THIS year marks the 150th anniversary of the death of one of the greatest engineers of the Victorian era and next weekend, to commemorate the anniversary, one of the greatest mysteries of Darlington’s South Park will be explained.

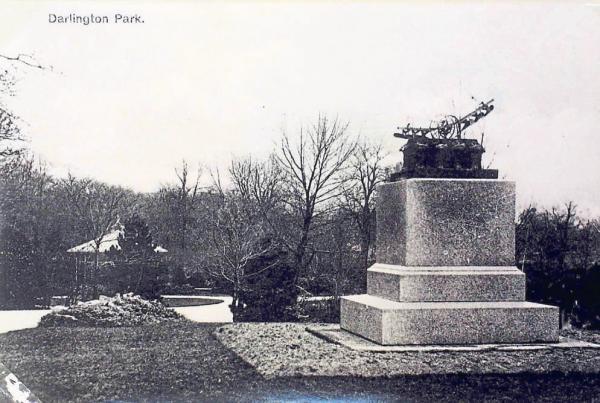

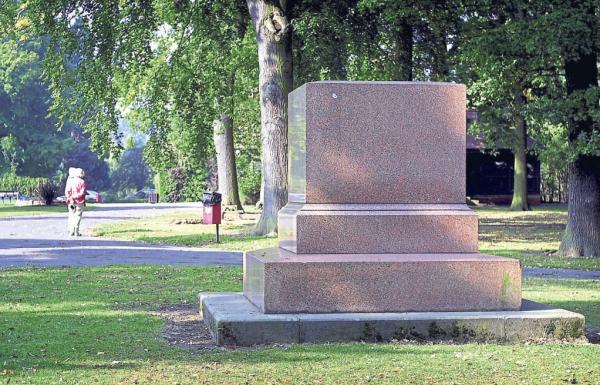

Beneath the trees, overlooking the park lake, stands an imposing block of red granite with just the words “John Fowler CE 1856” carved into it. Until the 1970s, a bronze model of a steam plough sat on top of the granite block, giving a clue as to who Mr Fowler was, but since the scrap metal men stole it away in the middle of the night, there has been nothing.

On Saturday, though, at 2pm, the Friends of South Park and the Steam Plough Club combine to unveil a new information board which will explain all about Mr Fowler. A model of the steam plough which he invented, and which acquired for him “a world-wide celebrity” in 1856, will also be on display.

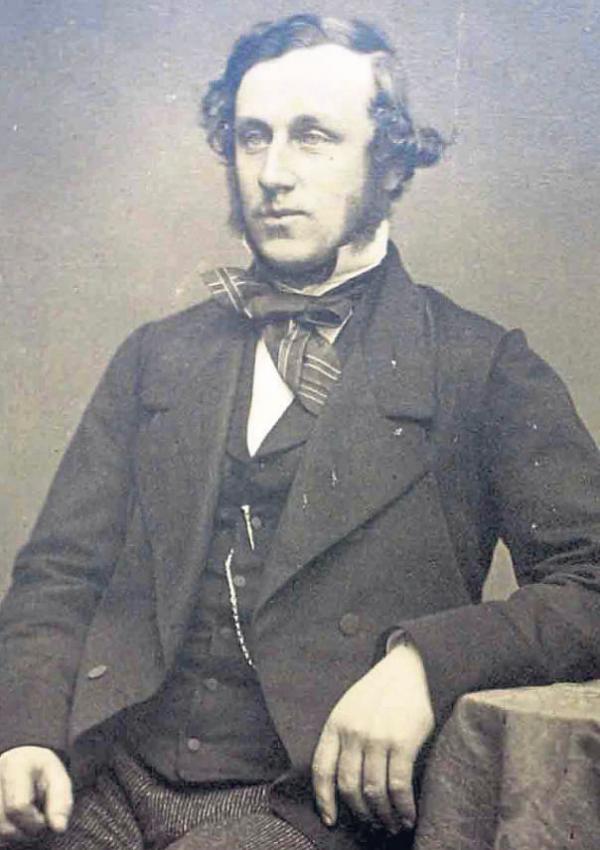

Fowler was a young Quaker from Wiltshire who came to the North- East in 1847 to learn to be an engineer with the Middlesbrough firm of Gilkes, Wilson, Hopkins and Company. Two years later, the company sent him to Ireland where he was so shocked by the aftermath of the potato famine that he jacked in his job and dedicated his engineering skills to alleviating the distress of the Irish poor.

In 1850 in Bristol, he set up a firm with Albert Fry – of the Quaker family of chocolatiers – to build horse-drawn drainage ploughs.

These wowed the crowds at the 1851 Great Exhibition, and the Irish peasants used them to drain their peat bogs.

To make the plough even more efficient, Fowler wanted it driven by steampower. He asked Darlington’s Joseph Pease for advice. Mr Pease – whose statue stands on High Row – put him in touch with Robert Stephenson, who allowed him to use his factory on the banks of the Tyne to create a steamdriven device which would compete for a £500 prize being offered by the Royal Agricultural Society of England to the first person to invent a machine which could be mathematically proven to plough a field more efficiently than horsepower.

Fowler placed his steam engines on either side of a field and joined them with a cable. To the cable he attached a plough. The engines pulled the plough across the field, flipped it over and then sent back to the other side of the field. In 1856, Fowler announced that by this mechanical method, he was ploughing an acre an hour – but the Royal Society computed that horses, although slower, were still 2½d-anacre cheaper.

Perhaps to compensate, Fowler returned to Darlington and asked Mr Pease for the hand of his daughter, Elizabeth, and they were married in the Friends Meeting House in Skinnergate on July 30, 1857.

Next year, after fine tuning his plough, Fowler satisfied the Royal Society’s mathematicians, won the enormous first price, and his device – and his fame – went global. Egypt and Hungary were two early adopters of the Fowler steam plough.

The inventor used his prize to set himself up in business in Leeds – to this day at steam fairs you can spot Fowler traction engines by the distinctive roundel on their fronts. He employed 400 men and 32 patents to his name – everything from his ploughing equipment to a device for laying electric telegraph cables.

But the pressure of running a steam factory grew until he was fit to burst. His doctor diagnosed stress and prescribed vigorous outdoor activity. Fowler started energetically riding the 12 miles into work every day.

Still the symptoms persisted. The doctor prescribed even more vigorous activity, so Fowler started hunting with hounds. Out in the field in November 1864, he tumbled from his horse, broke his arm, tetanus set in and he died on December 3, 1864. He was just 38, and left Elizabeth with five young children.

He was buried in the Skinnergate graveyard, and the Peases were so upset that they commissioned the imposing granite memorial. They placed it in the grounds of the Pierremont mansion, off Woodland Road, which belonged to Elizabeth’s uncle, Henry Pease. In the 1870s, Henry’s lavish pleasure gardens were open to the public and drew thousands of visitors from across the region.

But when Henry died in 1881, the gardens closed, and the granite block, with plough on top, was taken to South Park.

There it remains to this day. Even though it is without its model plough, at least from next weekend there will be a board explaining who John Fowler CE was. You are more than welcome to attend the unveiling.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here