashed a terrifying bombardment on the unsuspecting town.

Simultaneously, about 40 miles down the east coast, two more members of the German battlecruiser squadron turned their guns on Scarborough for half-an-hour before sailing north to Whitby and pounding it for seven minutes.

In the course of an hour, the five warships fired about 2,000 shells at the three seaside towns. They killed about 150 people, nearly all civilians, and wounded more than 500 – even today, we don't know the precise figures.

And then they disappeared back into the mist.

WHY?

Primarily, the Germans wanted to draw sections of the British fleet into the open sea where they hoped to destroy them, but they also wanted to awake British civilians to the horror of war in the hope that the British would turn against their government.

Although the British made much of the Germans attacking civilians, Hartlepool, with its ship-building docks defended by some soldiers and artillery, could have been classed as a legitimate industrial and military target. Scarborough, a wealthy, fashionable resort, was undefended, although modern research suggests the Germans may have thought there was a military target at the castle.

HOW

Rear Admiral Franz Hipper, commander of the German battlecruiser squadron, had asked permission of Kaiser Wilhelm on November 17 to send a submarine, U-17, to secretly investigate the defences at Hartlepool and Scarborough. It found nothing to concern the Germans, so early on December 16, the squadron slipped out of its base at Wilhemshaven, near Hamburg, and sailed towards the North-East. There were probably other vessels from the Hochseeflotte – High Seas Fleet – on Dogger Bank, watched over by a couple of British battlecruiser squadrons.

The British probably had about 25 warships in the area, and they exchanged fire as the Germans' ten ships sailed through.

As Hipper's ships neared the coast, three peeled off to attack Hartlepool, and another three went south to Scarborough and Whitby.

After their bombardments, they re-united and sailed for home, with British warships having visual contact with them for 50 minutes as they went across the Dogger Bank.

BRITISH INACTION

The British had cracked Germany's primitive code and knew on December 14 that the battlecruiser squadron would soon be leaving Wilhemshaven. The British were reluctant to act on this intelligence because doing so would have warned the Germans that the code had been broken, although warnings were issued to North-East coastal towns from midnight on December 16. At 4.30am, live ammunition was issued to the Hartlepool gun batteries at the Heugh and the lighthouse, so someone somewhere was taking the threat seriously.

On Dogger Bank, the British were reluctant to confront the enemy ships because they did not know what they were up against. They feared they would be outnumbered and destroyed.

The Royal Navy didn't want to risk any ships preventing what the British Government regarded as, according to The Northern Echo, "a mosquito attack – very annoying, but otherwise futile".

Immediately after the bombardments, an official British statement said: "The admiralty take this opportunity of pointing out that demonstrations of this character against fortified towns or commercial ports, though not difficult to accomplish, provided that a certain amount of risk is accepted, are devoid of military significance. They may cause some loss of life among the civil population and some damage to private property, which is much to be regretted, but they must not, under any circumstances, be allowed to modify the general naval policy which is being pursued."

This lack of action was taken badly in the North-East.

THE WEATHER

A contributory factor to the inaction was that it was so difficult to see. An eyewitness on the Headland told The Northern Echo: "It was very dark and there was a thick fog, which stood up before you like a hedge."

HARTLEPOOL DEFENDED

At 7.45am, HMS Doon, a destroyer on the sea near Hartlepool, fired one torpedo from three miles away at the three German warships. Realising it was out-gunned, it retreated, allowing the bombardment to begin.

There were two light cruisers in Hartlepool harbour. HMS Forward was not in steam and so could not respond. HMS Patrol ventured forward, was hit by an enemy shell which killed several sailors and ran aground. A submarine, HMS C9, came under attack and dived, which was probably a bit embarrassing.

The soldiers manning the batteries on the Heugh were heroic. They were members of the Durham Royal Garrison Artillery and two companies from the 18th Battalion, Durham Light Infantry – the "Durham Pals".

The first shell fired by the German flagship Seydlitz killed four of the Pals outright. The second shell landed in the same place, and killed four more who had gone to their stricken colleagues' aid. It also wiped out their radio so to communicate, they either had to use a megaphone or run amid the shellfire.

Still, the Lighthouse Battery fired 123 shells. It struck the battlecruiser Blucher so frequently that nine sailors were killed and it was effectively driven out of the bombardment.

THE DEAD

All of the 150 victims had sad stories, such as Miss Ada Crow, of 124 Falsgrave Road, Scarborough, who heard the roar of the guns, shouted to her parents as she skipped downstairs that the military were "only practising", opened her front door and was killed immediately. That evening, her fiancee, Sgt GR Sturdy, returned home from France on leave with the intention of surprising her and walking her up the aisle. He was said to be "greatly overcome".

The most famous of the victims are the soldiers – the first soldiers to be killed on British soil in the Great War.

For propaganda purposes, the War Office decided Pte Theophilis Jones, 29, was officially the first because of his story. At the start of the war, he had returned from his headteacher's post in Leicestershire to serve local children as assistant headteacher at St Aidan's School, West Hartlepool, and to join the Durham Pals. A prayer book that the children had given him was reputedly found in his pocket, with a piece of shrapnel lodged in it – only a callous enemy would kill such a decent man on his home soil.

But three other men died when the first shell landed on them beside the lighthouse: Pte Charles Clark of West Hartlepool, Pte Leslie Turner of Newcastle and L-Cpl Alix Liddle of Darlington.

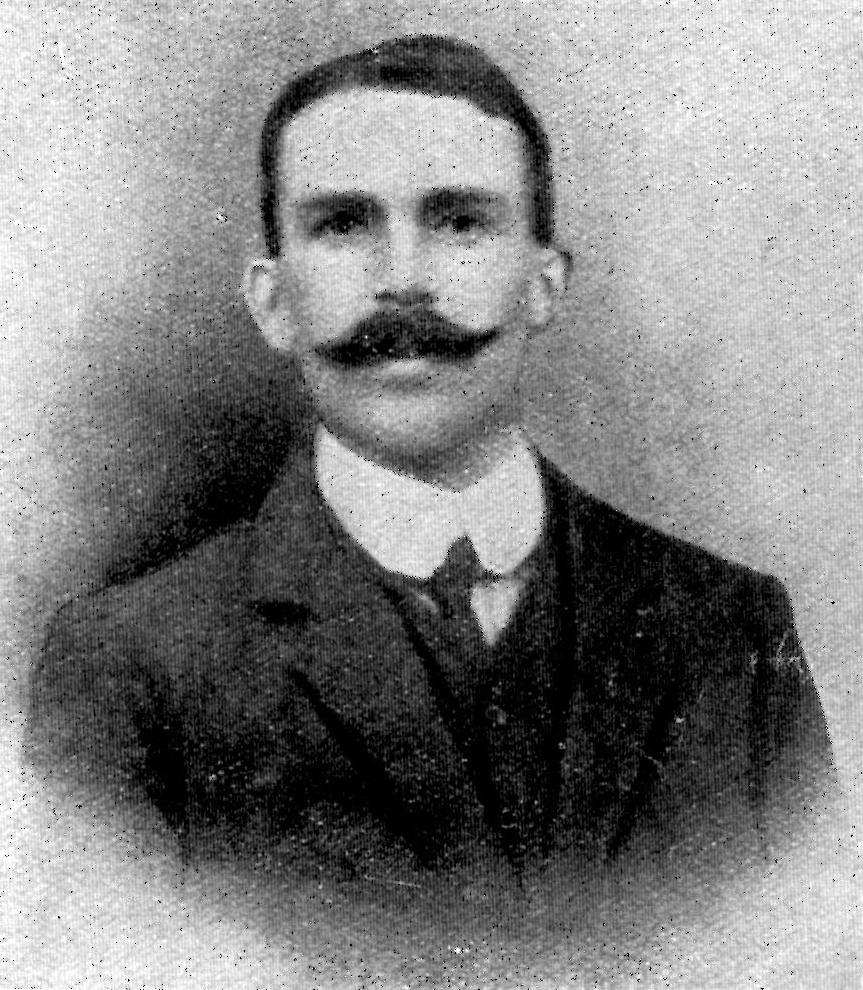

Memories told the story of Alix Liddle, a 25-year-old recently married colliery accountant, last December. It can be found on our North-East At War website, and because he was a bellringer at St Cuthbert's Church in Darlington, those bells will, muffled, ring out in his memory on Tuesday.

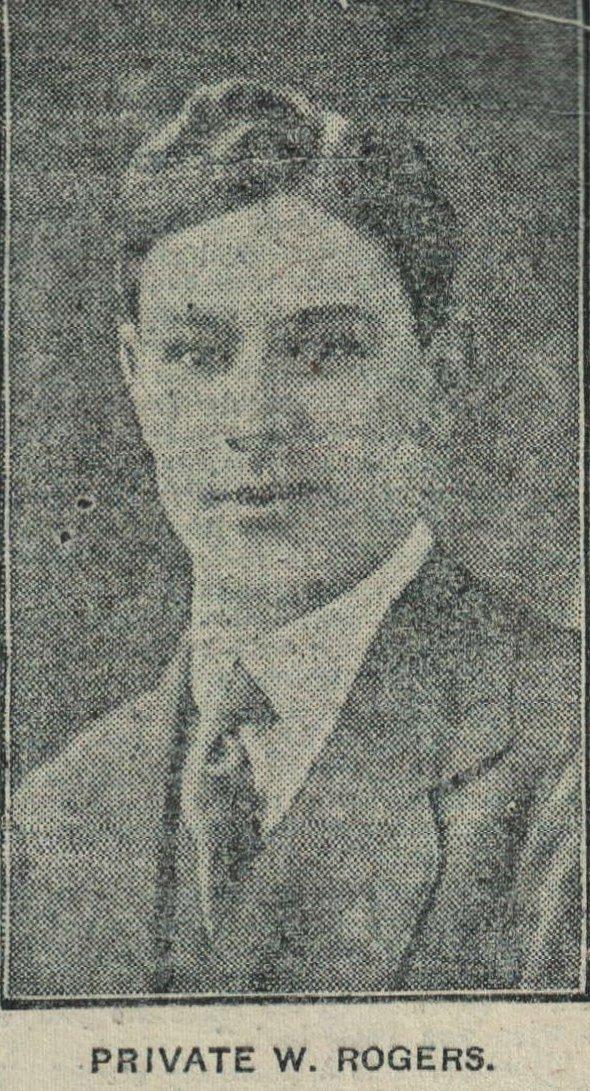

Another of the Durham Pals to die was Pte Walter Rogers, 25, of Bishop Auckland. "He was killed while in the act of covering up Cpl Liddle," said the Northern Despatch. "Pte Rogers received the full force of another splinter from a shell in the chest, but he lingered for three hours."

Both men's funerals in their hometowns were hugely attended. Memories visited Pte Rogers' headstone in Bishop Auckland Town Cemetery this week and despite the best efforts of the gale, it was clear someone had recently laid flowers – does he have any descendants?

THE AFTERMATH

There was understandable and widespread fear, if not panic, across the North-East, but the Government seized upon the bombardment for propaganda purposes.

Although Hartlepool bore the brunt, the Government regarded it as a distant Durham industrial town, whereas the plight of Scarborough – a genteel, fashionable resort – was more resonant, particularly as it was home to the youngest victim, John Ryalls. The 14-month-old was crying in the arms of his nanny, Bertha McEntyre, when his bedroom was struck and both were killed.

This led First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill to condemn "the baby-killers of Scarborough" and "Remember Scarborough" became the cry at the recruiting offices.

One poster screamed at men who were shying away from signing up: "Avenge Scarborough. Up and at 'em now. The wholesale murder of innocent women and children demands vengeance. Men of England, the innocent victims of German brutality call upon you to avenge them. Show German barbarians that Britain's shores cannot be bombarded with impunity. Duty calls you now. Go today to the nearest recruiting depot and offer your services for king and country."

It seems to have worked.

As The Northern Echo said in its editorial on the day after the outrage: "No, this is not war. It is the work of men whose lust for destruction seems only to be limited by fear of the consequences of being caught red-handed.

"But perhaps the most immediate effect upon this nation will be to stimulate a rush to the recruiting offices. "

PANEL

From Monday, our northeastatwar.co.uk website will be running a special feature on the 100th anniversary of the bombardment, including all the recent Memories articles about it.

Among the events taking place on Tuesday in Hartlepool is an outdoor service in Redheugh Gardens from 8am to 9am – the time of the attack. At midday, the Lord-Lieutenant of County Durham Sue Snowdon, will unveil a new memorial and pupils of Pte Jones' former school will read out the names of the 130 people who died in the town. At 6pm, the outdoor theatre production Homecoming will be performed for the last time in Headland Town Square. It was excellent when Memories saw it recently, so call 01429-890000 to get as free ticket.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here