William Harbutt, inventor of Plasticine, has given millions of children around the world hours of enjoyment. The column delves into his formative years spent in North Shields.

HE helped shape the lives of millions of youngsters, now William Harbutt – the man who invented Plasticine – is at last being honoured in his home town.

Model citizen? “I have to admit that my first reaction was William Who?” says John Fleet, town centre manager in North Shields. “Everyone’s heard of Plasticine but very few of William Harbutt.”

His brainchild has nonetheless proved durable, as well as pliable.

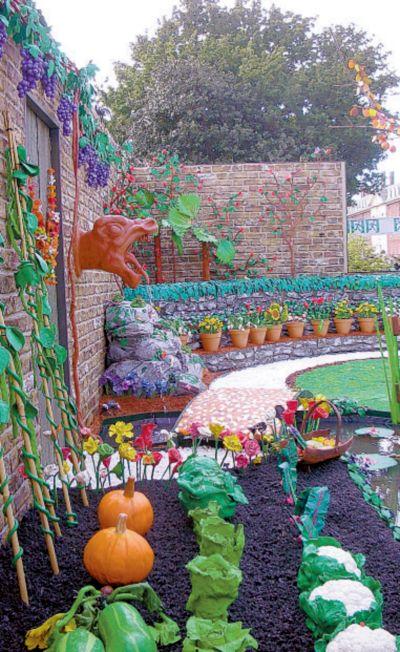

Only this summer, a two-and-a-halfton “Paradise in Plasticine” exhibit went on display at the Chelsea Flower Show.

Though it might better have been called Feat of Clay, the exhibition – fronted by Top Gear television presenter James May – may now go on permanent display.

The promoters called it sculpted art – “inspired by nature’s variety and fecundity” – the only Chelsea exhibit not to contain living plants and one of the few, it’s said, not to win a medal. It also included a bust of Harbutt and a “secretive” garden gnome.

“Plasticine,” they said, “has been extensively used to model things like little penguins in bow ties or an unconvincing, 2in high Eiffel Tower.

“It’s time for the full, expressive breadth of this modelling medium to be revealed, the largest and most complex Plasticine model ever attempted.”

In March 2009, the Tate Modern displayed 200 Plasticine figures of Morph – one wearing a bikini – in memory of television artist and presenter Tony Hart.

Then yesterday, International Animation Day, North Shields came to life. If not the dawn of a new Plasticine Age, it’s proving quite a year for William Harbutt.

HE was born in North Shields in 1844, studied at the National Art Training School in London and from 1874 to 1877 was head of the Bath School of Art.

Though none appears to know much of his Shields connection – did his mother just drift in on the tide?

Were there tangled lines of fisher folk? – it’s of little concern to John Fleet.

The memorial to the man who broke the mould will be in the form of 29 seats and 14 bins in the shopping centre, all made from brightly coloured concrete.

Though the town, like Bishop Auckland, has a statue of Stan Laurel – Laurel’s father having been manager of the North Shields’ theatre for slightly longer than he was at Bishop – few other local heroes come readily to mind.

It might also have been difficult to explain a statue of Dr Hastings Banda, the first prime minister of Malawi, who was a medic in North Shields from 1942 to 1945.

“The seats needed replacing, I looked through all the usual catalogues and was a bit underwhelmed,”

says Mr Fleet.

“We wanted something a bit quirky, perhaps a bit different. One of the council officers mentioned William Harbutt. It was good enough for me, though unfortunately we haven’t been able to find any of his descendants.”

He admits to having been more of an Airfix man – “I wasn’t bad with Plasticine, but it hadn’t the same appeal”

– and especially adept with the almost-forgotten Bayko building set.

Maggie Richardson, evangelistic president of North Shields Chamber of Trade, praises a “fabulous” idea but admits to being rather less than a dab hand with Plasticine. “The arms and the legs kept falling off, so we’d end up rolling it up into one of those multi-coloured balls.

“We’re very privileged to be part of the concept. We hoped to come up with something different and this is going to be really colourful. Even standing here in the rain, the seats really looks like Plasticine. It’s very appealing.”

HARBUTT eventually started his own art school in Bath, was 53 when he invented his non-drying modelling clay to help his students and two years older when it was awarded a trade mark.

The make-up is still officially secret.

As well as providing the new street furniture, North Tyneside Council also invited children from the area’s 16 primary schools to write something to salute the town’s formative figure.

Peter Dyers, the winner, wrote a story about a Plasticine roller coaster – the Plasta Blasta Coaster – which will be featured on six paving stones.

Other children spent International Animation Day at workshops celebrating Harbutt’s achievement.

He died from pneumonia while visiting New York in 1921. Though the original factory was destroyed by a fire in 1963, family members kept the business going until 1983. From then until 1986 it changed hands several times.

Plasticine, a testament to flexibility, is now made in Thailand.

Ten things you may never have known about Plasticine

■ The original Plasticine was grey, first selling to the public in four colours. The Chelsea Flower Show exhibit had 24 colours.

■ William Harbutt’s family promoted Plasticine as a children’s toy by producing modelling kits in association with Mr Men, Noddy and Paddington Bear.

■ The earliest space suits were modelled in Plasticine.

■ Morph made his first appearance in 1976, the first mainstream British television programme with signing for the deaf. It also introduced Sylvester McCoy, a future Dr Who.

■ A BBC website claims that Plasticine is now seen as “a mainstream material for the manufacture of Hollywood’s leading actors”.

■ It is known to produce a more lifelike result, it scurrilously adds, “than the now seriously outmoded Roger Moore”.

■ A Grand Day Out, the first Wallace and Gromit adventure – Wallace and Gromit are Plasticine personified – appeared in 1989.

■ Wallace graduated from Dogwarts University, which should not be confused with Doggarts.

That was a department store in Bishop Auckland.

■ The Italian equivalent of Plasticine is called Pongo – not to be confused with Pongo, Jack and Crabfat, that’s a military surplus store in Hetton-le-Hole.

■ Unable to award a medal to an exhibit without a single living plant, the Royal Horticultural Society awards “Paradise” a Plasticine medal instead.

…and one thing we still don’t know: what Mr and Mrs Harbutt were doing in North Shields in the first place.

THE little chapel in Wooley Terrace, among the brightest and best-loved in all Christendom, holds its last service at 2.30pm on Saturday, November 14. It will be a hugely sad day.

The At Your Service column had last visited in 2005. “It is a perfect little chapel, a film set chapel, a challenging but unchanging chapel,” we observed.

Wooley Terrace is on Stanley Hill Top, known sometimes as Stanley Crook and sometimes as Mount Pleasant. Locals rhyme “Wooley”

with duly.

It opened in 1884, the chapel at one end of Wooley Terrace, the pit at the other and 102 houses in between.

“It’s just old age, illness and lack of money,” says Brenda Worthington, though, perhaps crucially in those wind-blown parts, they’re also faced with a hefty bill to restore the heating system.

Once Stanley also had a pub, shop and post office, now all gone. The Little House on the Prairie, ideal home for Stanley United, was destroyed by arsonists. Sheep graze, doubtless safely, on the pitch.

Once there were also two chapels, the “Primitives” leading a separate existence long after Methodism’s formal unification in 1932.

The former Primitive chapel was also a second home for the Armstrong family, for Ernest who became both deputy Speaker of the House of Commons and vice-chairman of the Methodist Conference and for Hilary, who succeeded him as North-West Durham’s MP.

Hilary recalls accompanying her Auntie Ethel around the village every Good Friday, harmonium in the back of a cart and at the end a blood orange as a reward for good behaviour.

She also remembers when the village was thriving. “It’s really, really sad. Methodism was so important to this valley and to the Labour Party.

People don’t live in villages any more.”

The chapel holds a songs of praise service – a swansongs of praise, perhaps – at 10.30am this Sunday. More of that in At Your Service on November 7.

MY friend Terry Garnett – partner of Sue Carr, who has the Britannia in Darlington – died suddenly last Thursday. He was only 56.

Many knew him, and will overflow St John’s church next Tuesday.

Many more will have glanced up at the pub, just off the ring road, and admired its wonderful and awardwinning floral displays.

Officialdom talks of Britain in Bloom. Terry loved to see the Brit in Bloom and since there’s not a conventional pub garden, grew one on the roof as well.

Though he supported one or two dodgy football teams, he was a great character, an enthusiastic raconteur, a generous friend and a proud and loving family man. The place won’t be the same without him.

NOTING the passing of the Reverend David Jones, a former vicar of Staindrop, the column two weeks ago observed that among the many letters after his name – degrees and things – was the word hadji. Whatever could it mean?

An email from Mike Callaghan, Crook lad originally, answers the question but adds a mystery.

“The term refers to a male who has made the annual pilgrimage to Mecca. As the Hajj, and indeed everywhere in the holy city of Mecca, is permitted only to Muslims, there must be an interesting tale to tell.

“There are dreadful penalties for non-Muslims. Maybe he was smuggled in.”

Mike now knows about these things. He works in Saudi Arabia.

IT wouldn’t be a column, of course, without a word on the Unnamed Streak – by now perhaps the longest streak in journalistic history. We mentioned a few weeks ago that British Railways planned to call the Class W1 steam engine Pegasus but somehow never quite got round to it. Pegasus was finally affixed to a Freightliner Brush-type diesel, 47298 – a flying workhorse, if ever.

John Rusby in Bishop Auckland sends the photograph. “60700,” he inarguably supposes, “has received far more attention through never being named at all.”

…and finally, a little era ended, two weeks back Wednesday, at the Headlam Hall Hotel. The demands of six fact-based, multi-faceted columns each week mean it is no longer possible to give daytime talks. Teesdale Ladies’ Luncheon Club, a jolly lot, copped the peroration.

Headlam Hall is approximately in the middle of nowhere, a three-mile walk from the nearest bus stop. Halfway along the road, its governance changes from Darlington – absurdly “Gateway to the Tees Valley” – to County Durham, “Land of the Prince Bishops”.

The Durham scaffies, for it was bins day, got as far as the county boundary and remembering all that’s said about dust to dust, turned around and retreated whence they’d came.

So the lunching ladies were smashing, from the youngster who’d been Middleton-in-Teesdale carnival queen in 1963 – crowned, she recalled, by Tom Coyne – to the lady who’d briefly taught at Timothy Hackworth infants in the days I was on the receiving end there and thought Miss Vint, the head, every bit as fearful as the poor bairns did.

The cheque, unsolicited, has gone to Oxfam. The treasurer, pure coincidence, worked at the Oxfam shop. It was a happy ending.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article