A North-East woman who helped expose one of the NHS’s worst scandals is not giving up after nearly two decades of campaigning.

Health editor Barry Nelson met Carol Grayson.

CAROL GRAYSON’S flat is positively bursting at the seams with souvenirs from far-flung corners of the world. Russian dolls sit next to effigies of Indian deities while Indonesian puppets jostle for space next to Mexican momentoes.

But pride of place in her Newcastle living room goes to the two awards she received for her remarkable efforts to highlight the plight of the nearly 5,000 British haemophiliacs, who for years were routinely given blood products donated by skidrow American prisoners who were often suffering from Hepatitis C and HIV.

The tragic exposure of so many vulnerable patients to these potentially deadly diseases has so far cost about 2,700 lives.

Another 2,000 – many of them ill with HIV and Hepatitis C – struggle on in the hope that they will one day receive adequate compensation for the suffering they have gone through.

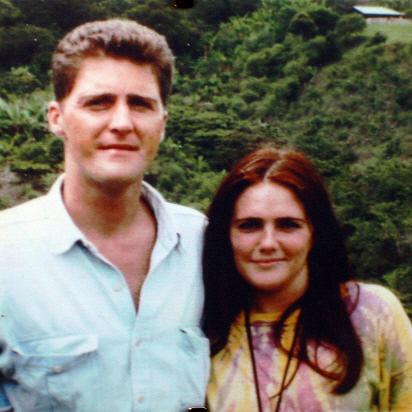

Among the victims was Carol’s husband, Peter Longstaff, who spent years campaigning with her to get justice for the victims of contaminated blood until he succumbed to the effects of Hepatitis C in April 2005.

Carol, 50, first knew Peter in the pubs of Hartlepool, the town where they both grew up.

In the early Nineties, when she moved to Newcastle, they bumped into each other again.

She still remembers how shocked she was at his appearance.

“Peter was very ill, underweight and very depressed.

By then, he knew he was HIV positive, but didn’t know he also had Hepatitis C,” she recalls.

Peter had lost his brother, Stephen, a fellow haemophiliac who succumbed to Aids acquired through contaminated blood, as well as his father, who died of a heart attack while campaigning against the stigma that surrounded HIV/Aids in the early days.

“Peter had just given up on life but I realised it was actually more psychological,” says Carol.

Three months later, the couple were on a plane to Mexico and a reinvigorated Peter was about to go on an epic backpacking journey that would take them from Mexico to Brazil and then from Indonesia to China, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Vietnam over the next few years.

“He had just given up on life.

He had lost his father, lost his brother and his marriage had broken up. So I fed him up, got him on t h e lowest possible dose of painkillers and persuaded him to fulfil his dream of travel.”

During their epic journey across two continents, Peter was sustained by packs of dried plasma sent out to various British embassies by his NHS hospital back home.

“It came as dried white powder which caused a few problems with customs until we showed them the paperwork,” says Carol.

The powder was mixed with sterile water and then injected by Peter to help his blood clot.

“Sometimes, he would have horrendous bleeds and we would have to rest. By the time we got back home he must have been one of the most well-travelled haemophiliacs in the world.”

When they got back from globetrotting both committed themselves to exposing the full horror of the contaminated blood scandal and supporting other victims via an unofficial helpline.

They both pretended to be medical students and spent day after day studying documents in Newcastle Medical School’s library.

As a qualified psychiatric nurse, Carol was able to understand most of the literature.

“Using batch numbers, we were able to trace it right back and we found that one of Peter’s donors was an HIV positive prisoner.”

They were horrified to learn that some prisoners in Arkansas and Louisiana state penitentiaries were allowed to give plasma even when they were yellow with Hepatitis C.

“One prisoner had the job of resharpening the needles used by donors with sandpaper,” recalls Carol, who helped the BBC Newsnight team make programmes about the blood scandal.

Heat treatment of plasma in the mid-Eighties got rid of the viruses, but it was too late for thousands of haemophiliacs around the world.

It was also too late for Peter, who died on April 16, 2005, aged 47.

His name appears on the citation of an award presented to Carol in the US last year and it is in Peter’s memory that Carol has dedicated the best part of two decades to righting a terrible wrong.

THE saga – which dates back to the Seventies – was recently described by the independent Archer inquiry as “the worst treatment disaster in the history of the NHS”.

The authorities in the UK insist no one was to blame, but campaigners like Carol say there is ample evidence which suggests that doctors knew about the threat of contamination long before it became public.

Despite the decision of the Irish Government to generously compensate its citizens who were affected by the scandal, the UK Government recently refused to make higher compensation payments to victims.

Currently, those with HIV receive £12,800 a year with separate payments for those with Hepatitis C.

In a House of Commons debate earlier this month, Public Health Minister Anne Milton ruled out a suggestion by the Archer Inquiry in 2007 that UK payments should match those made in the Irish Republic, arguing that the state of the public finances had to be taken into consideration.

Carol, whose research formed the basis for the inquiry’s recommendation that the UK should adopt the Irish approach, is determined to carry on with her campaigning until higher levels of compensation are paid.

On April 16, five years to the day after Peter died, a judicial review brought by a composer who contracted HIV and Hepatitis C through an NHS blood transfusion won a High Court challenge over compensation levels.

Mr Justice Holman ruled that the way the UK government had reached its decision on the scale of compensation to be paid to victims was flawed. However, this failed to impress the Government, and Julie’s campaign continues.

“I am now looking at whether there may be scope for more legal action,” she says.

“The frustration is that people can’t get closure.

A lot of the widows are suffering depression and find it difficult to move on. More than five years have passed since Peter died and I still can’t get on with my life. I have got to see this to its conclusion.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here