A clear-out of an attic leads Echo Memories to Hurworth, and the region's role at the centre of the nation's bleaching industry

RITA CHAPMAN was tidying out her Darlington attic recently when a plastic bag of old grey-white linen sheets, untouched for 20 years, burst open and a note written by her late mother came fluttering out.

It said the sheets were not material for the jumble or the charity bag. Instead, her mother’s handwriting said they were a family heirloom, made in 1850 by someone called Coulson, who lived and worked in a passage in Hurworth. At the top of the passage, Rita’s great-grandmother once had a shop.

So Rita’s sheets can transport us back to the days when a couple of hundred people in Hurworth were employed in the linen trade and the lanes out of the village were crowded with men carrying packs of linen on their back, or with ponies laden with linen in their panniers, taking the fruits of the looms to the merchants in Darlington.

For some reason, the waters of the Tees and the Skerne in the Darlington area were noted for the excellence of their bleaching properties.

Items from as faraway as Scotland were brought to be bleached, and Aycliffe Village, northern Darlington and Neasham, as well as Hurworth, had their beginnings in bleaching.

Darlington also had well-organised merchants who began industrialising the linen industry. For example, there is a record dated 1777 showing that John Clement, of Darlington, was awaiting the arrival in Stockton of flax worth £500 from St Petersburg in Russia – that would be worth more than £70,000 today, so his clearly wasn’t a one-man operation.

Once in Darlington, the long fibres from the flax plants’ stems would have been heckled out and spun into yarn, which would then have been delivered to the linen weavers to turn into material.

In Hurworth 200 years ago, the linen workers lived at the east end of the village in an area known as the “old barracks”.

This does not suggest a military usage, but instead is a more literal translation of the French word “baraque”, which means a temporary hut or a shed. In these huts and sheds, many of which were dug into the banks of the River Tees, worked the weavers.

In the early 1830s, 120 handloom weavers – all male – were at work in these dark, dank subterranean rooms.

“The business was prosperous,” wrote Dr Thomas Dixon Walker, the village GP. “By only working five days in the week, and spending the other two in dissipation, an able-bodied man could earn from 25 to 28 shillings per week.”

And there probably was plenty of dissipation among the east end linen-workers in the Otter and Fish, and the Emerson Arms, and there is still evidence of how people tried to turn the tide of drunkenness.

The village hall was built in 1864 as a Temperance Hall; opposite it, in what today is a dentist’s surgery, was a cocoa palace opened in 1878 to lure men away from the pubs; and in the nearby churchyard, the largest memorial is dedicated to the Hurworth Temperance Society, which had taken over from the Hurworth Teetotal and Prohibition Society in pushing the cause of sobriety.

Things, though, began to change in the late 1830s, when at the west end of the village, the first stretch of the railway main line between Darlington and York was begun. Hundreds of men were required to dig out the deep cuttings on either side of the river, and many of the weavers – who must have sensed that the railway would bring greater mechanisation which would render them redundant – were tempted to join the outdoor life.

Dr Dixon Walker wrote: “The consequence of men leaving a sedentary vocation for an active employment was followed by remarkable results. Those who escaped injury, earning good wages, and consequently living upon the fat of the land from being poor and lean, unwashed artificers swelled out into strong, muscular, powerful and able-bodied men, so that in a few weeks I scarcely recognised them.”

The men of Hurworth still had money to spend in dissipation, but they no longer earned it as weavers, and the last of the handlooms at the east end of the village fell silent in the 1850s.

Therefore, Rita’s sheets must be among the last that Hurworth ever produced.

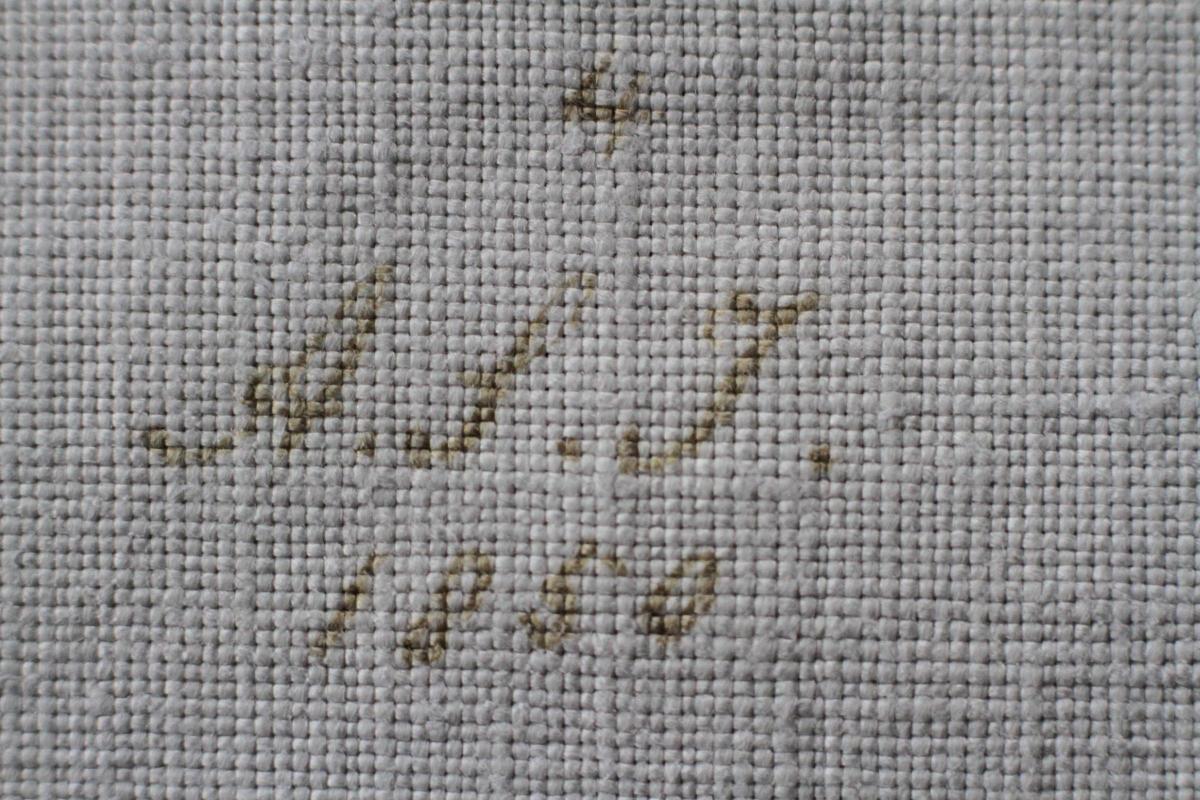

To prove their authenticity, in faded black ink in a fancy hand, someone has written “AJJ 1850”.

We don’t know who the lucky first owner of the sheets was, but the family surname back then was Jopling.

Perhaps the sheets were acquired by Rita’s great-grandmother, Annie Jopling, born in 1861, who ran “a variegated shop”, selling confectionery beside the Temperance Hall and next to where Mr Coulson had his workshop.

They must have been handed down to her daughter, Jessie, born in 1891, who married Henry Manning in 1908. Henry’s family ran a farm at Skipbridge on the edge of Hurworth, and he worked first as a cartman, and then as a railway porter at Moulton station, less than ten miles away.

Henry joined the Royal Artillery during the First World War, and served in Gallipoli, Salonika and Turkey – and came home.

During the Second World War, when rationing prevented families from getting many luxuries, Jessie had one of the old sheets dyed green so it could be used as a bedspread.

When she died in 1972, the sheets passed to her daughter, Grace, who died in 1992, so they passed on to her daughter, Rita, who kept them safely in the attic.

“We’ve had things in the loft for ages and ages, so we were starting to get rid of things,” said Rita. “I had forgotten they were there. I was very surprised when the bag opened and her note dropped out.”

The note reprieved the sheets from the charity bag – but now Rita has got to find somewhere else to keep them.

Chris Lloyd’s book, The Road to Rockliffe, features several chapters on this end of Hurworth.

It is available for £12.50 from The Northern Echo’s office in Priestgate, Darlington, Waterstone’s in Darlington’s Cornmill Centre, and Croft News in Hurworth Place.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here