In the first of a six-part reprise of 46 years in the inky trade, Mike Amos – who is retiring on Friday – recalls early days with strings attached.

THE workhouse – Dickens’ workhouse, the workhouse of Bumble Beedle and of Artful Dodger – could hardly have been more greatly stoned into silence than was the Priestgate canteen after my first three hours in journalism.

I was 18, had three decent A-levels, but no desire to go to university, probably been the principal contributor to the Bishop Auckland Grammar School magazine.

Even by the immature standards of 1965, the magazine was awful, precious in a Woolworth’s jewellery sense. Mine were the worst bits of all.

It was what now would be called relevant experience, and it was all there was.

I’d been appointed to the Northern Despatch, the evening paper for Darlington and south Durham, always a bit of a poor relation to The Northern Echo though successive editors, inspired and articulate, strove to make it otherwise.

The first job of all, that green, green morning of August 30, 1965, was to compile for that evening’s paper the “Fifty and Fives” list of cricketers who’d hit a half-century or taken five wickets the previous weekend.

Ken Thwaites – familiar North Yorkshire cricketer, footballer, greyhound trainer, racing man, headmaster and church organist – recalls being among those very first names.

So, for that matter, was the evergreen Jack Watson, now 90.

The task inelegantly completed, it was a relief to get out of the newsroom and into the canteen. Unofficially it was known as Winnie’s Bistro, after the friendly manageress, though few other bistros may have had tea spoons tied to the counter.

Lunch, inevitably, was meat and two veg. The cabbage couldn’t have been greener, nor more innocent, than I was. Amid it, cooked in and cholesterol-free, I found a piece of string.

How long is a piece of string? Lest there be early accusations of journalistic licence, let’s say about six inches, served with mashed potato and a rather lachrymose gravy.

What to do? Should I complain and risk at once being identified as a trouble maker or say nowt and feel as guilty as a Monday morning court list?

Stick or Twist, I complained.

The news editor’s reaction may most kindly be described as unsympathetic.

For “You want more?” read “Shut up or everyone will want a bit”.

That’s the polite version, anyway.

You could have heard a tea spoon drop, or at least you could had it not been fastened down. Probably they recalled the phrase about rope and hanging.

It would neatly wrap up the story to record that, given the Elba, I was banished to Bishop Auckland after the first week. In truth, I was due to work in Bishop office, anyway.

Even without the unexpected, but wholly enlivening, appearance of the Honourable Diana, they were to prove the most memorable three-and-a-half years of my life.

THE first weekly wage was £9 1s 6d, rising on the 19th birthday the following month to £10 2s, the cheque cashed every Thursday at the Midland Bank down the street.

The Bishop office was above a money lender’s though, to be fair, the only time we saw him was when periodically he stomped up the stairs to complain about us playing football in the corridor. We played football quite a lot, three-card brag even more.

There were six of us, three on the Despatch and three on the Echo, another two or three squeezed into the shoebox Auckland Chronicle office next door.

Between the six was one elderly black telephone (Bishop Auckland 2232), two or three vaguely serviceable typewriters and maybe four or five chairs, several held together with the sort of heavy-duty string that seemed inadvertently to have strayed into the cabbage.

If everyone were in at once, the most recent arrivals would have to squat atop a pile of old newspapers, while waiting his turn on a typewriter.

The greatest irritation of all, however, was carbon paper, its demise the chiefest blessing of the technological revolution. The newspaper required four copies of everything and every one of them double-spaced. If not exactly blood brothers above Mr Bell the money lender, we became a sort of Black Hand Gang, nonetheless.

HARRY STOTT was chief reporter; we called him Harry Stottle. He was a truly delightful man of 60 or so, genial and generous, but had long since surrendered his journalistic wits. Harry liked a drink.

From the first day of the second week, it became obvious that the Bishop Auckland office of the Northern Despatch was to be a case of sink or swim. Dog paddle, maybe, but it suited me fine.

A lot of the work was magistrates’ court reporting, the juniors sent down the road to Bishop Auckland while the older hands charged expenses – in triplicate – to travel in the same car to courts at Spennymoor, Stanhope and Wolsingham. Though the court list was usually light, they rarely returned before 3pm.

In the evenings, no overtime, there was always a heavy diary of council committee meetings – Bishop, Crook and Willington, Shildon, Spennymoor, even Tow Law Urban District Council, where a good spat between Jimmy Jones and Janet Gill was all but guaranteed.

They gave me Bishop Auckland, meetings frequently running until after 9pm and all stories to be written and delivered that night to Bishop Auckland railway station, for early morning carriage to Darlington.

The yellow and red envelopes were marked “Important: News Intelligence”.

Sometimes it was turned midnight before they reached Bishop station, and still a bike ride home to Shildon. At that hour, it has to be said, some of it didn’t seem very intelligent at all.

BISHOP Auckland UDC was for the most part ruled, like the town, by Alderman JRS Middlewood, an opinionated, autocratic and overweight former railwayman who also wielded much power at County Hall.

Bob Middlewood brooked little argument, on one occasion summoning the police to eject from the council chamber Jimmy Mudd, an elderly, urbane and altogether appealing independent from Escomb.

Then there was George Steadman, am excitable Labour maverick who, after a meeting, pulled a gun in the alley across from the town hall on someone who’d crossed him during debate.

It proved just to be a starting pistol, but still made a great story. I never have subscribed to the journalistic theory that council meetings were dull.

MOSTLY the young reporters were left to their own devices, self-starting pistols.

The newsdesk seldom bothered us out there; Harry was just grateful that someone was doing the work.

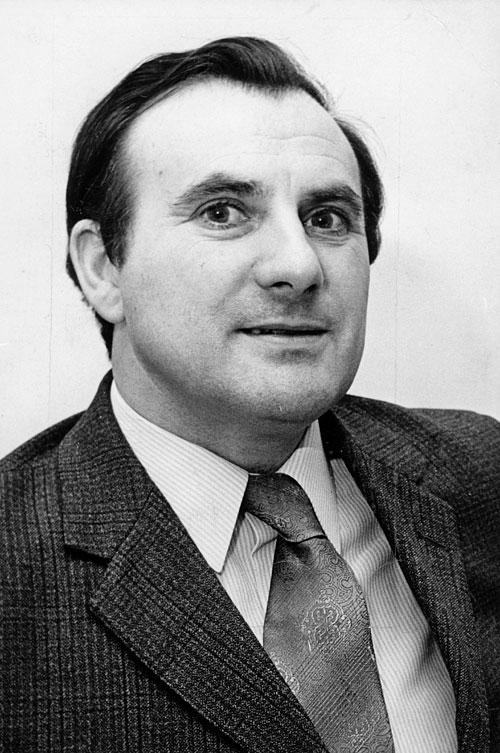

On one unforgettable occasion, however, Arnold Hadwin – the editor – rang home at 2am. There was to be no more sleep that night. Arnold was the man who’d given me the job, swore subsequently that senior colleagues had urged upon him the error of his ways.

He was a Spennymoor lad, had himself been a junior reporter in Bishop Auckland, did National Service with the Royal Marines, qualified for Ruskin College, Oxford, and, after a highly-distinguished journalistic career was appointed OBE.

Someone, at any rate, had told him that the river at Page Bank, just outside Spennymoor, had burst its banks, overwhelming the entire village. It was such a big story, the firm paid for a taxi.

The scene was unbelievable, the whole village – known locally, not unaffectionately, as Egg Cup Alley – subsequently demolished. Every resident and every rescuer had a story, most of which we probably missed.

In the inky trade they call the main front page story the splash. The Great Flood of Page Bank was to overflow for many years to come.

BILL OLIVER was one of the reasons why working in Bishop Auckland was so enjoyable.

He was the district photographer, covered all the titles but – armed with the sort of heavy duty camera with which Neanderthal man might have clubbed a brontosaurus – was pretty much a law unto himself.

Bill it was who’d pre-enact scenes from Bishop Auckland football matches in order to get an “action”

picture into the Pink, who’d smoke cutting-edge Capstan, but only rarely drink rum and pep, who waited for hours outside a building in Bishop Auckland because a gale was blowing, he thought the roof was going to come off and that it would make a great picture. It did, on both counts.

We’d usually meet about 9 30am for a Bovril and a dry cream cracker in Rossi’s café, conclude that the day’s news prospects seemed arid, fall back upon Bill’s endless list of stories, just one careful owner.

The best story of all, however, concerned one of his periodic visits to the Bowes Museum in Barnard Castle, usually to record one of the Queen Mother’s visits.

Bill was running late, probably been sent to Ferryhill and Frosterley “on the way”, smiled his Steradent smile, doffed his elderly tweed hat and asked Her Majesty if she’d mind doing it all again.

The version that he said “Sorry, luv” may be supposed apocryphal.

The Queen Mother paused briefly before remembering him. “Why certainly, Mr Oliver,” she said, picked up both ends of the snipped ribbon in the same hand and turned, beaming, towards him.

As usual, Bill got his pic.

AFTER 18 months it finally proved too much for dear old Harry Stottle. They made me Bishop Auckland chief reporter, a boss’ job at last.

In 1969, I became northern political correspondent – or some such spurious title – back in Darlington. Mostly it involved the Borough Council, occasionally a day out to Westminster.

Still politicians were being offered safe seats in the grounds of lengthy party or union service, not always because of cosmic intelligence. A favourite Strangers’ Bar story was of the Tyneside MP who, after two silent years, was prevailed upon to make his maiden Commons speech when a major pit closure was announced on his patch.

“This here pit closure,” he announced, “will mean the crippilisation of my constituency.”

The following morning, the girl from Hansard knocked timidly on his door, confessed that she’d checked all the dictionaries and couldn’t find “crippilisation” anywhere, asked if that were really what he’d said.

He was a kindly old cove. “Hinny,”

he said, “if thoo dissent understand lang words, just put it in invertebrated commas.”

Back in Priestgate the canteen, like another of Charles Dickens’ celebrated workhouses, remained in full vigour. The wage having risen to £14 10s, however, it seemed more prudent to stick to double pie and pies in the Red Lion.

Eye witness accounts

EVERYONE asks. How did you get into journalism? Back in 1965 it wasn’t especially easy, these days it rather resembles the camel and the eye of a needle (which, as everyone knows, is Matthew 19:24.) The usual answer, only semi-jocularly is that it was the only job that didn’t require a medical.

For reasons of incorrigible eyesight, the test would certainly have been failed.

Barely able to read the lesson at my thanksgiving service two weeks ago, I recalled the eye test at which the optician had announced: “Oh, so you’re colour blind, as well.”

“As well as what, exactly?” I replied.

One of those at the service recalled that the tale had previously been told in print. “You described it as a bolt out of the green,” he said.

There are very much worse things than having enfeebled eyesight. Had I been able to read the blackboard, goodness knows, I might have become an accountant instead of failing O-level maths four times.

Each time I got a nine, the lowest grade. Four nines, as everyone knows, is 32.

I remain the only sports columnist who had to buy a Pink to find out the score, the only cricket fan who has never seen the ball because a cricket ball is red and a cricket pitch is green.

Every cloud has a silver – or whatever shade it is – lining, though. Just think of all the money made by Arriva and its predecessors – I really must get a bus pass – and by the rail companies during these 46 years endlessly traversing the region.

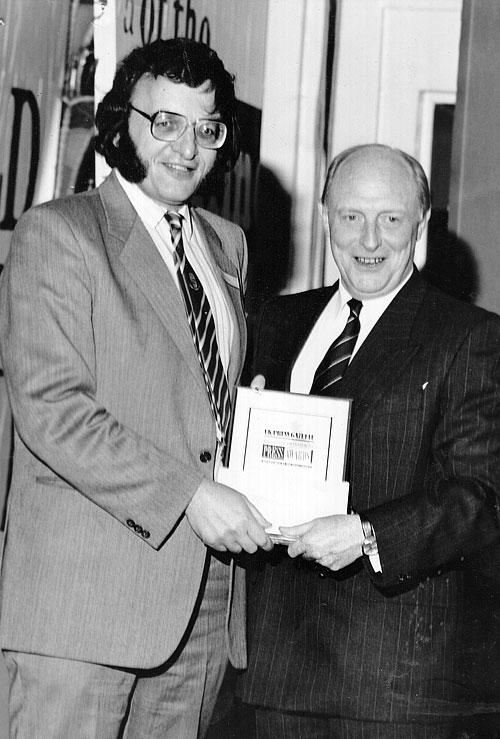

Perhaps the most memorable case of grand myopia, however, was at one of the national Press award ceremonies, held in the vast ballroom of a swanky London hotel. The awards were to be presented by Neil Kinnock, then leader of the Labour party.

Those considered no-hopers were coralled in some out-of-sight corner at the back. It was thus something of a surprise to be proclaimed UK Regional Sports Journalist of the Year and a still-greater surprise for the poor commissionaire with whom I ended up shaking hands.

Kinnock was 20 yards away, laughing like a Max Boyce LP.

There have been many other awards, every one a real thrill. The really good news is that, even in semi-retirement, I hope to see my way to quite a few columns yet.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here