THANKS to the gentle BBC comedy drama Detectorists about metal detecting enthusiasts, the much-maligned Triumph TR7 sports car is cool – possibly for the first time in automotive history.

Unfortunately the bright yellow TR driven by actor Toby Jones in the series isn’t supposed to be cool. Diana Rigg’s summation of the car probably sums most people’s view of the controversial wedge when it was launched in 1975 – “What a funny looking little car.”

Although the TR7 was the final nail in the coffin of what had once been Europe’s best-selling sports car range – and the nadir of British Leyland’s poor quality control – it actually succeeded in spite of itself.

By the time production finished in 1982 it was the best-selling Triumph sportster of all-time.

The TR was the ultimate car designed by committee. It was the product of an internal power struggle between MG and Triumph, designed according what car salesmen in America thought their customers wanted and re-designed when BL chiefs thought US safety legislation would make drop-tops a thing of the past.

Short cuts taken to get the TR7 to market would saddle the car with a reputation for unreliability which was thoroughly well-deserved and industrial unrest would put paid to BL’s plans for it to sire an entire TR7 family.

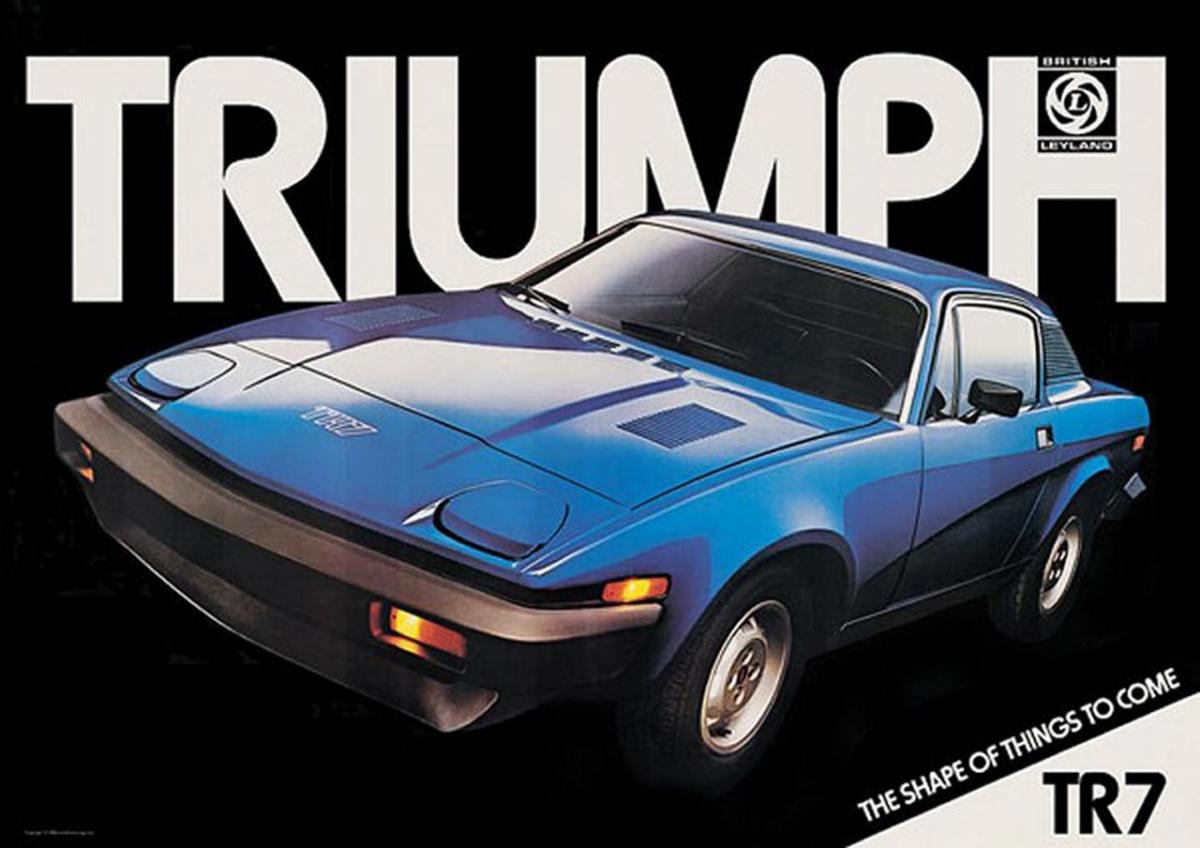

Looked at today it’s hard to believe the impact Harris Mann’s dramatic wedge shape had when the world got its first look at the TR7.

There’s a (possibly apocryphal) story about the legendary designer Giorgetto Giugiaro who saw the TR at the 1975 Geneva Motor Show. He looked at one side, nodded his head and walked around to the other before guffawing: “Oh my God! They’ve done it to the other side too.”

Beneath the outlandish looks the TR was entirely conventional.

Back in 1970, when BL was looking to replace the MGB and the TR6, the designers at MG came up with an ambitious (and bonkers) mid-engined creation with distinct echoes of the Chevrolet Corvette C2 (more commonly known as the Sting Ray).

The boys at Triumph, mindful that BL’s coffers were almost empty, fielded a front-engine/rear wheel drive design, code-named Bullet, that could be built quickly and cheaply. Naturally, the Triumph team got the go-ahead.

Head man Donald Stokes said the new car had to go on sale in 1975. The clock was ticking.

So Triumph dipped into the corporate parts bin. The engine was a development of the slant four engine co-developed with Saab and already used in the Dolomite saloon. The four-speed gearbox was a Morris Marina hand-me-down and even the door handles were nicked from an Austin Allegro.

The standard TR7 was disappointingly staid but there were plans to use the 16-valve engine from the Dolly Sprint, the Triumph in-line six and (when this proved impossible) the venerable Rover V8 which was already used in the Range Rover and the Rover P6.

Harris Mann’s decision to go with a dramatic wedge shape can be forgiven because so many other cars went the same way in the early 1970s, but BL’s insistence on those horrendous black plastic impact-absorbing bumpers made the car look dumpy, not dramatic. BL urged Triumph to adopt the bumpers because it feared new US road safety legislation which also looked set to outlaw convertibles. Anti-pollution laws also strangled the performance. In California, the TR7 had a mere 76bhp (less than a modern Fiat 500).

As well as the 16-valve and the V8 models, Triumph also developed a 2+2 version as a potential rival for the Reliant Scimitar/Ford Capri. Called the Lynx a couple of development models were built and BL’s new boss Michael Edwardes took one as his company car for a time.

What a shame, then, that Edwardes would be the man to kill the Lynx as part of an on-going battle with militant unions at the Speke factory, in Liverpool, where the TR line was built. After years of industrial strife Edwardes shuttered the factory – moving the TR7 to the decidedly less bolshie Canley plant, near Coventry, but not its more practical cousin, the Lynx.

A convertible version finally arrived in 1979. Cutting off the roof improved the TR’s looks no end and a strengthened floorpan ensured the car didn’t feel much different from its hard-top cousin.

In May 1981, BL management said the TR7 was under threat – and would only survive if demand picked up.

For a time the company toyed with the idea of rebadging a modestly facelifted TR as an MG to replace the old MGB. Pictures exist of the MG TR – and several were shipped to the US for dealer evaluation – but, in the end, this proved too expensive. Production of the Triumph TR7 came to an end in October 1981 and it would be more than a decade before BL once again built a ‘proper’ sports car.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel