For Second World War veteran John Twigger, 91, the Normandy landings in June 1944 and the subsequent restorations of France and Belgium bring back bitter sweet memories.

As a sergeant in the Royal Air Force Police he witnessed the death and destruction that accompanied the Allies’ invasion of France and the traumatising impact it had on those who survived.

At just 21-years-old, he drove an ambulance transporting injured men to hospital. He also ran a makeshift prison, where the majority of inmates were Allied soldiers unable to cope with the atrocities of war.

“It was very difficult,” says Mr Twigger, of Newton Aycliffe, County Durham. “Not everyone can handle war.

“These were ill men. We didn’t just say ‘you are under arrest.’ We would say ‘come on let’s find you somewhere to sleep.’ They were then sent home. There were hundreds like that.”

Yet, it was during this time that Mr Twigger met and fell in love with his future wife, Connie, a spirited young woman from North Shields.

Born in Birmingham on February 28, 1923, he was 17 when war broke out and worked as a messenger for the Fire Service before joining the RAF Police a year later.

He spent the weeks leading up to D-Day converting old petrol cans into road signs to take to France.

A week before, the men were taken to a sealed area - as part of a massive cloak of secrecy - and were not even allowed to send messages to their loved ones.

However, they devised an ingenious scheme to post letters, which saw Mr Twigger pour sugar into the petrol tank of his Harley Davidson motorbike.

This gave him an excuse to take it to a garage in Dover and post the letters en-route. Unfortunately, it resulted in his beloved motorbike being replaced with an inferior model.

Mr Twigger arrived at Arromanches Beach in Normandy on D-Day plus one.

“By the second day the Army lads had pushed the Germans back,” he says.

“We spent a lot of time putting up fence posts and barbed wire. We also set up tents for a prison. “There was no time to be scared. We just had to get on with it.”

A few days later, the ambulance driver was taken ill and Mr Twigger was tasked with driving the vehicle to Brussels, where he helped take over a civilian prison and transported injured men to hospital.

The journey was treacherous, with German snipers still at large and the bodies of fallen soldiers lying at the road side.

“Although the Army had chased the Germans out of Brussels there were still some around,” he says. “When walking at night, you never knew when one would fire at you from a window.

“When we moved through France and later into Germany we would come across the body of a soldier from time-to-time.

“All the army lads had a tag with their name and number on and we would take it off before we buried them.

“We then made a cross out of wood and hung the tag on it so that the people who came to collect the bodies knew who it was.”

However, it was the same dangerous journey that led Mr Twigger to his future wife. Mrs Twigger, nee Dickens, started out as a heavy ack-ack gunner with the Royal Artillery but was a telephone operator in Brussels when their paths first crossed. Their wartime romance blossomed into a 65 year marriage and Mr Twigger eyes well up when he speaks of his late wife.

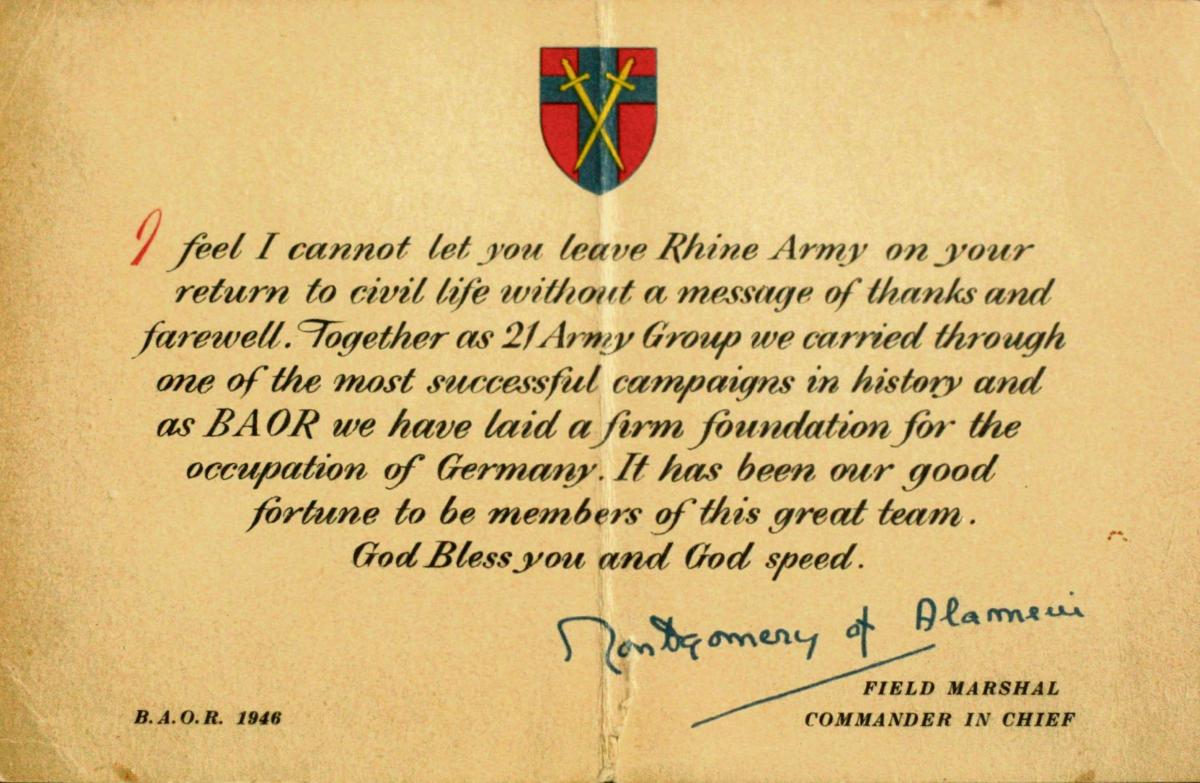

He is fiercely proud of a telegram she received from Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, commander of D-Day and the Battle of Normandy, thanking her for her service.

After Brussels, Mr Twigger moved to Germany where he served for four years before returning to England and a post as station sergeant at RAF Acklington in Northumberland.

On retiring from the forces, he worked at a builder’s merchants and later set up a sauna business.

He has never returned to the beaches of Normandy but has visited the war cemeteries.

“It was very upsetting,” says the soon-to-be great grandfather. “They were young lads, 18 and 19-years-old. They were far too young to die.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here