Officially redundant, though not a lost cause, Stanwick St John church rises to the occasion for a fine service.

JUDE is the patron saint of lost causes, and of hopeless cases. He is also patron of the Chicago police department (for reasons which may not need explanation), of a football team in Rio de Janeiro (ditto) and of ibises, for reasons which cannot be imagined for a moment.

“When I was a kid in Liverpool, the evening paper used to be full of prayers from people invoking Jude,”

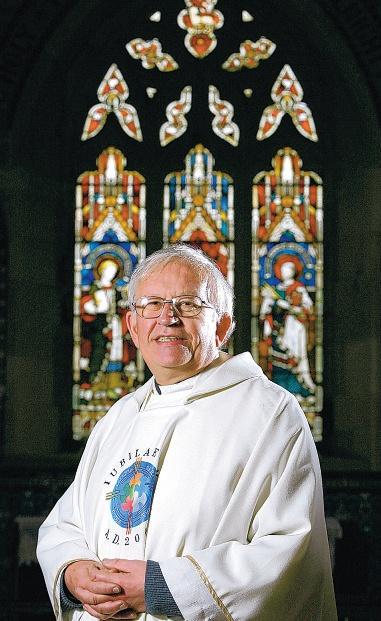

recalls the Reverend Stan Haworth, Rector of the Forcett group of parishes, north of Richmond.

It would thus be easy to suppose that Hey Jude, the seven-minute Beatles track that in 1968 became Britain’s longest-ever No 1 hit, was itself a plea – a Mersey mission – to the saint.

The supposition would be mistaken.

Paul McCartney wrote Hey Jude, originally Hey Jules, in a bid to comfort John Lennon’s son, Julian, after Lennon’s liaison with Yoko Ono became the news of the world.

Those who thought it might have been written for them included the actress Jane Asher, once the love of McCartney’s life, and some bird on the Daily Express.

All this talk of the patron saint of lost causes arose before last Sunday’s service. That Andy Murray was simultaneously trying to win his first tennis Grand Slam event – and one down, it was whispered, already – was wholly coincidental.

That Mr Haworth is an Everton fan and that they were to meet the glorious Arsenal two days later was also of little relevance, though Everton duly did an Andy Murray.

MR Haworth, a very nice man, had been priest-in-charge of the six churches in his rural benefice since the foot-and-mouth days of 2001.

Last month he was made rector, one of the last incumbents in the Church of England to be given parson’s freehold, which legally ended this week.

Practically, it makes little difference.

Technically, it means that in order to shift him he has to be declared bankrupt, a lunatic or found guilty of conduct unbecoming a clerk in holy orders.

Since there’s not much fear of any of those – though he’s a bit worried about his central heating bill – he continues pretty much as before, though the formal institution featured something of a lost cause, too.

Janet Henderson, the archdeacon of Richmond, had taken a wrong turn in Aldbrough St John, ending up stuck at the bottom of an icy bank on a narrow country road.

Stan went off on a rescue mission, the service starting 45 minutes late, the new rector required to ring the bell once for every year he expected to stay.

“I’m still ringing,” he said.

AMONG his churches is Stanwick St John, an ancient place occupied 2,000 years by Cartimandua, queen of the Brigantes.

Officially redundant, the church is in the care of the Churches Conservancy Trust with “occasional”

services for the whole benefice still held on the fifth Sunday – in this case Candlemas, known sometimes as the Presentation of Christ.

It’s a lovely old church with many tales to tell, none more extraordinary than the connection with the mighty Smithsonian Institution in Washington.

The Smithsons had Stanwick Hall, built in 1668. In 1750, however, Sir Hugo Smithson married Elizabeth Seymour, heir to the Percy family fortunes. He changed his name to that of his wife and, soon afterwards, became first Duke of Northumberland.

James Smithson was the son of Hugo’s mistress – another mistress – born in Paris in 1764. He made his fortune, bequeathed it to the US – a country he’d never even visited – to create an establishment “for the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men”.

The word at Stanwick – and, it’s said, among the Percys – is that James, illegitimate and unacknowledged, vowed that the name of Smithson should be remembered long after the Percys had been forgotten.

His fortune amounted to 104,960 gold sovereigns, canny money, the Smithsonian now the biggest museum complex in the world. The Percys haven’t done badly, either.

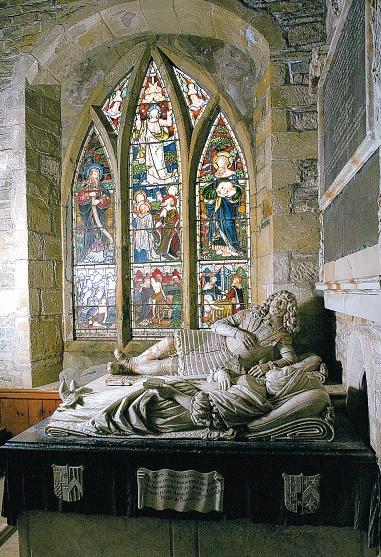

STANWICK church is home to the tomb of the first Sir Hugo, the man who in the mid-17th Century bought the estate for £4,000 and the baronetcy – cash for honours, even then – for about a quarter the price.

His recumbent figure is clad as a cavalier – “a cumbrous piece of imposture,”

says Plantagenet-Harrison’s 1897 History of Yorkshire.

Smithson was a “haberdasher of humble birth” who made his fortune in business and decided, as it were, to cut his coat according to his cloth.

The historian’s disapproval may also have been incurred because tombs of the Pigot family, long at Stanwick, had been displaced to make way for the Smithsons.

“I suppose that the flags above his tomb were made out of the old man’s shop,” adds Plantagenet-Harrison, dismissively.

Mind, there are those around Stanwick St John who suppose Plantagenet- Harrison a bit embroidered, too. Probably, they say, his first name was Fred.

WE’D last attended one of Stanwick’s occasional treats in 2005, the column obliged to observe that the first two hymns had been “unrelentingly obscure”.

Stan remembered it. It’s where all the stuff about Jude the Obscure began though that, of course, was a novel by Thomas Hardy and nothing to do with the apostle of the same name – though the biblical life’s pretty hazy, too.

These weren’t obscure in the least.

We began with Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken – churlish in the extreme to suggest that it was the “wrong” tune – followed by Love Divine All Loves Excelling and by Lead Us Heavenly Father Lead Us.

Stan preached a good sermon on communication and on the peculiarities of the English language – “ough” capable of being pronounced eight different ways – the choir was in good voice, prayers led by Doreen Liston, the reader.

Maybe 40 were present, none hurrying back to watch the Australian Open, perhaps in the knowledge that some cases are beyond hope.

Still, rarely may so much wayward information have been herded into the safekeeping of one At Your Service column. All may not be lost, after all.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article