The theme is agricultural as parishioners plough on with a tradition – and turn their swords on a bishop.

IT was Plough Sunday, the time of year when farm workers traditionally returned to the straight and narrow after the Christmas merriment and when church folk gave thanks for harvests past and prayed for fruits to come.

The column has covered quite a few over the past 15 years, on one occasion writing the headline “Furrowed lang syne” of which I remain absurdly and immodestly proud.

Last week, so great the Church’s desire to be relevant, they held a Plough Sunday service in London to which people were asked to bring for blessing their mobile phones, laptops, iPods and Blackberries.

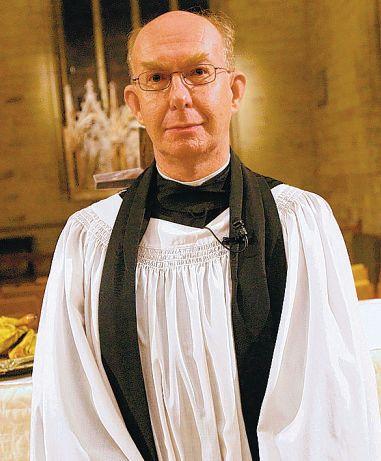

Happily, however, there are those who still believe that blackberries are something with which to make jam. We joined them, and a slightly apprehensive James Bell, Bishop of Knaresborough, for last Sunday evening’s plough service at Masham.

Masham’s in North Yorkshire, brewing country, roughly between Bedale and Ripon. The celebrated Old Peculier ale takes its name from the ecclesiastical parish’s historic status as semi-independent of the Archbishop of York.

It was the parish which was a “peculiar”, it should be added, and not some scatty archbishop, though doubtless there’ve been one or two of those.

A church has stood at the end of Masham’s expansive square for more than 1,000 years, St Mary’s a magnificent building magnificently illuminated, the churchyard – in daylight – full of interest, too.

Gravestones include that of Julius Caesar Ibbotson, 200 years ago a wellknown artist, Philip Cunliffe-Lister, 1st Earl of Swinton and senior government minister, and George Thornberry, a bell ringer who died in 1810.

Here lies an old ringer Beneath this cold clay, Who hath rung many peals Both to serious and gay.

Thro’ grand sires and triples With ease he could range, till DEATH called his bobb And brought round his last change.

The plough service has been held for longer than any can remember, but was suspended during the Second World War. When resumed in 1946, the North Home Service was there to record the great occasion.

“We were just young girls, but I can still remember all those men running round with cables,” recalls Margaret Nesom.

The format may have changed little.

The ancient plough, now kept at the back with the churchwardens, is carried forward by four of the sturdier locals to be blessed, alongside a milk churn and a fleece.

The service is agriculturally themed. The plough, sped, is returned whence it came. At the end there are longsword dancers. It is the reason for the bishop’s apprehension.

AMONG the more unusual aspects of the service is that the lady of this house is present, having met the Bishop of Knaresborough at a social function two evenings previously and been persuaded that it was better than waiting outside in the car for two hours.

The longsword team may also be a reason for her attendance. She is helplessly smitten by the Kingsmen, a Newcastle-based team of dashing blades and rare agility who even turn somersaults – or cowp their creels, as is the preferred term in those parts – whilst risking life and limb.

One or two of the Highside longsword dancers may be of riper years. Put it this way: if a sword does them an inadvertent mischief, they may not be cut off in their prime.

“I bet they don’t do somersaults,”

she says.

It’s a clear, crisp evening, the moon almost harvest-like, the folk of St Mary’s warmly welcoming.

We sing We Plough the Fields and Scatter, a line in the second verse changed from “The wind and waves obey him” to “He fills the earth with beauty”, perhaps on the grounds that it is more obviously true.

Bishop James takes as his sermon theme a familiar verse from Micah – “They shall beat their swords into ploughshares and their spears into pruning hooks”.

Brought up to date, he says, it might translate as turning tanks into tractors and helicopters into harvesters – “the means of destruction are converted into the means of production.”

He’s done his homework, it’s a very good sermon. The bishop even quotes a recent Government food sourcing report – “better on analysis than strategy”. It’s also pretty strong on jargon – “Whitehall waffle” as David Cleeves, Masham’s vicar, puts it.

Farming’s now tough love, of course. Farmers no longer cry wolf.

We pray for those who are close to bankruptcy, those who want to retire but can’t, for farming families in distress and for greater returns, too.

David Nesom, Margaret’s son, says that things are probably a bit better than they were during the foot and mouth outbreak, talks of how they’re hamstrung by so many rules and regulations, is pleased they’ve survived the snows.

“Some people say it’s killed all the bugs. I don’t know about that, but it nearly killed all us off, it was so cold.”

David Cleeves says afterwards that he doubts if many town dwellers understand the rigours of farming. “To be honest, most of them haven’t the slightest idea of how their food gets from the field to the supermarket.”

At the end there’s the dance, wonderfully intricate, performed with extraordinary energy and much skill. Though they don’t cowp their creels, the possibility is so great that the photographer’s on his knees. It’s not every day you see a photographer on his knees in church.

It’s the custom, they say, to behead a “worthy” when the dance ends.

Few may be worthier than the Bishop of Knaresborough.

The swords are pulled from his throat at the last minute. “I wasn’t worried for a moment,” says Bishop James. Nor I; hand to the plough service, it’s been a memorable evening.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereComments are closed on this article