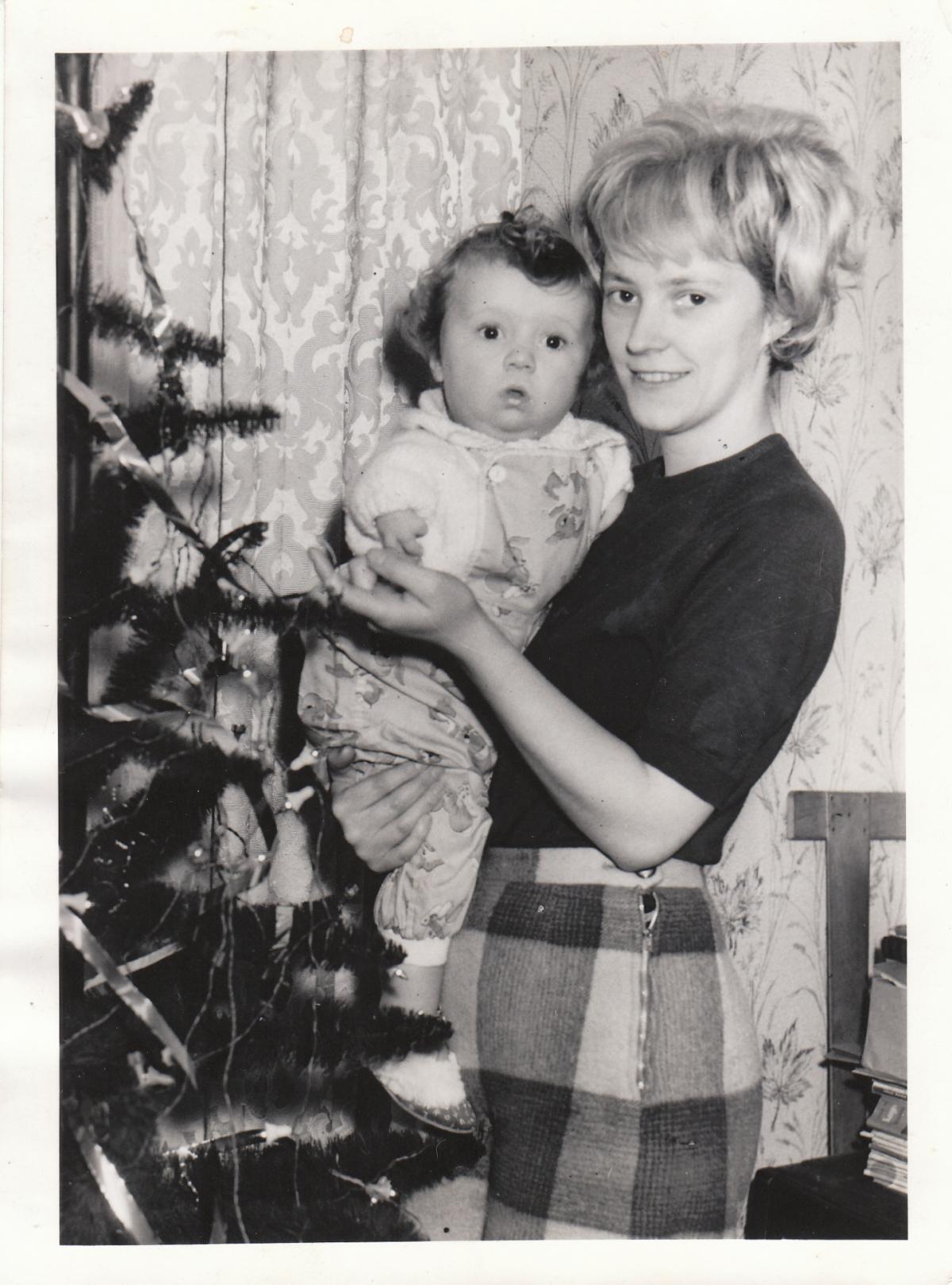

EVEN now, 54 years on, Irene still needs to wipe away tears and take a deep breath as she remembers the day she gave birth to her son – January 2, 1962.

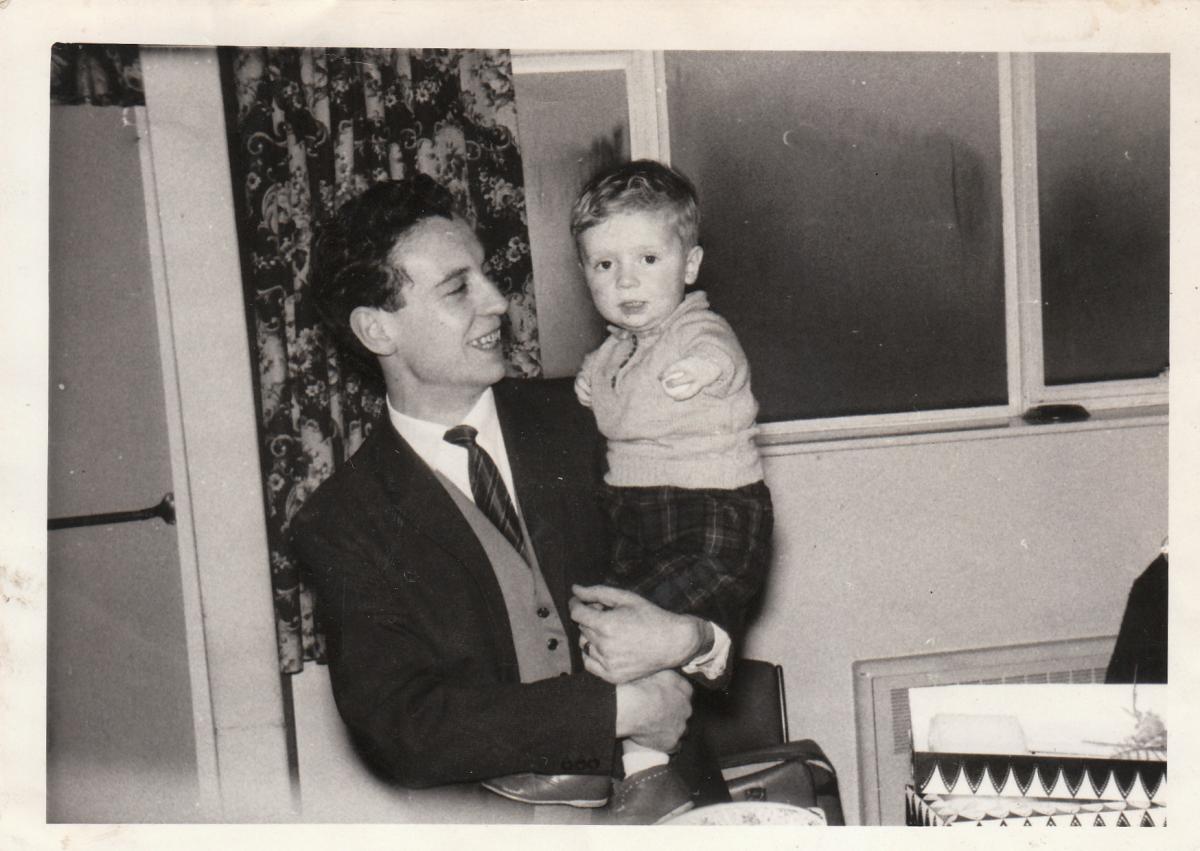

Derek was a honeymoon baby, born at the outset of a devoted relationship which had first been kindled when Irene met a boy with the grand-sounding name of Barry Ward-Thompson at Vane Tempest Youth Club, in County Durham.

The first question he’d asked Irene was “Where do you live?” – checking he wouldn’t be taking too much on if he offered to walk her home. Luckily for him, Belmont wasn’t too far.

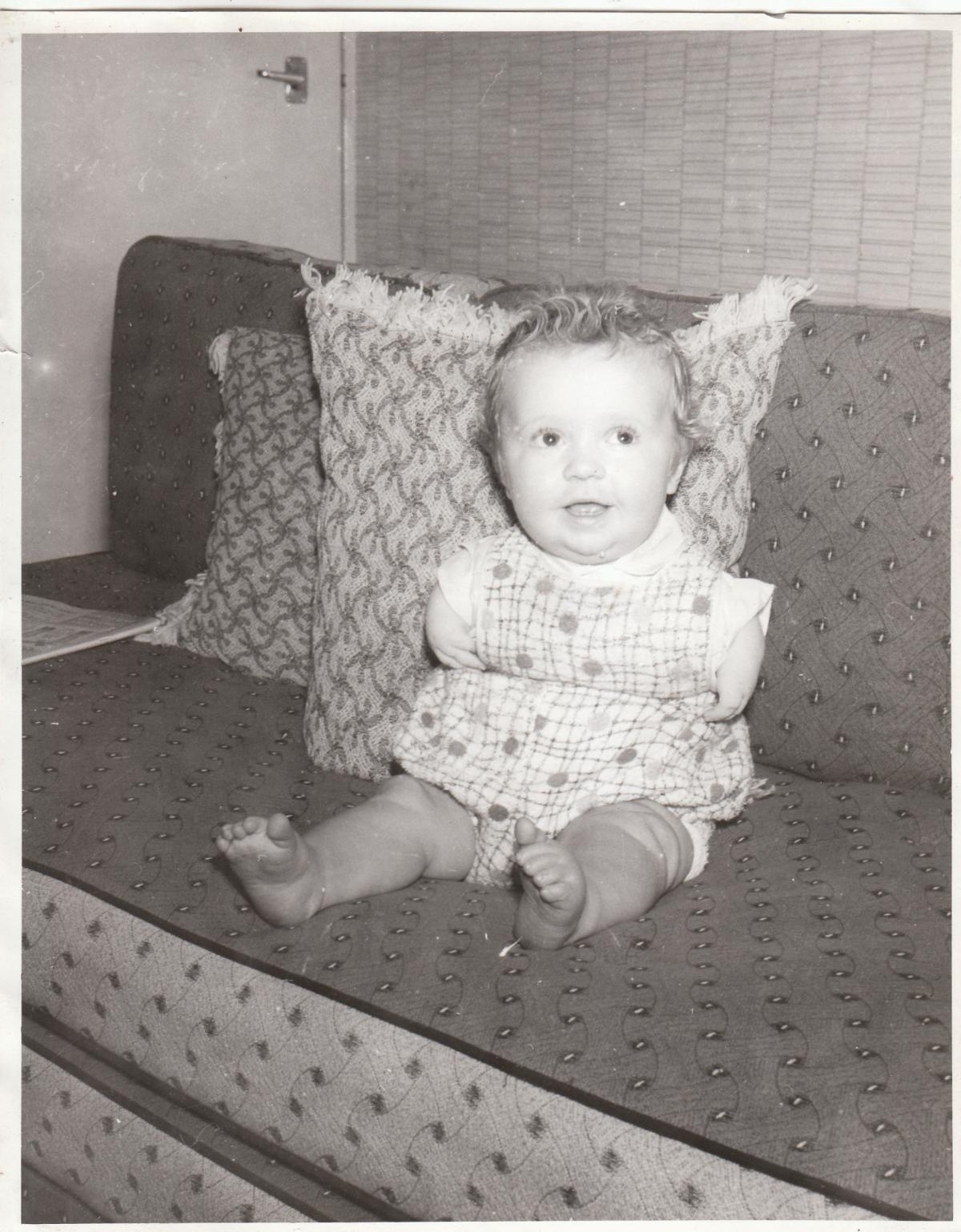

Nurses took baby Derek from Irene the moment he was born. She and the baby needed to rest, they said. It wasn’t until the next day that Barry solemnly told Irene that their baby had been born with deformities – two short arms. No explanation was given, it was just one of those things that they’d have to live with. Derek would never be able to walk or be able to do anything for himself, they were told.

“It was an awful moment, a terrible responsibility to have to face,” says Irene, speaking softly from the front room of her flat overlooking the grounds of the old Sherburn Hospital, near Durham.

It might have torn the couple apart but instead it brought Irene and Barry closer together. Their baby was disabled but he was lovely – a good sleeper, with an infectious laugh, and easy-going personality – and they were determined the medical staff who had predicted such a depressing future would be proved wrong.

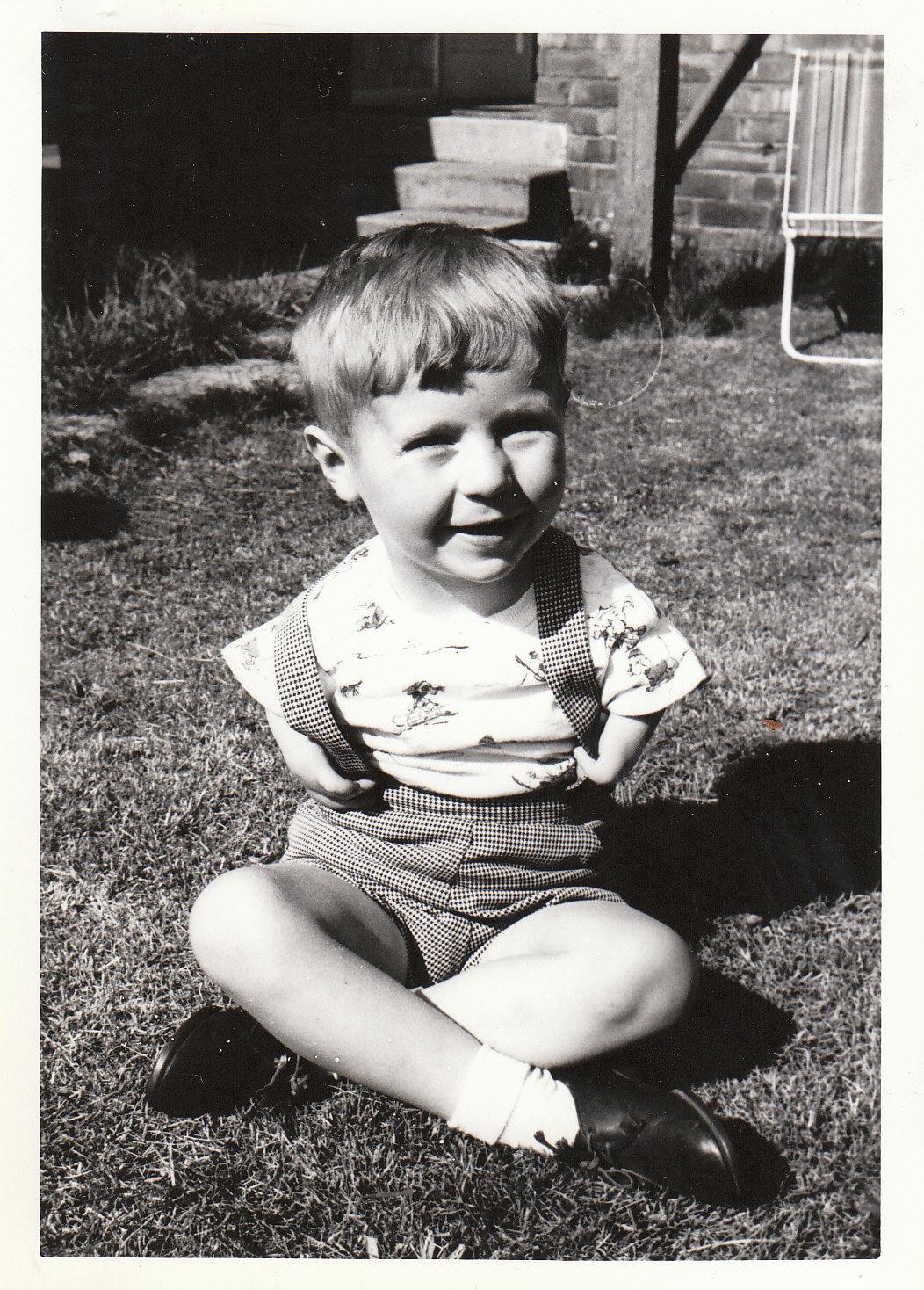

“Derek’s natural inclination was to use his feet for everything but we persisted in getting him to use his hands as much as possible and he learned quickly,” remembers Irene.

Six months passed before the terrible truth about Derek’s disabilities was revealed. A family friend who was a chemist showed Irene and Barry an article in the Lancet medical magazine, drawing a link between deformities in babies and a new drug called Thalidomide. Irene had been prescribed Thalidomide by her doctor when chronic morning sickness struck during her pregnancy. She couldn’t keep anything down, couldn’t even bear smells, and was told she might lose her baby if she didn’t get help.

The Lancet article gave Irene and Barry the first indication of what had gone so terribly wrong but it was only when Sir Harold Evans, campaigning editor of The Northern Echo, began to write about the scandal that progress began to be made.

“We were always Northern Echo readers and through the paper we began to realise that we weren’t isolated,” Irene recalls. “There were others in the same position and we started to contact each other. There was a little boy at Spennymoor, and a girl at Wheatley Hill. Just knowing that we weren’t alone and that someone was on our side meant so much.”

The families formed a help group, meeting regularly, fundraising for research, and sharing experiences. For example, Irene had made it easier for Derek to dress himself by sewing Velcro down his shirts and it was a tip which was passed on to other families.

Irene and Barry persisted in their determination to lead as normal a family life as possible. A daughter, Helen, was born in 1966 and Derek was sent to Belmont Primary School.

“He didn’t stand a chance,” sighs Irene. “He was in a class of 46 and he was just lost.”

The couple decided that they had to scrape the money together to send their son to the fee-paying Durham High School, which had just started taking boys. With Barry forging a career as a trainee architect, and Irene working as a secretary at Durham University, it wasn’t easy but the class sizes dropped from 46 to 16, and Derek began to flourish.

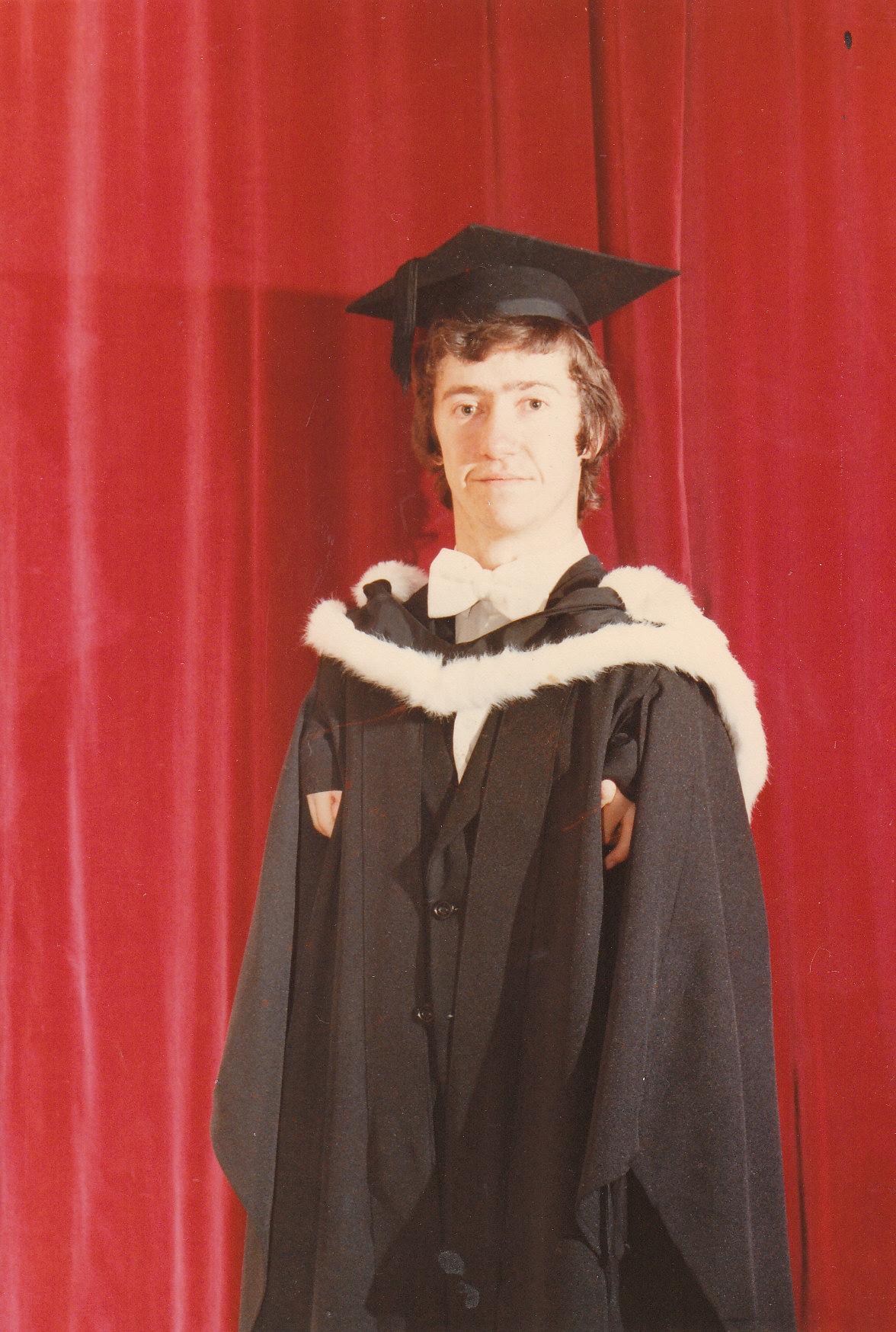

When he was eight, he went with his dad to see a lecture by the famous astronomer, Sir Patrick Moore, at Sunderland Polytechnic and a spark was ignited. From Durham High School, Derek went to Durham Choristers and he ended up with a place at Oxford, studying physics and maths. There was no stopping him now: Masters and PhD at Durham University; post-doctorate at Cambridge; a post at Edinburgh Observatory; then Professor of Astronomy at Cardiff.

His father died in 1992 and Irene remarried – to Jim Milburn – in 1999. Derek, who has a passion for the sport of rowing, still sponsors the Barry Ward-Thompson Trophy at Durham Regatta every year.

The pride Irene has in Derek is evident in every word: “Who’d have thought he would go so far – and we’ve never forgotten what Sir Harry and The Northern Echo did for us as a family,” says Irene.

After leaving The Northern Echo to join The Sunday Times in 1967, Sir Harry continued his campaign to expose the cover-up by Distillers, the drug company which had distributed Thalidomide to the NHS.

“Sir Harry kept fighting until there was a trust fund established for the families. It had gone on for 12 years and all the parents had to agree or it was null and void,” explains Irene.

“It was paid on a points system – so many points for an arm, so many for a leg. I suppose it was quite brutal really but it accumulated for Derek and that was a relief because we knew, whatever happened to us, he would be OK. The money was used to buy him his first adapted car and his first house. But do you know, despite everything that happened, they never once said sorry.”

Derek now lives happily near Preston with his wife, Jane, and and two sons, George, 15, and Peter, nine. He has completed the Great North Run four times, is a friend of fellow astronomer Brian May, the Queen guitarist, and has risen to be Head of Maths, Physics and Astronomy at the University of Lancashire.

The boy the medics had predicted would be unable to achieve anything had aimed for the stars and reached them.

It is an inspiring life story – and the part played by Sir Harold Evans, and The Northern Echo, has lived with his family for half a century.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel