LAST week’s column recorded the 80th anniversary of the world record breaking steam train Silver Jubilee, bright shining after all these years. Roger Jennings applies a light brake.

What of Papyrus, he asks? Well he might.

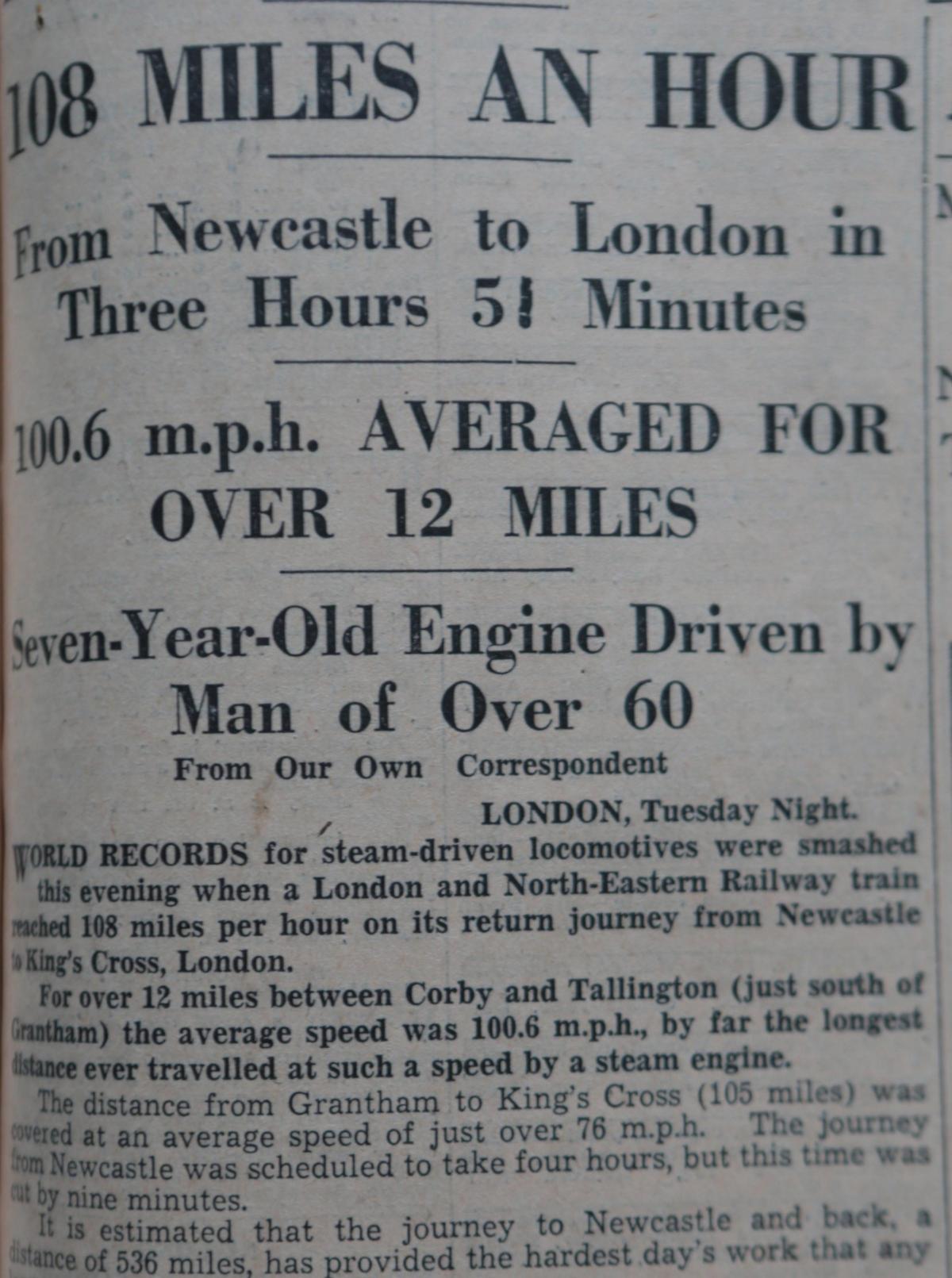

Papyrus was an A3 class locomotive which, nine months before the Silver Jubilee entered service, had itself very much set the pace. It was March 5, 1935 and it dominated the front page of the following morning’s Northern Echo.

The LNER was determined to resist the allure of diesel traction, particularly the crack German express known – at least over here – as the Flying Hamburger.

Papyrus, one of a class designed by Nigel Gresley, but altogether less well remembered than the streamlined and Gresley-inspired Mallard, was chosen to prove that it was possible to cover the 268 miles between Newcastle and Kings Cross in under four hours – the fastest timetabled train took five hours and seven minutes.

Papyrus was a coal fired John the Baptist, making the paths straight.

On March 5 she’d already sped from London to the Tyne, before heading south again – using eight tons of coal over the 536-mile round trip.

“The hardest day’s work any locomotive in the world has ever been called upon to do,” said the Echo next morning.

The engine, a headline noted, was seven years old. Harry Sparshatt, the driver, was “over 60”.

For 12 continuous (and downhill) miles near Peterborough, the six-carriage train averaged 100.6mph – “by far the longest distance ever travelled at such a speed by a steam engine".

The top speed was 108mph, the average 70.4mph; 300 miles were run at 80mph and the journey was completed in three hours 49 minutes despite delays because of an accident near Doncaster. All were world records.

“Papyrus rode like a Derby winner all the way,” said Mr C C Jarvis of Darlington, the man at the speedometer, doubtless remembering that engine 2750 was named after the 1923 winner of the Epsom classic.

“Just an ordinary job,” said driver Sparshatt, but the Flying Hamburger was mincemeat.

Roger Jennings has on his wall a specially commissioned painting by the splendid railway artist John Wigston – now in Stanhope – of Papyrus at Durham on that epochal day.

The locomotive itself was withdrawn in 1963 and – unlike some of her more feted contemporaries – cut up, cruelly, on the Clyde.

ANOTHER PS to the Silver Jubilee celebration and, perhaps inevitably, it concerns one little duck.

Earlier columns have noted both that the planned statue of Sir Nigel Gresley at Kings Cross station had a mallard at his feet and that the mallard – a nod to the name of his most famous locomotive – had caused feathers to fly.

After objections from Sir Nigel’s grandsons, the Gresley Society decided that the duck must go. Ahead of last Saturday’s annual meeting, Society members – of whom the column is one – received a letter from someone with the email address 60017SilverFox, coincidentally one of the Silver Jubilee locos, calling for the bird’s reinstatement.

It talked of untruths, misrepresentation and abhorrent insults, claimed that the Society had become a “laughing stock” and called for a vote of no confidence in its governing body. “They have driven a coach and horses through the Charity Commission guidelines on decision-making,” it added.

The statue will be unveiled in April.

REMAINDERED from last week’s railway recollections, Peter Chapman sends the BR left luggage tariff from 1974 – inclusive of VAT.

For 17p for the first two days – and a further 17p a day thereafter – passengers might deposit everything from a bicycle to a billiard cue, a golf bag to a gramophone (portable), a typewriter to a tuck box.

Perhaps for the benefit of absent minded mathematicians, a T-square might be accommodated, too.

The 27p charge for larger items included motor cycles (with or without sidecar), television sets, violincellos “and other musical instruments”, sewing machines and even ice cream barrows.

British Rail, it seemed, had left nothing to chance.

IN a small sort of a way, retired teacher Joe Coates usually writes of railways, too – specifically the North Bay miniature railway in Scarborough to which he’s devoted a series of children’s stories.

In time for Christmas, he’s now published There is Something Special Tonight in Bethlehem, the first in what he hopes will be an illustrated series of Bible stories for youngsters, told traditionally.

Joe, Shildon lad originally, has already been telling the tale at schools in the Scarborough area. Details on northbaytales.com

Kitchen where

DOWNTON Abbey devotees may have picked up a familiar name in the script the other Sunday: Mrs Patmore’s tea room was in Haughton-le-Skerne, hitherto better known as a suburb of Darlington.

“I drove through it and couldn’t see the team room anywhere,” reports Darlington councillor Alan MacNab.

Downton has form. We’ve observed before that Eryholme – a hamlet on the south bank of the Tees – has been mentioned in the programme and so, says Alan, have Thirsk, Ripon and the Broughs who were lords of the manor around Catterick Village.

“I hope that people don’t descend on Haughton hoping to find Mrs Patmore’s,” says Alan, but there’s a precedent for that, too.

The late Ray Moore, whose Radio 2 programme was on before Terry Wogan’s, was given to the observation that a certain record was the best thing since Rudyard Kipling made his exceedingly good cakes.

Finally, Moore received a call from the curator of Kipling’s home – Batemans, in Sussex – asking him to desist. “Thousands of people,” says Alan, “had arrived at Batemans asking to be shown the kitchens.”

TELEVISION of a slightly older vintage, we joined last week a little reunion of former Tyne Tees people. It proved a happy occasion.

Familiar faces included Peter Holland, Luke Casey, Andy Kluz, Paul Frost and Ruth Pinder – six children since last seen on screen 25 years ago, but in pretty good shape, nonetheless.

Whether for better or worse, none appeared to be recognised. Sic transit gloria, as they say elsewhere.

Frosty, self-styled grumpy old git, has recently written a book called Where’s My Glasses, sub-titled “A squint from middle-age.” Basically it’s about all the things which irritate you when you get to 60, he says.

Among others present was the affectionately remembered weather man Bob Johnson, he who smuggled the word “dreich” southbound in his sporran.

All went well until one of the company asked him the long range forecast for Christmas. “White,” screamed Bob – or something closely akin – as he fled to the sanctuary of the gent’s.

HOME again, Peter Holland sends a photograph of a sign outside the Fleece Inn, in Northallerton, potentially sub-titled What the Dickens. Wasn’t it Morecambe and Wise who dined out on The Play What I Wrote? “The great man’s quill would have gone all a-quiver,” says Peter – and here’s the written evidence.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here