THE story so far: Thirsting after knowledge at the North-East launch of the Camra Good Beer Guide, last week’s column bumped into a gentleman wearing a T-shirt with the message “Harry Watts: Forgotten hero.”

“If I’d known you’d be so interested, I’d have ironed it,” said Robin Sanderson, the Sunderland and South Tyneside Camra official in question.

But who was Harry Watts, and why had he been forgotten? It proves to be not so much a T-shirt, more a book review.

Harry Watts was born in Sunderland in 1826, youngest of five children brought up in a tenement cellar which frequently flooded. Not totally forgotten, he does have a Wikipedia page – “Known for: saving livers”, it says and might have added a line about those in peril on the sea.

Andrew Carnegie, the great Scottish- American philanthropist, supposed Watts the bravest man he ever met – “the most ideal character of any man living on the face of the earth” – and when the ancient mariner was 85 awarded him a 25 shilling pension for the rest of his life.

Alfred Spencer, the author of a 1911 biography, claimed that Watts personally had saved 36 lives, plus a horse and a dog, in 28 separate incidents. As a Sunderland lifeboatman, he helped in the rescue of another 120.

Sunderland Museum supposes the figure to be “over 36” – why do people write like that, how many is “over 36”? – Robin Sanderson thought the figure 43. “He just always seemed to be in the right place at the right time,” he said.

Horrible Histories author Terry Deary, Sunderland born and proud of it, admitted last year that he hadn’t heard of the home town hero. “It seems our Irish terrier knows more than I do. Embarrassing,” he wrote.

On any account it’s a remarkable story but, unlike so many of those encountered by Harry Watts, we must attempt not to go overboard.

HARRY started work in a pottery aged nine, paid 1/6d a week, and at 14 went to sea. His first rescue happened on his first voyage, to Quebec; by the time he was 19, he’d saved four more. Mostly they seemed to be boys, mostly fallen from a ship or from the quayside.

On one occasion in Sunderland, however, he saved a woman trying to commit suicide. “Let me be in, let me be in,” she pleaded, but clearly had roped in the wrong rescuer.

“Nay,” said Harry, “aa’ve had ower much trouble gettin’ thee oot.”

His gallantry seems at first to have gone unrecognised – perhaps no one made the connection – and didn’t even make the local papers until 1866. Thereafter recognition came rapidly. “A particular penchant for saving lives,” an awards ceremony heard in 1868.

By then his total was 28.

As a young man he was said to enjoy a drink – as his biographer perhaps euphemistically puts it – but after a hard night and a conversion experience, he became both a committed Primitive Methodist and a tireless temperance campaigner.

Been there, done that, but perhaps might not have wanted the T-shirt.

Later he was a River Wear Commission diver, completed his last saving grace when 66, retired at 70. “He is an optimist to his fingertips,”

wrote Spencer, “always bright and cheerful, so earnest and vigorous even now in his 85th year that it is good to be in his company for a while.”

Last year a second biography was written by David Simpson, formerly familiar on The Northern Echo, and Richard Callaghan. It noted a weatherbeaten and indecipherable headstone in Grangetown cemetery, Sunderland. “A poor epitaph for a remarkable life.”

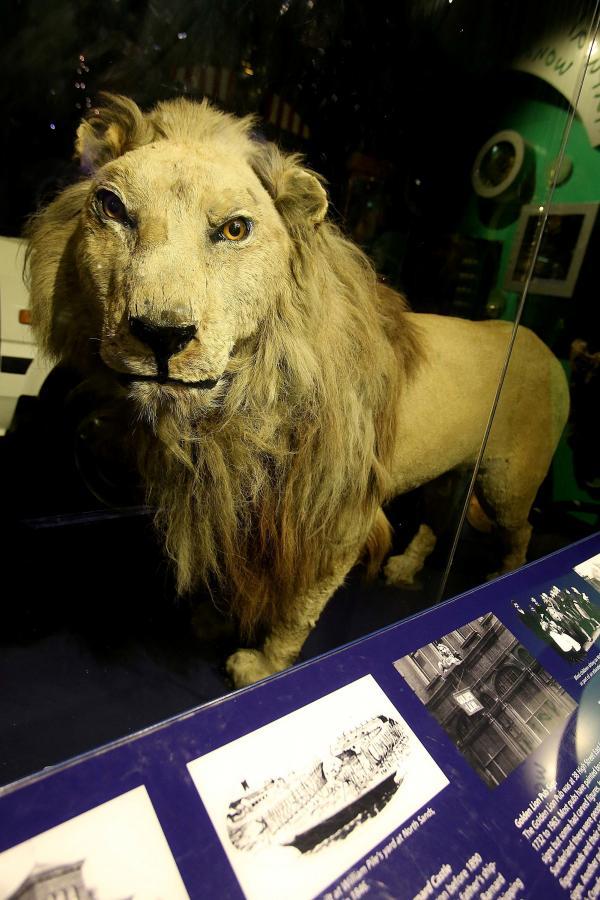

SO the column takes itself off to Sunderland Museum, to buy the book and to view a “small” Watts exhibition, and is waylaid by Wallace the Lion. Wallace is King of the Museum, or at least supposes himself to be. A sound loop tells his story; a push button, conveniently toddler height, plays – fairly ceaselessly – The Lion Sleeps Tonight.

Stuffed, Wallace may no longer roar, but these days he tweets. The museum shop sells soft toy Wallaces, too, about as fearsome as Sooty with sore gums.

Like Wallace, Martino Maccomo worked for the Grand National Star Menagerie and was a bit of a national star himself.

His show, it’s said, involved chasing 20 angry lions and tigers around a cage, while armed with a whip and – perhaps more usefully – a gun. “Not for the faint-hearted,” it was supposed. The animals are said to have got wilder and wilder, as well, it’s reasonable to assume, they might have done.

In 1868, while playing to packed houses in Sunderland, Maccomo was mauled by Wallace. Wasn’t the beast in Albert and the Lion called Wallace, too?

Though the trainer survived, he died in 1871, aged just 36, from rheumatic fever – which must almost have seemed an anti-climax – and is buried, for some reason in the Commonwealth War Graves section, in Bishopwearmouth cemetery.

Wallace, presumably also dead, was bought by Sunderland Museum in 1879 and, roaring trade, has had pride of place there ever since.

SO back to Harry Watts, and to Terry Deary. In 2012, Terry helped make a BBC Inside Out slot about Watts and by way of promoting it, had a piece in the Telegraph.

“Last winter,” he wrote, “a fire service crew refused to enter an icy lake to rescue a man because health and safety rules said that they shouldn’t if the water came over their knees. What would Harry Watts have done?”

Things have moved on since then. There’s a blue plaque near Sunderland lifeboat station.

“They didn’t ask me to its unveiling, but that’s all right,” says Terry, who believes the reason for Harry Watts being forgotten is that he died in 1913, just before the Great War.

“There were very many other heroic people to remember, too.”

There’s a seat with his name on it at the Empire Theatre – coincidentally staging The Lion King this week – and a photograph at the museum, medals filling his chest like a portmanteau.

Watts was also put forward when the city council invited names for a new square, though it won’t be appearing. “He made the long list, but not the shortlist,” says a council lady.

“The theme was really about keel boats.”

Then there’s a beer festival T-shirt, freshly ironed for the photographer. “Harry Watts may still not be particularly well remembered,” says Terry Deary, “but he’s better remembered than he was two years ago.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here