Going halfway to somewhere, Chris Lloyd stumbles upon a bare knuckle, prize-fighting, Derby-winning MP who was rescued from a debtors’ prison to sink some of Durham’s largest collieries.

THORNLEY feels like it is in the middle of nowhere, but has it ever been halfway from anywhere?

It is a sprawling former pit village, somewhere between Durham City and Peterlee.

You can tell where it is because a sign on the A181 points to it.

But that sign also points to the Crossways Hotel, which is not there at all.

The hotel, formerly known as the Halfway House, was demolished in the summer, leaving only a vague outline as a memory of where one of Durham’s first – perhaps its very first – miners’ union meeting was held.

Pre-coal, Thornley was “a wild and thinly populated area”, traversed by pilgrims travelling from the shrine of St Hild, in Hartlepool, to that of St Cuthbert, in Durham City. Indeed, the bank the A181 rises over to the west of the village is still known as Signing Hill. Here, pilgrims caught their first glimpse of Durham Cathedral and made the sign of the cross.

Pre-coal, Thornley’s population hovered agriculturally about the 50 mark.

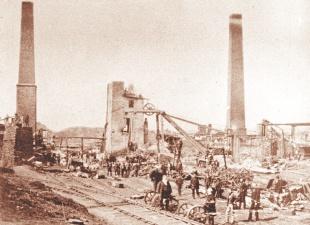

Then came coal. It was discovered on January 29, 1834, 80ft down in the Five Quarter seam. By the time of the 1841 census, Thornley’s population had exploded to 2,730 – all sucked in by the coal to create a wild community living in wild conditions.

The first to arrive were the shaft-sinkers – specialists from Cornwall and Germany.

They were followed by colliery labourers, from Ireland.

Their first homes were built of boulders, had soil floors and were barely furnished. The pubs were open from 6am to 11pm, which lubricated local conflicts. It is said that, for much of the 19th Century, the Irish Catholic community walked down one side of the street while the English Protestant and non-conformist tradition trudged down the other.

They worked in wild conditions, too. On August 5, 1841, an explosion in the Harvey seam killed nine workers. One was 42-year-old Thomas Haswell, who left a wife and seven children.

The other eight victims were boys aged between nine and 17.

The inquiry blamed the disaster on the youngest of them all, Robert Gardner. He was a trapper, in charge of opening and shutting a ventilation door, or trap.

Earlier on the fateful day, which also killed his 17-yearold brother, John, Robert had been cautioned for leaving his door open. Then, decided the inquiry, Robert had fallen asleep with his door shut. Without ventilation, foul air had built up in the tunnel.

When he awoke alone in the pitch darkness, he lit his candle to see what was going on, and the whole lot went bang.

The following year, the Mines Act prohibited children from working more than ten hours a day down below, so poor Robert could have been manning his door for 18 hours without a break.

His day could have started at 2am, meaning he would only have seen sunlight on a Sunday, and he would not have received more than five pennies pay a day. Some life.

Such conditions encouraged miners to club together to demand improvements. Their early unions were fractious affairs, and the mineowners held the whip hand. If men went on strike, replacements were brought in from other regions, and the men and their families were turfed out of their homes.

On November 24, 1843, warrants were issued for the arrest of 68 Thornley miners, who were absent from the pit without leave. They were on strike. They were found guilty at Durham and imprisoned for up to three months.

Over the next couple of decades, the union grew in strength, and on September 23, 1869, the Durham miners held their inaugural delegate meeting on a field beside the Halfway House pub, in Thornley.

This could be considered to be the first meeting of the Durham Miners’ Association (an honour usually given to a meeting held on November 20, 1869, in the Market Hotel, Durham); this could even be the first miners’ gala (an honour usually given to the gathering in Wharton Park, Durham, on August 12, 1871).

Whatever its exact place in mining history, it was clearly a significant meeting.

Thornley was chosen as the venue because it was one of the largest and most politicised collieries – within a year, its lodge would have 230 members and be the biggest in the county.

It also had one of the leading lights in the movement. The first secretary of was a chap called A Cairns.

He appears to have acted extremely bravely during the 1841 disaster at Thornley, and he was its chosen delegate to represent it at that inaugural meeting on the field beside the pub that is no longer there.

KEN Orton, of Ferryhill Station, County Durham, alerted Echo Memories to the demise of the Halfway House, which in the Seventies was redeveloped as the Crossways Hotel.

“I have often wondered about that pub,” says Ken, who spent the first 27 years of his life in Thornley. “I remember what it was like over 40 years ago. It had its old name The Barrel and Grapes Inn inscribed high on its whitewashed wall, and it still served beer straight from a barrel on the bar.

“The point I never understood is where is the Halfway House halfway between. People said it was halfway between Durham and Hartlepool, but if you look at a map, it isn’t.

“Can anybody help?”

THORNLEY Colliery was sunk in 1834 by John Gully and Partners. Those partners included Thomas Wood, of Coxhoe Hall, Durham lawyer John Burrell and Sir William Chaytor, of Witton Castle, near Bishop Auckland, and Clervaux Castle, near Crofton- Tees. Sir William was the Whig MP for Durham City and then Sunderland in the 1830s, although he must have been a scruffy fellow because he was known locally as “Tatty Willie”.

But the partnership was headed by John Gully, one of the finest characters ever to grace this page.

He was born in Gloucestershire, in 1783. His father was an innkeeper who became a butcher in Bristol, and then died leaving young John to run the business.

Appropriately for a novice butcher, he fell deeply into the red and in 1805 was imprisoned in the King’s Bench Prison for Debtors in London.

John was “a fine, strong young man, over six feet high, with rather an open and ingenuous countenance, rather an innocent tip-tilted nose and beautiful hands of which he was all his life extremely proud”.

He also had a reputation for being rather useful with those hands. In jail, he received a visit from Henry “the Game Chicken” Pearce, the champion bare-knuckle fighter of England. They sparred, and the Game Chicken realised that Gully would be a worthy opponent, if he were free.

The Fancy became involved. The Fancy was a group of aristocratic prize fight enthusiasts. It paid off Gully’s debts, released him from prison, and put him into training.

The fight was in Hailsham, Sussex, on October 13, 1805, before a large crowd drawn from all classes. The Duke of Clarence, later King William IV, rode from Brighton to see it. Bare knuckled and footed, it lasted 64 rounds – one hour and 17 minutes – before Gully failed to come up to scratch. The Game Chicken gamely retained his title and told John: “You are a good fellow. You are the only man who has ever stood up to me.”

Soon the Chicken retired.

Gully was matched against Bob “the Lancashire Giant”

Gregson, who came from Lancashire and was fairly tall.

They fought “a terrific maul” in Newmarket, on October 14, 1807, over 36 rounds after which Gully was declared the champion.

He won the rematch in Hertfordshire the following May, in front of a crowd so large that locals thought the French had invaded and called out the Volunteers to see them off.

From the ringside, Gully announced his retirement.

He became a pub landlord in London, and developed an astute eye for a horse. He became the Prince of Wales’ principal betting agent, and in 1829, Gully heavily backed his own horse Mameluke to win the Derby.

When it failed, he graciously paid out £40,000.

Still he was in the money.

For some reason in the 1820s, he had acquired shares in Hetton colliery, one of the earliest collieries in the Durham coalfield.

In 1832, Gully bought the Ackworth estate near Pontefract, entered Parliament as a Liberal MP and won £85,000 backing the winners of the Derby and the St Leger.

It must have been this money that he used the following year to pull together the partnership that sank Thornley Colliery, and in 1840, he invested in the sinking of nearby Trimdon Colliery.

In 1846, his horse, Pyrrhus the First, won the Derby, a feat repeated by Andover in 1854. Gully also owned the winners of the 1846 Oaks and the 1854 2,000 Guineas.

In 1862, Gully bought Wingate Grange Colliery and lived at Cocken Hall, which stood near Finchale.

But old age forced him to move into 7 North Bailey, in the centre of Durham, where he died on March 9, 1863.

He left two wives, each of whom had presented him with 12 children.

And in death, he had one last wonderful eccentricity.

When his favourite daughter had died, she had been buried by the wall of the Protestant churchyard, in Ackworth. Gully had asked the vicar if he could be buried alongside her.

But Gully was a Catholic, and the vicar refused to allow a left-footer in his churchyard.

So Gully bought the land outside the churchyard wall, had it consecrated by a Catholic priest and when the time came he was laid to rest beside his beloved daughter.

When you are six feet under, the surface foundations of a wall and pig-headedness of a vicar do not form much of a barrier.

Chris Lloyd is keeping Echo editor Peter Barron company at a book-signing session on Sunday at Head of Steam, formerly Darlington’s North Road railway museum.

Between 2pm and 4pm, Peter is signing copies of his Dad at Large 4: The View From The Doghouse, while Chris will be signing Of Fish and Actors: 100 Years of Darlington Civic Theatre, and A Walk in the Park: the Story of Darlington’s South Park. These are books number four and five in the series taken from this column. The signing is part of the Santa at the Station event.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here