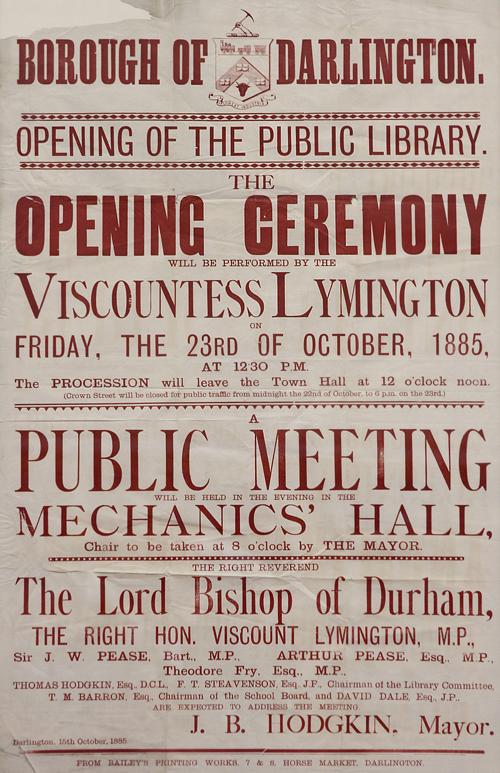

THOUSANDS of people lined the streets of Darlington 125 years ago to witness an ornate silver key being turned in the new library door by a young lady. They thought they were witnessing history. After all, the free library had been a controversial ambition of many townspeople for years, as Echo Memories told.

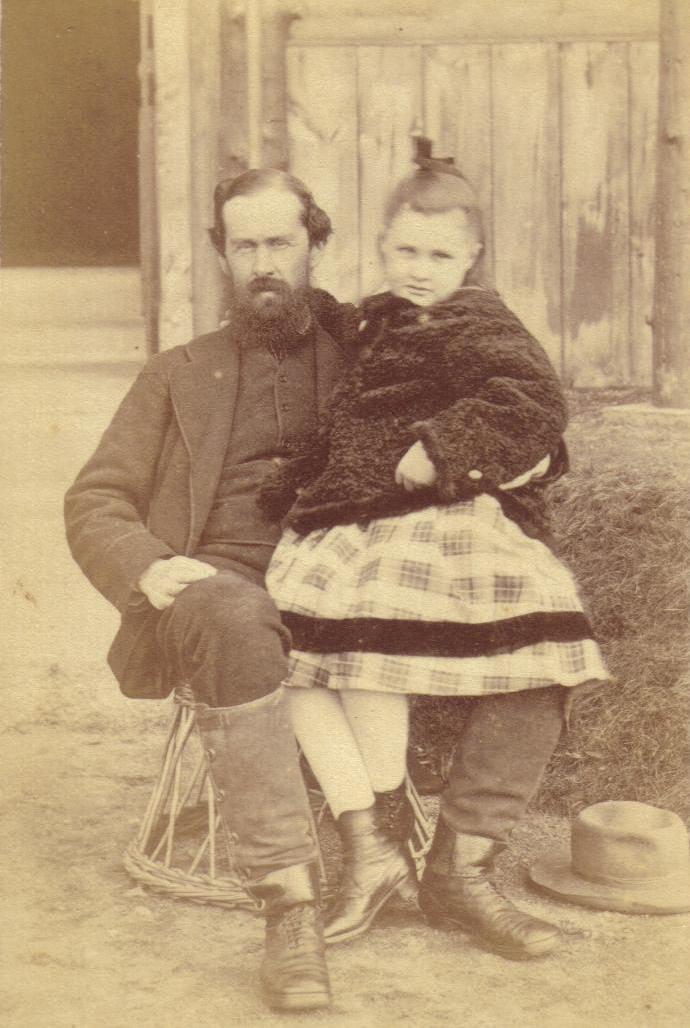

THE library was named after Edward Pease, the father of the 19-yearold Beatrice, who had the silver key in her hand.

He had died at the age of 46, leaving her an orphan to be brought up by her uncle, Sir Joseph Whitwell Pease.

Indeed, on that historic opening day of October 23, 1885, Sir Joseph – from 1865 until his death in 1903, the MP for South Durham – made a speech from the platform erected outside the Edward Pease Free Library.

So too did Beatrice’s new husband, Lord Lymington, who was also a Liberal MP representing a constituency in his native Hampshire.

What the “immense concourse of people” milling around the platform cannot have realised at the time was that beyond the opening of the library, the real history they were witnessing was the first appearance of the golddigger who would ruin the Pease dynasty.

But first the library opening. Beatrice, the guest of honour was “greeted by an outburst of cheering” as she turned the silver key in the lock of an impressive building constructed on top of her family’s old mill dam by the town’s most famous architect, GG Hoskins.

Today, we rush past the library without time to look up at the fine carvings above the door. They show the Pease coat-of-arms next to that of the borough, with a wise old owl in front with an open book in its claw.

Having turned the key, Beatrice – Lady Lymington – stepped inside for a quick tour, then returned to the platform to pronounce herself happy.

“It gives me greatest pleasure to be here today and to declare this building open (Applause),” she said. “It was, as you know, bequeathed to you by my dear father, and I feel sure that his trustees, my uncles, have fulfilled his bequest entirely as he would have wished. (Loud cheers)”

No one disagreed. The Conservative- supporting North Star said: “No public library in England is more perfect as regards its general arrangements and comfort of facilities.”

She was followed by a few other speeches before everyone adjourned to the Trevelyan Hotel on the corner of Blackwellgate and Grange Road for luncheon and yet more speeches. It was followed by an evening meeting at the Mechanics Institute, where there were even more speeches, which so many people wanted to hear that there was an overflow meeting over the road in the Friends Meeting House.

Whenever Lord Lymington rose to speak, he was, according to the Echo, greeted with “an outburst of cheering”.

Indeed, Sir Joseph was extremely generous in introducing him. He explained how, on the death of his brother, Edward, in 1880, 14-year-old Beatrice had gone to live with him at his enormous mansion of Hutton Hall, near Guisborough.

He said: “She came under my roof as a child, and to my wife and myself, she has been as a daughter. Now she had found other realms of love, and I am sure that those of my fellow townsmen who have seen and heard Lord Lymington will feel that her affections have been put upon a man worthy of her choice.

“I assure Lord Lymington that both for your wife’s sake, her father’s sake and for your own sake, you will ever find a welcome in this town where you have made your his first appearance this day.”

In private, even as he stood on that platform outside the library, Sir Joseph must have been having profound doubts about the addition to his family.

Lymington was christened Newton Wallop and he was the heir to the Earldom of Portsmouth. He’d become acquainted with Sir Joseph’s son, Jack, at Cambridge University, and his lordship gained a huntin’ and shootin’ invitation to Hutton Hall.

Initially, Lord Lymington formed a liaison with Sir Joseph’s daughter, Maud, but when Jack told him that she was not “the heiress”, Mr Wallop found himself whacked in the eye by the hitherto unobserved charms of Beatrice.

They became engaged in November 1884. She was 18; he was 28.

Within two weeks, Beatrice and her beloved had taken legal advice about her inheritance.

Sir Joseph replied that her father had died with whopping debts of £176,833 – £16.8m today.

On paper, Edward’s debts were more than covered by his shares in the family’s industrial concerns in the Tees Valley.

But, cautioned Sir Joseph, it was not worth cashing them in during the depths of a recession.

In reality, his brother’s estate was in such a mess that the Peases couldn’t really afford the £10,000 Edward had stipulated should be used to open the library.

So that was the background to those happy family scenes at the opening of the Edward Pease Memorial Library 125 years ago as Sir Joseph introduced to the cheering crowds a man he described in his private diary as a “fortune hunter” who had “a decided notion about the main chance”.

It got worse. In 1893, Beatrice and Newton Wallop – now the Earl and Countess of Portsmouth – hired a hardnosed London solicitor, Sir Richard Nicholson, to extract her inheritance from Sir Joseph.

Pease versus Portsmouth reached the High Court in London in 1896. Sir Joseph maintained that now was a bad time to sell her shares and so, under intense pressure, he made a “fair and reasonable”

offer to buy her out for £223,000 (about £22m today), which was 33 per cent lower than the paper value.

Given Sir Joseph’s reputation as a Quaker gentleman of immense standing, the judge accepted the offer.

What Sir Joseph was unable to tell him, for fear of the banks foreclosing on him, was that the Peases were so stretched that the only way they could pay off the Portsmouths was by floating their company on the Stock Market.

The Portsmouths received every penny they were owed in September 1898. Two weeks later, after much agonising, Sir Joseph issued shares in Pease and Partners.

It coincided with a change in industrial fortunes. The price of Durham coal was rising faster than at any time in the previous 30 years. Buyers were so excited by this prestigious company coming to market at such an opportune time that there were 12 times as many applications as there were shares. And so the price rocketed...

As soon as the Portsmouths heard, they went straight back to the High Court demanding a recalculation of the settlement.

Portsmouth versus Pease was heard this time by Mr Justice Farwell. Given events on the Stock Market, he concluded that each of Beatrice’s shares was worth 25 shillings, but Sir Joseph had only paid her 13s 4d.

Therefore, he calculated, Beatrice’s settlement should really have been £302,000, and not the £223,000 that Sir Joseph had deemed “fair and reasonable”.

Worse than that, Mr Justice Farwell said Sir Joseph had made three false statements to the court and labelled him “an unsatisfactory witness”.

Aged 72, Sir Joseph was a broken man. Barclays was called in and, after auditing the books, discovered that a major part of the Peases’ business was, in fact, insolvent.

Sir Joseph was forced into a firesale of all his family’s assets, including Hutton Hall, and was only saved from personal bankruptcy by the generosity of his Quaker friends, who did a whip-round to keep out the wolves that were howling at the door.

Far worse for this kindly Quaker gentleman than any of these financial indignities was that his reputation had been thoroughly traduced by the highest court in the land.

He died on his 75th birthday in 1903 at Falmouth on the South Coast, still estranged from Beatrice, the orphan heiress he had brought up as his own.

His deep bitterness can be felt in this extract from his diary for December 31, 1901: “We wound up the law suit with Lord and Lady Portsmouth in which we all felt we were most iniquitously robbed...

“After having found her a home till marriage... after having held on to her colliery property and done all I could through all the bad times of the coal trade... they charged us with fraud... and (my brother) Arthur’s estate and mine were defrauded...

“Such is gratitude and love.”

■ With many thanks to Katherine Williamson and Mandy Fay at Darlington library.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here