After three-quarters of a century, Heartbreak Hill’s secret is about to be revealed.

EXTRACTS from an unknown work by one of Britain’s foremost 20th Century composers will be broadcast on Radio 3 a week on Saturday. Readers are urged not to switch off, for it is a quite remarkable story.

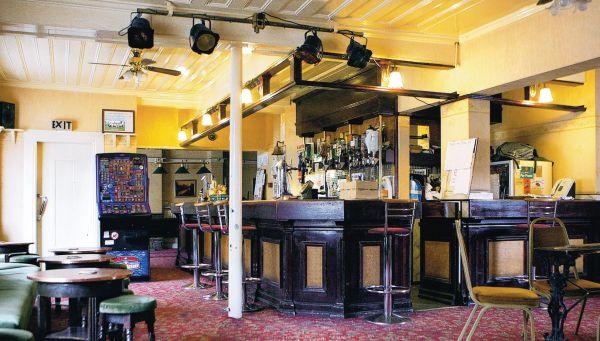

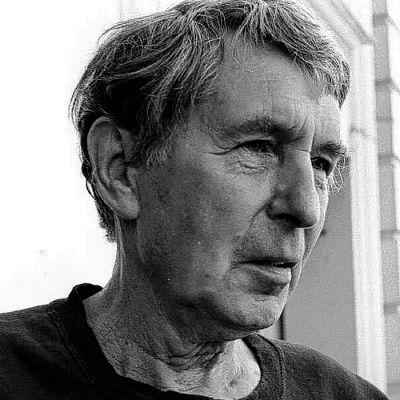

The composer is Sir Michael Tippett – intellectual, homosexual, Trotskyite, conscientious objector, musical genius. The venue is the bar of the Station Hotel in Boosbeck, east Cleveland.

John Lawson, one of the men who really knows the score, recalls that the pool games and the patter continued as they rehearsed. “To be fair, when the BBC asked for quiet they got it for the recording.

“If it had been down south it would have been in some fantastic opera house somewhere, but the Station was ideal, really.”

Boosbeck’s near Saltburn, former ironstone mining country. When unemployment rose to 91 per cent in the 1930s, many men said almost literally to be starving to death, the Pennyman family from nearby Ormesby Hall gave land near Skelton Castle in the hope that it could be turned into smallholdings for the jobless.

First it had to be cleared. “It was just moorland, huge stones and tree roots, enormously difficult to work,”

says John Lawson.

They called it Heartbreak Hill.

Since the malnourished miners were unable to complete the job, students from Germany and Scandinavia were brought in to live and work alongside them.

The unknown Tippett, then a Communist party member and friend of Guardian journalist David Ayerst – one of the scheme’s instigators – was brought in to add a bit of culture in the evenings.

“He lived for about a year with another feller over a shop in Boosbeck,” recalls John. “It probably changed a lot of attitudes on both sides.

“I think he may have started working on Heartbreak Hill, thought sod this for a lark, and in 1933 he co-operated with the miners on a production of The Beggars’ Opera.”

The following year, Tippett went further. He wrote the first opera of his own, called Robin Hood, about Cleveland’s worked out ironstone miners:

God bless our valiant Robin Hood

And never may he swing

Who fights the battles for the poor;

The outlaw shall be king.

It was performed, one night only, in the now-demolished Boosbeck church hall, next to the Station.

Thereafter none ever heard of Robin Hood; it was like he’d just vanished over Heartbreak Hill.

JOHN’S part of Iron Awe, an arts group led by former Lackenby steel worker Mike Benson who’s now director of the Ryedale Folk Museum at Hutton-le- Hole, near Helmsley.

“I got into my 40s before I realised that no one was celebrating our heritage,” says Mike. “The story has almost been painted out. It’s time to take the paint off, to teach about it in schools and to make it much more widely known.

He was told about Tippett and the Boosbeck connection by Tony Nicholson, an academic at Teesside University. “The more you get into it, the more fantastic it becomes.

“There was a girl at the recording whose father and grandfather had all lived in the village and until then they’d never even heard of Robin Hood.”

The group had already made two films, using school children, about local life and hard times. Now they plan a third, about Heartbreak Hill, and hope for funding to perform the complete opera using local people.

John, from nearby Loftus, memorably supposes it to be “a bit like The Floral Dance meets Robin Hood.”

Tippett, who died aged 93 in 1998, is said so greatly to have disliked it – he thought the 90-minute work “juvenile”

– that he destroyed the score and declined permission for further performances.

“He said it didn’t fit in with his later work. He called it a piece of nonsense, or something like that,”

says John.

“We were only given copies of three of the songs. There’s quite a lot we’ll need to add if we’re going to do a full production.”

Parts of it were cannibalised, however, for Tippett’s Suite for the Birthday of Prince Charles. “Fancy,” says John, “Boosbeck one day and the heir to the throne’s birthday the next.”

Local historian Mark Whyman had hoped to find the sheet music among the Teesside archives at Ormesby Hall. Though he found a piece of paper with “Robin Hood” on the top, it was proved not to be Tippett’s writing and to be from the 19th Century.

Mark’s philosophical. “My claim to musical fame now rests on my being selected by the Guinness Book of Records for my total lack of musical ability, having been thrown out of the infant school orchestra for repeatedly dinging my triangle at the wrong moment.”

Boosbeck attracted just four or five villagers to the first rehearsal, a few more to the second – “I had posters all over,” says John – and by the time of last week’s recording had, he admits, roped in a few ringers. The keyboard player used music written in Tippett’s own hand.

“I thought my own contribution was very good until it was played back. It’s a pity I was out of tune, but the BBC people from London still seemed very happy,” says John.

A snippet of Tippett, Robin Hood rides again at 12.15pm on November 28, part of the Music Matters programme.

One thing’s certain, says John Lawson, Radio 3 will never have had so many listeners in Boosbeck.

Inferior decoration

NOT what you’d call an emergency, but last week’s column was reckless, nonetheless, to traduce engine No 999. We’re back to Rocket science.

The locomotive stands in a Chicago museum next to a full-size model – made by 1930s apprentices at Robert Stephenson’s locomotive works in Darlington – of Stephenson’s finest.

Darlington exile Brian Madden had visited the museum, expressed astonishment at seeing the Rocket, supposed its neighbour to be “inferior”.

Inferior? Paula Ryder in Bishop Auckland rides full-steam to 999’s defence.

The loco, built with Stephensondesigned valve gear, went into service in 1893 on the Empire State Express, a fair-old flyer between Chicago and New York.

Almost immediately it is said to have reached 112.5mph, hauling four wagons slightly downhill – though admittedly, concedes Paula, the timing was between two mile posts on the conductor’s “trusty railway pocket watch”.

The previous night, it had been timed over five miles at a constant 102.8mph. “Those with knowledge of such matters seem to think those speeds a little more credible,” adds Paula.

They called 999 the Queen of Speed. “The fastest man-made invention of its time and the first object on wheels to exceed 100mph,”

says Wikipedia.

The Queen of Speed, of course, was eventually overtaken. Before retirement in 1952, she was shunting milk wagons in uptown New York.

An inferior occupation, if ever.

WE’D wondered how a Darlingtonmade Rocket replica came to be standing about in Chicago Science Museum. Railway preservationist and former Darlington councillor Barrie Lamb provides the answer.

Robert Stephenson’s locomotive works moved from Newcastle to Darlington in 1902. In 1929, Henry Ford – owner of much that he surveyed – tried to buy the 100-year-old remains of the Rocket but his representative was advised to contact Stivvie’s about a replica.

While that one was being built, says Barrie, a further three were ordered – for New York, Chicago and the Science Museum in South Kensington.

A total of seven Rockets have been built, says Barrie, these four in Darlington.

Then there was the original, followed by Stockton and Darlington engine No 7 – another example of Rocket propulsion – and the replica masterminded by Mike Satow for the 150th anniversary.

That’s the one now in Beamish Museum.

Wax on, wax off for a good cause

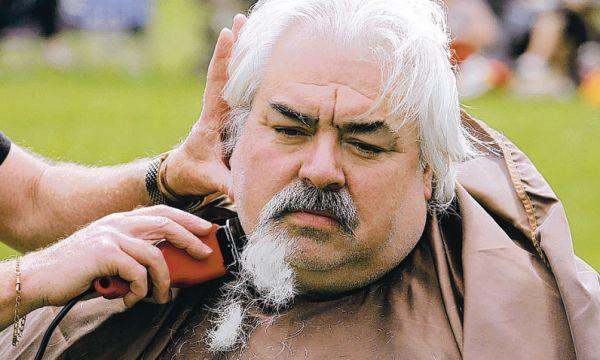

REMEMBERING all that they say about benevolence’s browtings up, we attended the mayor’s charity dinner in Shildon. It was a thoroughly enjoyable occasion.

This one was chiefly to help town causes. Gareth Howe, the admirable mayor, is also much involved with fundraising for Help for Heroes, which fights for our soldiers.

A few months back he had his 35- year beard ceremonially shaved, a growth so resilient that already the new one is on its third trim.

Now he plans a body wax, hopes to raise thousands and is trying to find the biggest workmen’s club in County Durham in which to undergo the ordeal.

“It’s not that I mind doing it, I just don’t think we should have to,” said the mayor, a former Royal Anglian Regiment man.

There are two potential problems, one that Gareth – like Esau – is an hairy man. The other – how may this delicately be put? – that he has rather a lot of body to wax.

“Just think how many candles that’s going to take,” said fellow councillor Gary Huntingdon, mischievously.

They’ve even been contemplating selling the rights to howk the waxed pads off again. Gareth’s a Liberal democrat: the other lot will be charged double.

YET closer to home, details have been confirmed of centenary celebrations for Timothy Hackworth primary school in Shildon – officially opened on February 12, 1910, universally and affectionately known as Tin Tacks.

“There’s a huge feeling for the place,” says school business manager Pauline Crook, herself – like all the best people – a former pupil.

It was opened by Mr M Watson JP who thought it “a magnificent pile of buildings”, the 48th new school in County Durham in the previous six years and with a further 25 under construction.

Festivities begin on February 8, an Edwardian class room in full vigour throughout the week and, on the Monday, an actor playing Hackworth, the great railway engineer.

On February 11 the school presents Tin Tacks Has Talent – afternoon and evening – and on centenary day Jane Hackworth Young will unveil a plaque as part of an Edwardian fun day.

Each pupil will also receive a professionally- produced history of the school. An open day – open to all – will be held on Saturday, February 13. “They’ll see an awful lot of changes,” says Pauline.

ONE of the emails about the centenary also noted the death, on his 63rd birthday last week, of Ken Logan – not a Tin Tacks man but a contemporary at Bishop Auckland Grammar School. “We’re getting to the front of the bus,” wrote another school friend, gloomily. They’re just going to have to fit more seats.

PROMOTING Bishop Auckland Music Society’s Christmas concert – with Crook and Weardale Choral Society, Auckland Castle, December 16 at 7.30pm – last week’s column said that tickets were £16. It was a misreading; they’re £10 – including “seasonal refreshments” – from Peter Cooper, 44 Archery Rise, Durham, DH1 4LA or from Cameo Art in Newgate Street, Bishop Auckland.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article