Fears over immigration have been stoked by EU referendum rhetoric and there is a undercurrent of hostility towards people wanting to start a new life in the UK. Alexa Copeland finds out there are lessons to learn from one Middlesbrough family that didn’t discriminate

IMMIGRATION, Brexit and the refugee crisis have barely been out of the news over the last year.

In the seemingly endless run-up to the EU referendum and the months following, a section of vociferous politicians and media outlets have blamed immigrants for many social ills; from grooming our children to over-burdening stretched public services, ‘immigrant’ has become a byword for ‘problem’. But it wasn’t always so.

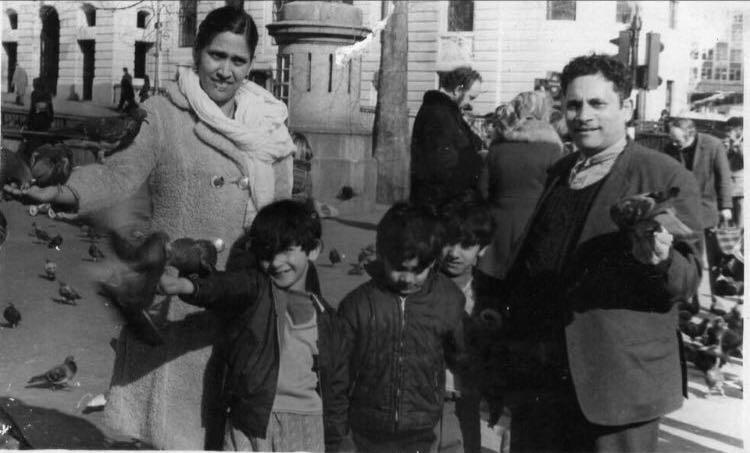

The Afzals on a trip to London; Iqbal and Muhammed with sons Asif, Saghir and Rasub

After the Second World War this country was literally crying out for healthy young people to come and help rebuild a battered Britain. And come and help they did. Without wanting to sugar-coat race-related problems that undoubtedly arose, the immigrants were cautiously welcomed into the communities that they grew to call home.

Iqbal Afzal was one such immigrant who came to Middlesbrough in the 1950s to settle with her husband Muhammed. The pair moved from Azad Kashmir into Monkland Street and went on to spend the rest of their lives in Middlesbrough.

Their home became seen as an unofficial community centre, welcoming people of all nationalities and faiths and helping them find their feet in a country foreign to them.

When Iqbal died aged 78 last month, around 2,000 people attended her funeral – a visible testament to the legacy she left on Teesside and beyond. And hers is a legacy we would do well to reflect on in these times of fear and hostility towards foreigners.

Rasub Afzal

“When she came here she couldn’t speak a word of English," Iqbal’s son Rasub Afzal explains.

"She came out of her house and there was a nice lady next door, and my mum smiled at her and she smiled back. And from that, that lady was kind enough to teach my mum words. She was a Boro lady and they became very close, and those words slowly became sentences; life becomes much easier when you can speak the language.”

Under the gentle tuition of her neighbour, Iqbal’s confidence grew with her ability to communicate and the couple soon became aware that there were others in similar need.

“A lot of these young people that came here didn’t have anywhere to stay,” says Rasub.

“They didn’t know the language, and most people who came to Middlesbrough ended up living in our house for a time. I remember my dad saying ‘I don’t know how many nationalities have passed through here’. So it didn’t matter where you were from; whether you were Italian, Greek, from the West Indies, if you were Sikh. It didn’t matter who you were, they stayed at my dad’s home and then they found work. There wasn’t an ounce of discrimination in my parents.”

The Afzal’s kindness helped scores of immigrants settle in Middlesbrough and go on to make a positive contribution to society.

Rasub describes how when his own daughters were young they were served by an elderly Italian ice-cream man who said he was one of the many who received help from the Afzals upon arriving in England decades earlier. And when Rasub’s father Muhammed was in hospital in 1982, before his death in 1984, he was on the same ward as a Greek man of similar age who it turned out he had welcomed into his home as a young man looking for work and a place to stay.

Rasub’s parents taught him to see everybody as equal, but he does see the difference in today’s reaction to immigrants and has some sympathy with communities who feel they are not benefiting from the new arrivals.

He believes it is important that those who come here integrate fully and treat England as their home instead of seeing it as ‘someone else’s home so they can do what they like’.

Yet although the broader social and economic circumstances may be different to when the Afzals arrived here in the mid-1950s, there are surely lessons to be learnt from their welcoming attitude and the way they were in turn welcomed into Middlesbrough.

Rasub says he felt "incredibly proud" when those 2,000-plus people came from all over the country to attend his mother’s funeral on October 8.

It was a tangible affirmation of the positive impact that her attitude had on so many people. And whilst immigration is currently bringing tension and problems in certain communities, the Afzals’ exceptional generosity to those in need should give us all food for thought.

For himself, Rasub tries to live by this advice left by his late mother and is now helping others in his role as a foster parent: "My mum told me, look son, I want you to be good people, if you can help people, help people. It doesn’t matter what colour they are or what faith they are, it is irrelevant. They are a human being.”

By Rasub's own admission, Iqbal was academically an "uneducated woman", but one might say that her conduct could teach our more hateful immigration commentators a thing or two about humanity.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel