Fifty years ago today Martin Luther King Junior delivered his famous “I have a dream” speech. Lizzie Anderson talks to an eye-witness who treasures the memory of that historic day.

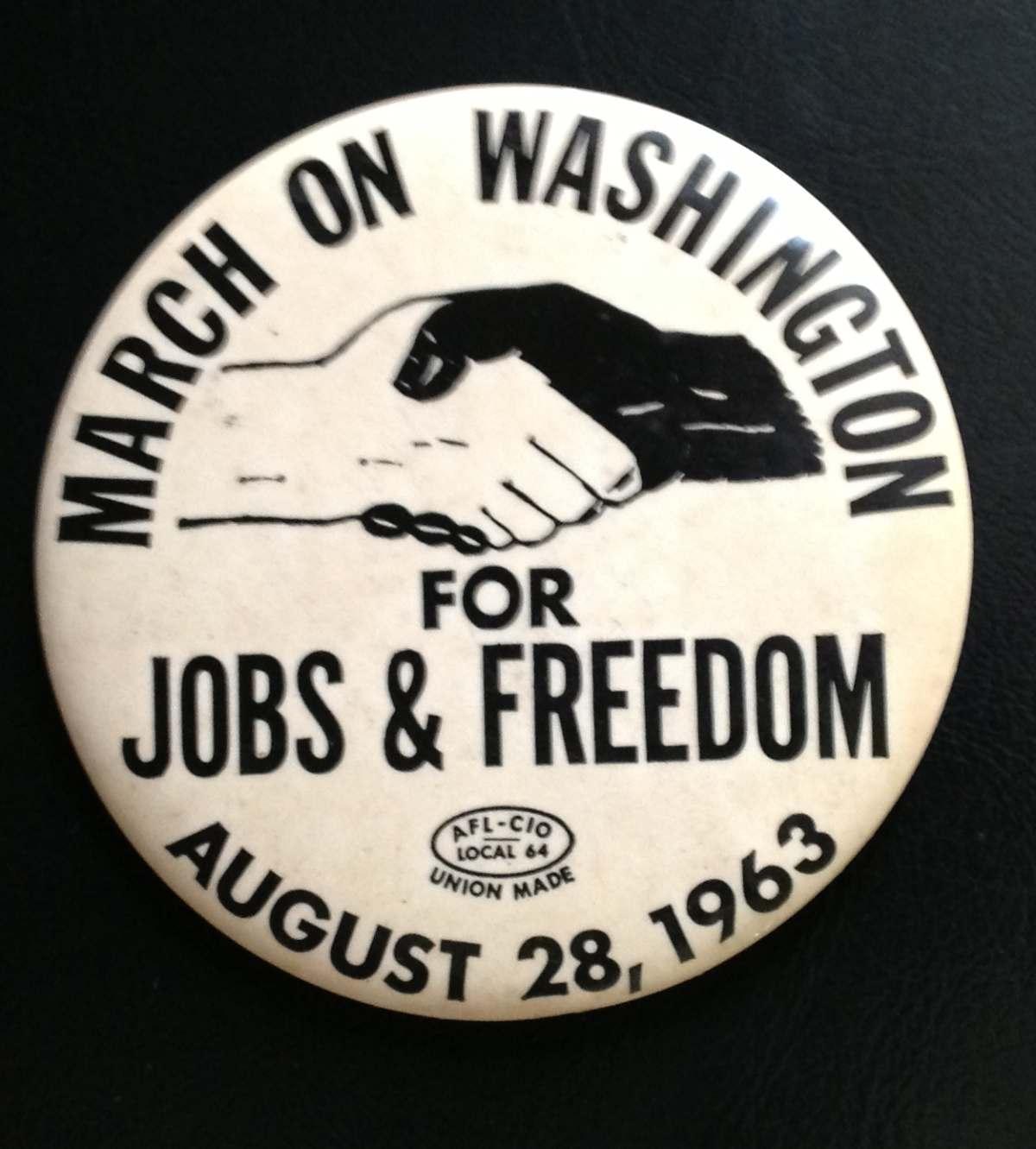

On August 28 1963, 14-year-old Candace Allen accompanied her father, step-mother and brother on the Washington March for Jobs and Freedom.

It was a stifling day and more than 200,000 people, black and white, gathered in front of the Lincoln Memorial to show their support for the proposed Civil Rights Act.

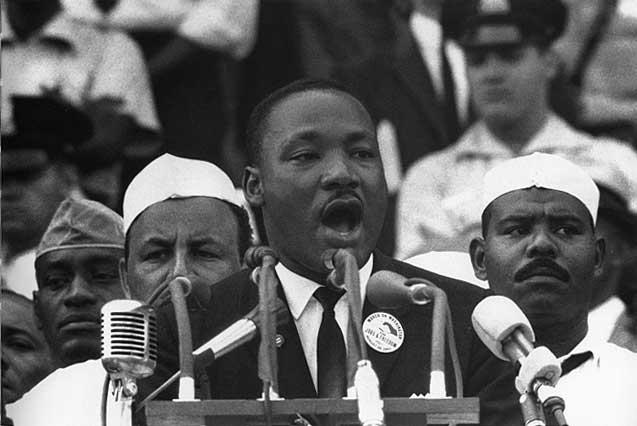

Many speakers addressed the crowd in the US capital that day but it was the words of the clergyman Martin Luther King Junior that captivated the audience and still resonate across the world half a century later.

In his “I have a dream” speech, King outlined his vision of a world of racial equality.

It was a defining moment of the United States civil rights movement but for many in the audience his message was much more personal. King was speaking straight to their hearts.

“I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations,” he said.

“Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. And some of you have come from areas where your quest – quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality...

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character.”

And, today, fifty years on, Barack Obama, the current and first black president of the US, will serve as a living symbol of King’s dream when he delivers a speech from the same spot.

Ms Allen, now 54 and living in London, remembers the excitement she felt when she heard King’s words reverberate around the National Mall.

“I remember that it was very hot and there was a real sense of excitement amongst the crowd,” she says.

“As African Americans we were all involved in the civil rights movement, some more active than others, but the fact that we were black and in America at that time meant we were involved.”

Over the years, Ms Allen, a successful film director and author, has read and re-read King’s speech.

“I carry the words in my heart always,” she says. “Even now, the speech gives me goose bumps.

“I have also kept my pin badge. It has travelled back and forth across the Atlantic with me.”

Born and raised in Stamford, Connecticut, the Allens were one of just a few black families living in their neighbourhood.

The young Ms Allen was shielded from the entrenched racial segregation of the Southern states but she experienced prejudice in more subtle ways.

From a pastor quietly suggesting her family would be “happier” at a different church; to being prevented from taking part in ballroom dancing classes, she was constantly reminded of the fact she was different.

The Washington March was not the first time she heard King speak. Her parents were close friends with Jackie Robinson – the first African American baseball player to break the sport’s colour barrier.

The Robinson family, who lived nearby, held jazz music parties to raise funds for the civil rights movement and King himself delivered a speech at one such event.

“I never got to speak to him personally but I remember he was very charismatic,” Ms Allen recalls.

In the mid to late 60s, Ms Allen became a civil rights activist and took part in a series of protests while studying at Harvard University.

During this time, she had doubts over the effectiveness of King’s non-violent approach, preferring the more combative views of Malcolm X.

However, news of King’s assassination on April 4, 1968, shook her to the core.

“I was home on Spring Break when King was assassinated,” she says. “I was driving up the hill when I heard and I almost ran off the road. I was utterly devastated. He was the best of us and the best of America.”

She describes the 1960s and 70s as an unsettled time and vividly recalls the stab of fear she experienced when she passed a road sign for Birmingham, Alabama, the scene of the racially motivated church bombing that killed four black children.

Music proved a tower of strength to her and her fellow activists.

On the day of King’s famous speech, his supporters marched through the streets singing old slave songs, while songs by black artists such as Nina Simone that tackled racial persecution became instant anthems.

She adores jazz and soul music and, after a successful career in the film industry, which saw her become the first female African American member of the Hollywood Director's Guild, she is exploring this passion as an author.

In her latest book, Soul Music: The Pulse and Race of Music, she asks whether the pitched battles between “our music” and “their music” of her youth are alive today.

Ms Allen remains committed to the dream King shared with the world on that sweltering day in 1963 and, while she recognises progress has been made, she believes there is still a long way to go to eradicate racism.

Quoting from King, she states: “1963 is not an end, but a beginning.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here